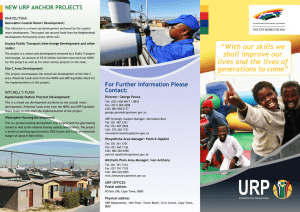

National Urban Renewal Programme Implementation framework

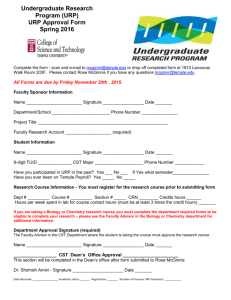

advertisement