Document 10392500

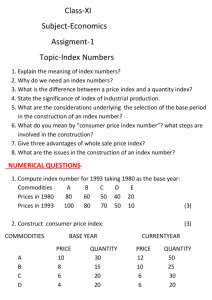

advertisement