Methodology to value the natural and environmental resources of

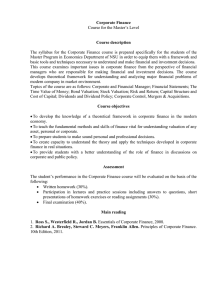

advertisement