TY 5 LI

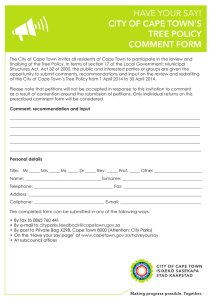

advertisement