Trend Report | Part 1 Towards Basic Justice Care for Everyone

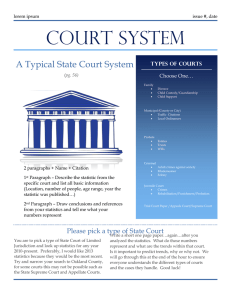

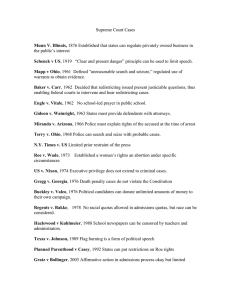

advertisement