Core Academic Skills for Educators: Writing Praxis

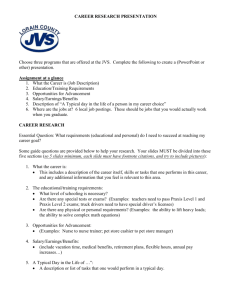

advertisement