THE PROCEEDINGS The South Carolina Historical Association 2004

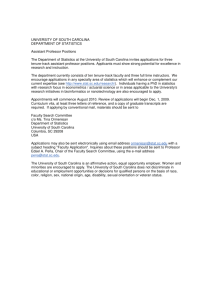

advertisement