National Urban Renewal Programme Lessons Learnt

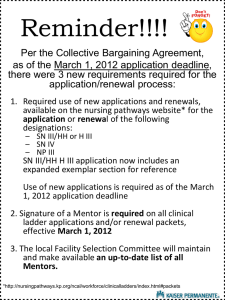

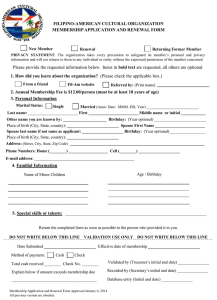

advertisement