doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2005.09.021

J. Mol. Biol. (2005) 353, 990–1000

Cofilin Increases the Torsional Flexibility and Dynamics

of Actin Filaments

Ewa Prochniewicz1, Neal Janson2, David D. Thomas1 and

Enrique M. De La Cruz2*

1

Department of Biochemistry

Molecular Biology and

Biophysics, University of

Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN

55455, USA

2

Department of Molecular

Biophysics & Biochemistry

Yale University, New Haven

CT 06520, USA

We have measured the effects of cofilin on the conformation and dynamics

of actin filaments labeled at Cys374 with erythrosin-iodoacetemide (ErIA),

using time-resolved phosphorescence anisotropy (TPA). Cofilin quenches

the phosphorescence intensity of actin-bound ErIA, indicating that binding

changes the local environment of the probe. The cofilin concentrationdependence of the phosphorescence intensity is sigmoidal, consistent with

cooperative actin filament binding. Model-independent analysis of the

anisotropies indicates that cofilin increases the rates of the microsecond

rotational motions of actin. In contrast to the reduction in phosphorescence

intensity, the changes in the rates of rotational motions display non-nearestneighbor cooperative interactions and saturate at substoichiometric cofilin

binding densities. Detailed analysis of the TPA decays indicates that cofilin

decreases the torsional rigidity (C) of actin, increasing the thermally driven

root-mean-square torsional angle between adjacent filament subunits from

w48 (CZ2.30!10K27 Nm2 radianK1) to w178 (CZ0.13!10K27 Nm2

radianK1) at 25 8C. We favor a mechanism in which cofilin binding shifts

the equilibrium between thermal ErIA-actin filament conformers, and

facilitates two distinct structural changes in actin. One is local in nature,

which affects the structure of actin’s C terminus and is likely to mediate

nearest-neighbor cooperative binding and filament severing. The second is

a change in the internal dynamics of actin, which displays non-nearestneighbor cooperativity and increases the torsional flexibility of filaments.

The long-range effects of cofilin on the torsional dynamics of actin may

accelerate Pi release from filaments and modulate interactions with other

regulatory actin filament binding proteins.

q 2005 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

*Corresponding author

Keywords: cofilin; actin; cooperativity; anisotropy; torsional rigidity

Introduction

Members of the ADF/cofilin family of actinbinding proteins sever actin filaments1–3 and may

accelerate subunit dissociation from the pointed-

ends.4 Severing and enhanced depolymerization

are likely to arise from cofilin-mediated changes in

actin filament structure. ADF/cofilin binding

changes the average twist and subunit tilt of a

filament,5,6 increases the disorder of subdomain 27

Abbreviations used: TPA, transient phosphorescence anisotropy; ErIA, erythrosine iodoacetamide; t, triplet excitedstate lifetime of ErIA; I, phosphorescence emission intensity; Ivv, vertically polarized component of the phosphorescence

emission; Ivh, horizontally polarized component of the phosphorescence emission; A, amplitude; G, instrument

correction factor; R, anisotropy; r0, initial anisotropy; rN, final anisotropy; f, rotational correlation time; qa, angle

between the absorption dipole of bound ErIA and the filament axis; qe, angle between the emission dipole of bound ErIA

and the filament axis; hDxi, rms average fluctuation of the torsion angle between adjacent filament subunits; li, filament

length distribution; k, amplitude reduction factor; a, actin filament radius; h, long-axis height of an individual actin

filament subunit; C, torsional rigidity; a, torsional spring constant; g, rotational frictional coefficient; Dk, rotational

diffusion coefficient; kB, Boltzmann’s constant; h, solvent viscosity.

E-mail address of the corresponding author:

enrique.delacruz@yale.edu

0022-2836/$ - see front matter q 2005 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

991

Cofilin Affects Actin Filament Torsional Dynamics

and the DNase-binding loop,8 disrupts the interface

between subdomains 1 and 2 along the long-pitch

helix of filaments9 and weakens stabilizing lateral

contacts in the filament.10,11 The change in filament

twist is propagated along the filament to actin

subunits without bound cofilin.6,7

Cofilin binding to actin filaments is cooperative5

and can be described by a nearest-neighbor

cooperative binding model.12 Cooperative interactions may be mediated through conformational

rearrangement of subdomain 2 of actin,12 which

facilitates local changes in subunit tilt observed by

electron microscopy.7

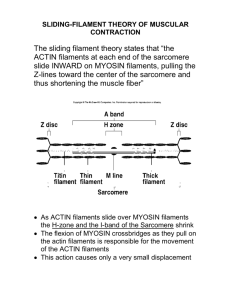

Actin filaments display two types of large-scale

movements: long-axis (flexural) bending and longaxis (torsional) twisting (Figure 1). Bending and

twisting depend on the bound nucleotide and

cation,13,14 interactions with actin-binding proteins,13–16 and actin isoforms.17,18 The flexural

rigidity of actin filaments is larger than the torsional

rigidity so filaments twist more easily than they

bend.

The cofilin-induced change in average filament

twist5,6 may modulate the mechanical properties of

actin filaments. We are testing this hypothesis using

transient phosphorescence anisotropy (TPA). TPA

of erythrosin-labeled actin has been successfully

applied to describe the microsecond timescale

dynamics of actin filaments and structural changes

in the region of actin’s C terminus.15,16,18–22 We have

previously shown that (1) TPA of actin cannot be

accounted for by rigid body rotations, but reflects

primarily intra-filament torsional motions that can

be explained in terms of the torsional twist

model, and (2) changes in the phosphorescence

intensity monitor local conformational changes in

actin.15,16,18–20 Here, we demonstrate that cofilin

binding increases the microsecond dynamics and

the torsional flexibility of actin filaments, and that

these effects can propagate to vacant sites on the

filament.

Figure 1. Conformational dynamics of actin filaments.

Schematic representation of actin filament thermal

motions.

Results

Effect of cofilin on time-resolved phosphorescence intensity decays of actin filaments

The phosphorescence intensity decays of

erythrosine iodoacetamide (ErIA)-actin filaments

(Figure 2) were analyzed by fitting data to a sum of

two exponentials (equation (3)) with amplitudes I1

and I2, and the corresponding lifetimes, t1 and t2.

The observed phosphorescence intensity decay is

dominated (I1 w0.8) by a long lifetime (t1Z

w220 ms) component, with a small contribution (I2

w0.2) from a shorter lifetime (t2Zw30 ms, “intermediate”) component. The multiple components

contributing to the decay imply that there exist

multiple (at least two) actin conformations with

microsecond lifetimes. The amplitudes and lifetimes of both the long (t1) and intermediate (t2)

lifetime components are reduced in a cofilin

concentration-dependent manner (i.e. both intensity decays are more rapid with bound cofilin; data

not shown). There is also a rapidly decaying

component (t/4 ms, short lifetime) in the presence

of cofilin, as indicated by the reduction in initial

phosphorescence intensities (Figure 2, inset). We

refer to the amplitude of this rapidly decaying

phase as I3 and the lifetime as t3.

Cofilin binding increases the population of short

(t3) and the intermediate (t2) lifetime components,

and reduces the population of the long lifetime (t1)

species (Figure 3). The mole fractional distribution

of these three components depends sigmoidally on

the cofilin concentration, consistent with cooperative cofilin binding to actin filaments.5,9,12 The

reciprocal partitioning of the short and long lifetime

components (X1 and X2; Figure 3) suggests that

these two states are in equilibrium, and that cofilin

binding shifts the equilibrium distribution of these

two states. Detailed balance requires that if cofilin

shifts the equilibrium between two conformations,

it must bind preferentially to one of the two.

Although equilibrium cofilin binding to actin

filaments is well-described by a nearest-neighbor

Figure 2. Effect of cofilin on the time-resolved

phosphorescence intensity decays of ErIA-actin filaments.

The [ErIA-actin] is 1.8 mM and the [cofilin] are: 0 (black),

0.3 (royal blue), 0.8 (red), 1.0 (green), 1.5 (violet), 2.0

(orange), and 6.0 (light blue) mM. The inset shows the

same data with the time axis plotted on a log scale.

992

Cofilin Affects Actin Filament Torsional Dynamics

anisotropy arise from the modulation of internal

microsecond filament dynamics.

Model-independent analysis: sum of exponentials

Figure 3. Cofilin concentration-dependence of the

observed intensity decay mole fractions (X). (a) Mole

fractions of the slow (X1), intermediate (X2) and fast (X3)

decays contributing to the phosphorescence decays.

(b) Inset of data in (a) to show the fast decaying

component. The continuous lines are drawn for clarity

and have no physical significance.

The effect of cofilin on actin dynamics was first

analyzed in terms of a model-independent fit of the

anisotropy decays to the sum (nZ2) of exponentials

(equation (5)) to obtain the rotational correlation

times (fi), the initial anisotropy (r0) and the final

anisotropy (rN). The correlation times (fi; i.e.

reciprocal rate constants) characterize the rates of

rotational motions, the initial phosphorescence

anisotropy (r0) characterizes the amplitude of local

sub-microsecond motions of the dye and/or

cysteine 374 relative to actin (a lower value means

more mobile), and the final anisotropy (r N)

characterizes the angular amplitudes of microsecond timescale filament motions (i.e. global

motions).

The initial phosphorescence anisotropy of actinbound ErIA (r0Z0.105) is significantly lower than

that of immobilized ErIA (r0Z0.20519) due to fast,

submicrosecond motion of the dye relative to actin.

Cofilin binding reduces the initial anisotropy (r0) in

a non-stoichiometric manner (Figure 5(a)). The

best fits of the data to equation (11) show that a

single bound cofilin affects the initial anisotropy of

90 G24 actin subunits. Thus, the cofilin-mediated

effect can be propagated to vacant subunits in the

cooperativity model,12 the multiple equilibrium

conformations complicate the nearest-neighbor

analysis.

Effect of cofilin on time-resolved phosphorescence anisotropy (TPA) of actin filaments

Cofilin binding has a significant effect on the

phosphorescence anisotropy decays of ErIA-actin

filaments (Figure 4). Light-scattering and sedimentation demonstrate that cofilin does not depolymerize actin under our experimental conditions (data

not shown,12). Therefore, cofilin-induced changes in

Figure 4. Effect of cofilin on the time-resolved

phosphorescence anisotropy decays of ErIA-actin filaments. The [ErIA-actin] is 1.8 mM and the [cofilin] are: 0

(blue), 0.15 (red), 0.8 (green), 1.5 (violet) mM. The inset

shows the same data with the time axis plotted on a log

scale.

Figure 5. Cofilin concentration-dependence of the

initial (r0) and final (rN) anisotropies of ErIA actin. The

continuous lines represent the best fits to equation (11)

and indicate that cofilin affects the initial anisotropy of 90

G24 subunits and the final anisotropy of O400 subunits.

Uncertainty bars represent standard deviations from data

sets collected on four separate days. The actin concentration was 1.8 mM. The binding density was estimated

from the data presented in Figure 3, which are

comparable to our previous determinations with pyrene

actin filaments.12

Cofilin Affects Actin Filament Torsional Dynamics

filament (i.e. there are non-nearest-neighbor

cooperative interactions). This range of

cooperativity represents a lower limit, because the

phosphorescence lifetimes and the total intensity

signal (Figure 2) decrease with added cofilin.

Consequently, the effect of cofilin on the observed

anisotropy is less than the effect on the theoretical

anisotropy (equation (7)), so the cooperative unit is

larger than estimated from the concentrationdependence of the observed anisotropy reduction

(i.e. if quenching did not occur, the slope would be

steeper). The low signal-to-noise ratio at high

[cofilin], due to quenching of phosphorescence

intensity (Figure 2), decreases the reliability of the

anisotropy data as cofilin concentration

approaches saturation. The maximum observed

decrease in the initial anisotropy (r0), from 0.105

G0.007 in actin to 0.069 G0.016 in cofilactin

filaments (Figure 5(a)), indicates an increase in the

half-cone angle of the submicrosecond wobble (qc)

from 37(G2) 8 in actin to 47(G4) 8 in actin filaments

saturated with cofilin (Equation (6)).

The final anisotropy (rN) reaches a minimum at a

cofilin binding density /0.1 (Figure 5(b)), indicating that the cofilin-induced increase in the angular

amplitude of the microsecond rotational motions is

also cooperative. The best fit of the data has a large

uncertainty but indicates that the final anisotropy of

several hundred actin subunits (427G355) are

affected by bound cofilin. This maximal effect of

rN at substoichiometric cofilin binding densities is

consistent with long-range, non-nearest-neighbor

cooperative interactions modulating the internal

dynamics of actin filaments. Filament severing,

predicted to occur at low binding densities and

cluster sizes,12 would also lower rN.

Model-dependent analysis: torsional twist

The effect of cofilin on actin dynamics was

analyzed in terms of the torsional twist model

(equation (8)). In this model, the actin filament is

regarded as an array of cylindrical elementary rods

and the observed anisotropy decay results from the

combined global motions, which represent overall

rigid-body tumbling and intrafilament twisting

motions. Therefore, to determine the intrafilament

torsional constant (a) from the TPA data (equation

(7)) accurately, corrections for rigid-body motions

must be made. Thermal bending motions, which

occur on the millisecond timescale, are too slow to

be detected by TPA. Similarly, rigid-body tumbling

motions can contribute to the microsecond TPA

decay only for those filaments that are much shorter

than the typical 4 mm long filaments observed in the

absence of cofilin (Figure 6).15

Since cofilin-induced fragmentation of actin

could produce filaments that tumble on the timescale of TPA measurements, the equilibrium length

distribution (li) of actin filaments at saturating

cofilin was measured by electron microscopy

(Figure 6) and included in the fit function (equation

(8)), allowing us to separate the effect of rigid-body

993

Figure 6. Length distribution of ErI-actin filaments. The

[ErIA-actin] is 1.8 mM and the [cofilin] are: 0 (a) and 4.0 (b)

mM.

rotations of short actin-cofilin filaments on TPA

from the intrafilament motions. The filament radius

is constrained when fitting the data to determine

the torsional constant (a), so our determination of a

was limited to bare and fully decorated filaments,

which have well-defined homogenous radii. The

radius of an actin filament (a) was taken to be 4.5!

10K9 m based on the maximum diameter of 90–95 Å

reported by Holmes.23 The diameter of a cofilindecorated actin filament was determined to be 6.7!

10K9 m by measuring the width of the bare and

cofilin-decorated actin filament.5 The fit value for

the torsional constant (a) increases by a factor of

about 2 when the assumed radius of bare actin is

reduced from 4.5 nm to 3.5 nm.24 With cofilinsaturated actin, when the assumed radius is

reduced from 6.7 nm to 5.7 nm, the torsional

constant increases by w50%. Therefore, although

the best fit values of the torsional constant (a)

depend on assumptions of actin filament radii, the

uncertainty in determining a is no more than a

factor of 2.

Cofilin binding has minimal effects on the

orientations of absorption and emission dipoles of

ErIA (Table 1), but lowers the spring constant (a)

and thus the torsional rigidity C (calculated as ah)

by a factor of about 20 (Table 1). This indicates that

while cofilin-induced changes in the average actin

filament subunit orientation, as detected from the

ErIA probe at the actin C terminus, are subtle (!108

tilt with respect to the long filament axis), filaments

with bound cofilin are torsionally more flexible,

displaying larger and more rapid microsecond

twisting motions than native actin filaments.

Actin filaments are best described as a continuous

elastic rod.19 However, if the continuous elasticity is

expressed as an elasticity per subunit rise in the

994

Cofilin Affects Actin Filament Torsional Dynamics

Table 1. Effects of cofilin on the structure and dynamics of ErIA-actin filaments

Filament

d

Actin

Cofilactinf

[cofilin]/

[actin]

0

2.2

qa (deg)a

e

44.2 (G1.7)

44.5 (G0.3)

qe (deg)a

C (N m2 radianK1)a

a (N m radianK1)b

hDxic

41.9 (G3.5)

38.1 (G0.5)

2.30 (G1.00)!10

0.13 (G0.06)!10K27

8.36 (G3.6)!10

0.48 (G0.22)!10K19

4.08

16.88

K27

K19

Conditions: 1.8 mM ErIA-actin filaments in 50 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, 0.2 mM ATP, 1 mM NaN3, 20 mM imidazole (pH 6.6),

25 8C.

a

Determined by fitting of the data to equation (7) (subunit height Z5.5 nm).

b

Calculated using equation (9) and a subunit height (h) of 2.75 nm; 1 Nm radianK1Z107 dyn cm radianK1.

c

Calculated using equation (10).

d

Calculated using a filament radius of 4.5 nm.

e

Uncertainties representGone standard deviation from three separate data sets.

f

Calculated using a filament radius of 6.7 nm.

filament (hZ2.75!10K9 m), the root mean squared

average thermal fluctuation of the torsion angle

(hDxi) between adjacent subunits in a filament (i.e.

angular disorder) can be calculated from the

torsional constant (equation (10)25). Cofilin binding

increases the amplitude of the actin subunit torsion

angle fluctuations from 4.08 to 16.88 at 25 8C

(Table 1). This cofilin-induced fourfold increase in

hDxi is independent of the subunit height h, since a is

inversely proportional to h (equation (10)).19 The 48

torsional fluctuation of bare actin filaments

measured here is comparable to the 5–68 angular

disorder observed by electron microscopy image

analysis,26 and more recently using total internal

reflection fluorescence polarization microscopy.27

Effect of subsaturating phalloidin on cofilin binding

and filament dynamics

The ability of phalloidin to cooperatively stabilize

intermonomer bonds in actin28 makes it a useful

tool to examine the role of intersubunit interactions

in the actin–cofilin interaction. Saturating phalloidin has minimal effects on the intensity (Figure 7)

and anisotropy (Figure 7(a) inset) decay of ErIAactin filaments, consistent with previous reports.21,29

Saturating amounts of phalloidin protect actin from

the cofilin-dependent decrease in phosphorescence

intensity and anisotropy (data not shown) because

cofilin does not bind phalloidin-stabilized actin. At

subsaturating phalloidin concentrations (0.1 phalloidin per actin), cofilin can bind actin and

quenches the phosphorescence intensity but minimally affects the changes in anisotropy (Figure 7(b)

inset). This behavior suggests that cofilin binds to

phalloidin-free regions on the filament, locally

quenching the phosphorescence of ErIA, but

phalloidin-induced long-range stabilizing effects

on intermonomer contacts dampen cofilin-induced

changes in torsional flexibility.

The kinetics of cofilin binding to actin filaments

was assayed from the quenching of pyrene actin

fluorescence.12,30 Time-courses of 11.8 mM cofilin

binding to actin filaments displayed a brief lag

phase (Figure 7(c) inset). For simplicity, we treated

the relaxation as a single process even though this is

not an accurate reaction mechanism30 (E.D.L.C. and

W. Cao, unpublished results). The observed time-

course of cofilin (11.8 mM) binding to actin could be

approximated by an exponential with an observed

rate constant of w1.6 sK1. Time-courses of cofilin

binding to phalloidin-stabilized actin filaments

follow double exponentials (Figure 7(c) inset).

Bound phalloidin slowed the observed rate constant of the fast phase and subsaturating phalloidin

concentrations generated maximal inhibition

(Figure 7(c)). The best fit of the data (Figure 7(c))

indicates that a single bound phalloidin inhibits

cofilin binding to 8.6 G0.5 actin subunits in a

filament. This inhibition can be explained by the

stabilizing effect of phalloidin, which extends 10–20

filament subunits.28 The observed rate constants of

the slow phases are 0.002–0.01 sK1, which may be

limited by phalloidin dissociation. Contributions

from photobleaching make it difficult to analyze the

slow rates reliably.

Discussion

Relationship between phosphorescence

intensity, anisotropy and the conformation of

ErIA-actin filaments

The analysis of the effect of cofilin on phosphorescence intensity and anisotropy of ErIA-actin

indicates that cofilin has both local and long-range

effects on actin’s structure and dynamics. Cofilininduced local structural changes in the environment

of the C terminus are indicated by quenching of the

phosphorescence intensity of actin-bound ErIA

(Figures 2 and 3). These changes are probably

facilitated by the proximity (11–30 Å) of cofilin

binding sites to the label on Cys374.5 The subtle

effect of cofilin on the absorption and emission

dipoles of ErIA-actin filaments (Table 1) suggests

that its binding occurs with minimal (!108) tilting

of the ErIA probe with respect to the filament axis,

but the observed decrease in phosphorescence

intensity suggests structural changes in the environment of Cys374 that increase the exposure of the

actin-bound ErIA to quenching by the solvent.

Increased exposure of the dye to the solvent is also

supported by the increased amplitude of the

nanosecond wobbling motions, which are too fast

for the motions of whole monomers, but are

Cofilin Affects Actin Filament Torsional Dynamics

Figure 7. Effect of substoichiometric phalloidin concentrations on cofilin-dependent changes in phosphorescence intensities and anisotropies. (a) Phosphorescence

intensity decay of actin filaments (blue) and actin

filaments saturated with phalloidin (red). Inset: Anisotropy decay of actin filaments (blue) and actin filaments

saturated with phalloidin (red). Only the first 300 ms are

shown for clarity. (b) Phosphorescence intensity decay of

actin filaments (blue), actin filaments with a molar

equivalent of cofilin (green), and actin filaments equilibrated with a molar equivalent of cofilin and 0.1 molar

equivalent of phalloidin (red). Inset: Anisotropy decay of

actin filaments (blue), actin filaments with a molar

equivalent of cofilin (green), and actin filaments equilibrated with a molar equivalent of cofilin and 0.1 molar

equivalent of phalloidin (red). Only the first 300 s are

shown for clarity. (c) Phalloidin concentration-dependence of the observed rate constant for 11.8 mM cofilin

binding to actin filaments as assayed from the quenching

of pyrene fluorescence. The apparent stoichiometry (n)

obtained from the best fit is 0.116 G0.007 phalloidin

bound per actin. The continuous line is the best fit to

equation (12). Uncertainty bars are within the symbols.

The inset shows time-courses of fluorescence quenching

after mixing 23 mM cofilin with pyrene actin filaments

containing (a) 0, (b) 0.1, (c) 0.4, or (d) 0.8 molar equivalent

of bound phalloidin. The final [ErIA-actin] is 1.8 mM in (a)

and (b) and 0.85 mM in (c).

995

compatible with increased mobility of the C

terminus. These local cofilin-induced structural

changes could contribute to the reported changes

at the interface between subdomain 1 and 29 of

adjacent filament subunits, and because of conformational coupling between subdomain 1 and 231

within an individual subunit, to changes in

subdomain 2 conformation.7

It has been proposed that cofilin binding shifts

the equilibrium distribution of thermal conformers.6,7 The reciprocal, [cofilin]-dependent partitioning of the short and long phosphorescence

lifetime conformational states (Figure 3) is consistent with this hypothesis. However, the cofilininduced increase in torsional amplitude between

adjacent filament subunits (hDxi; Table 1) suggests

that cofilin binding also allows actin filaments to

sample novel conformational states by changing the

filament torsional stiffness. In contrast, cofilin

markedly reduces the variability in subunit

torsion angles observed by electron microscopy.6

This observation suggests that electron

microscopy is sampling the long-range cumulative

component of the angular variability, while the

spectroscopic measurements report the local

rotations of an actin subunit or domain about the

helical axis.

The cofilin-induced cooperative change in phosphorescence anisotropy and the large decrease in

torsional rigidity are likely to reflect the change in

filament twist. Differential scanning calorimetry32

favors a mechanism where cofilin binding

destabilizes (i.e. lowers the thermal transition) the

filament lattice cooperatively, as would be expected

from the increased torsional flexibility at substoichiometric cofilin concentrations. Our spectroscopic observations are also consistent with the

results of electron microscopy, which showed that

cofilin cooperatively changes the twist of the actin

filament.6

The binding of cofilin induces long-range

cooperative changes in the microsecond timescale

actin filament dynamics (Figure 5). The nonnearest-neighbor effects on torsional dynamics

may contribute to the acceleration of Pi33 release

and weak Pi binding of cofilin-actin filaments, and

may influence interaction with other regulatory

proteins, particularly those that are sensitive to the

nucleotide state of actin filaments such as the Arp2/

3 complex.34

Long-range cooperative changes in actin filaments are expected to decrease (i.e. dampen) as the

distance from bound cofilin increases. The number

of subunits that could be affected would be dictated

by the energy change of the two twisted conformations and the energy associated with cofilin

binding. The product of the number of affected

subunits and the free energy change of the

transition could not exceed the free energy associated with cofilin binding. Therefore, the observation

that dozens of subunits are affected by an

individual cofilin molecule favors a mechanism

996

where the twist conformations are comparable in

energy, perhaps thermal conformers.

Comparison of methods used to measure the

torsional rigidity of actin filaments

Several methods have been used to estimate the

angular disorder in the torsion angle between

adjacent filament subunits (hDxi) and the torsional

rigidity (C) of actin filaments, including

electron microscopy,24,35,36 electron paramagnetic

resonance,37,38 transient absorption and phosphorescence anisotropy,15,16,18–21 visualization of

rotational motions of beads attached to actin

filaments,39,40 and total internal reflection

fluorescence polarization microscopy. 27 The

values for the torsional rigidity of actin

filaments obtained with these methods range from

w2!10K27 Nm2 15,16,18–21,24,27,35–38 to w5!10K26

Nm2.39,40 This study estimates the torsional rigidity

of actin filaments in solution as 2.3!10K27 Nm2

(Table 1), comparable to previous spectroscopy,15,16,18–21,37,38 electron microscopy24,35,36

and single-molecule measurements.27 Higher

values were obtained with micromanipulation

methods, using large beads in an optical trap,39,40

which more than likely lead to an overestimate of

torsional rigidity.27

Implications for actin filament severing

The observed local changes at the actin C

terminus may account for the effect of cofilin on

actin filament stability. Normal mode analysis of the

actin filament led to the conclusion that the

torsional flexibility of the whole filament could be

significantly affected by reorientation of only a few

residues, such as in the region of the hydrophobic

plug and subdomain 2;23,41–43 such torsionally

strained filaments fragment more easily than

unloaded filaments.39 Cofilin binding to the C

terminus of actin would interfere with formation

of stabilizing longitudinal contacts established by

subdomains 1 and 2 of adjacent subunits.5–7,9,23,28,44,45

Because subdomain 2 also forms lateral interstrand

contacts through contact with residues 262–274,23,46,47

reorganization of subdomain 2 upon cofilin binding7,8 would disrupt the formation of stabilizing

lateral 10,11 filament interactions as well. By

destabilizing subdomain 2 interactions in the

filament, cofilin makes the overall intersubunit

contacts less stiff. Thus, cofilin serves as a molecular

lubricant that allows actin filaments to adopt

otherwise inaccessible conformations. The combination of compromised lateral and longitudinal

filament contacts would, therefore, destabilize the

filament locally and promote severing.

The increase in the torsional flexibility of cofilinactin filaments (i.e. lower torsional constant, a,

Table 1) and larger intersubunit angular disorder

(hDxi, Table 1) is consistent with proposed cofilininduced disruption of longitudinal and lateral

interactions in actin. It is, therefore, likely that the

Cofilin Affects Actin Filament Torsional Dynamics

increased angular disorder (hDxi) induced by cofilin

binding causes local perturbations in filament

conformation and dynamics that promote severing.

Such a mechanism would account for efficient

filament severing at low cofilin binding densities

and cluster sizes.12

The observed effects of phalloidin provide further

insight into the mechanism of cofilin-induced local

and global changes in actin filament. Phalloidin

binding changes the conformation of subdomain 2

cooperatively,28 dampens the cofilin-dependent

torsional dynamics of actin filaments (Figure 7(b)),

has long-range effects stabilizing intermonomer

bonds, and cooperatively decreases the rate of

cofilin binding (Figure 7(c)), supporting our

hypothesis that the cofilin binding affinity is

dictated by the conformation of subdomain 2 as

well as actin filament torsional dynamics.12 Significant quenching of phosphorescence without binding-related changes in dynamics, as observed at

substoichiometric concentrations of phalloidin

(Figure 7(b)) further suggests that the mechanism

of long-range effects of cofilin on actin’s dynamics

involves destabilization of intermonomer bonds.

Comparison with other actin-binding proteins

The observed effect of cofilin on the microsecond

dynamics of actin represents another example of

cooperative changes in actin filaments induced by

interaction with regulatory proteins. Both gelsolin15

and myosin subfragment 116 cooperatively affect

the conformation and dynamics of actin filaments.

Although each of these proteins affects the environment of the actin C terminus, the changes in TPA

and dynamics are distinct (i.e. myosin increases but

cofilin and gelsolin lower the torsional rigidity),

indicating that the changes are specific to the

structure of the binding interfaces.

Materials and Methods

Proteins

Rabbit skeletal muscle actin was purified as

described.19,48 Recombinant human cofilin was expressed

and purified as described.12,49 All proteins were dialyzed

exhaustively against KMI6.6 buffer (50 mM KCl, 2 mM

MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, 0.2 mM ATP, 1 mM NaN3, 20 mM

imidazole (pH 6.6)) prior to use.

Labeling of actin with optical probes

Actin (48 mM) was polymerized with 50 mM KCl,

20 mM Tris (pH 7.5), and ErIA, freshly dissolved in

dimethylformamide, was added at a concentration of

480 mM. After 2 h incubation at 25 8C, the labeling reaction

was quenched with 5 mM DTT, actin filaments were

centrifuged for 1 h at 200,000g, pellets were suspended in

G buffer and clarified by centrifugation at 350,000g.

Samples were polymerized with 0.1 M KCl and centrifuged for 1 h at 200,000g. Pellets were suspended and

dialyzed against KMI6.6 buffer without magnesium.

997

Cofilin Affects Actin Filament Torsional Dynamics

Pyrene actin was prepared essentially as described.12 The

labeling efficiencies were R90%.

Phosphorescence

Phosphorescence measurements were made at 25 8C in

KMI6.6 buffer supplemented with an oxygen-scavenging

enzyme mixture (36 mg mlK1 catalase, 45 mg mlK1 glucose, 55 mg mlK1 glucose oxidase). Actin filaments and

cofilin-actin filaments were prepared by mixing preformed eryhrosine-labeled (ErIA) actin filaments with a

range of cofilin concentrations and equilibrated at room

temperature for at least 20 min. ErIA was excited at

540 nm with a vertically polarized 10 ns pulse from XeClpumped dye laser (Compex 120, Lambda Physics) using

5 mM coumarin 548 in ethanol, operating at a repetition

rate of 100 Hz. Phosphorescence emission was selected by

a colored glass cut-off 670 nm filter (Corion), detected by a

photomultiplier (R928, Hamamatsu), and digitized by a

transient digitizer (CompuScope 14100, GaGe) using time

resolution of 1 ms/channel, with an analog filter time

constant of 3 ms.

The time-resolved phosphorescence intensity I(t) and

anisotropy decays r(t) were calculated according to:

IðtÞ Z Ivv ðtÞ C 2GIvh ðtÞ

(1)

Ivv ðtÞKGIvh ðtÞ

Ivv ðtÞ C 2GIvh ðtÞ

(2)

and

rðtÞ Z

where Ivv(t) and Ivh(t) are vertically and horizontally

polarized components of the emission signal that were

detected at 908 with a single detector equipped with a

Polaroid sheet polarizer alternating between vertical and

horizontal orientations every 500 laser pulses. G is an

instrumentation correction factor, determined by

measuring the anisotropy of ErIA-labeled bovine serum

albumin in 98% glycerol and adjusting G to give a

residual anisotropy value of zero, the theoretical value

for an isotropically tumbling chromophore. The timedependent anisotropy decays were obtained by recording

60 cycles of 1000 pulses (500 in each orientation of the

polarizer) at a laser repetition rate of 100 Hz.

The phosphorescence intensity decays (I(t)) were

analyzed by fitting to a double-exponential:

Kt=t1

IðtÞ Z I1 exp

Kt=t2

C I2 exp

C I3

Ii ti

I1 t1 C I2 t2 C I3 t3

(4)

The lifetime of the rapidly decaying component (t3)

was assumed to be 1 ms, which is the upper limit, since it

is not observed within the 3 ms dead-time for data

acquisition (Figure 2). If the value of t3 is !1 ms,

population of X3 (Figure 3) would be lower.

The anisotropy decays (r(t)) were fitted to doubleexponentials (nZ2) plus a constant (rN):

rðtÞ Z r1 expKt=f1 C r2 expKt=f2 C rN

where, r0Z0.205 for ErIA immobilized in PMMA resin.19

The anisotropy decays (r(t)) were further analyzed in

terms of the theory of Schurr51,52 describing the rotational

diffusion of a flexible filament with mean local cylindrical

symmetry, and applied to TPA of ErIA-actin.19 According

to this model, the filament is regarded as a randomly

labeled array of cylindrical subunits. The anisotropy (r(t))

describes the mean-squared displacements of the subunit

elementary rods (and the rigidly bound probe) due to

combined intrafilament twisting and rigid-body motions

of the whole filament. If the filaments have a broad length

distribution, where each filament of length li is composed

of Ni elementary rods with height h equal to the height of

an individual actin subunit, the anisotropy r(t) reflects the

sum of contributions from the filaments within each

particular group:

rðtÞ Z k

(5)

where ri is the amplitude of the of the ith anisotropy

iZp

nZ2 X

X

A n Cni ðtÞ

(7)

nZ0 iZ1

where k is an “amplitude reduction factor” that accounts

for motions on the timescale more rapid than the time

resolution of detection,19 p is the total number of groups

in the length distribution histograms (Figure 6) and Ān

defines the amplitudes of the motions.

The torsional correlation function (Cni (t)) for filaments

in the length group li is defined as:19

h 2

i

n tkB T

exp K

ðNiC1Þg

Cni ðtÞ Z

Ni C 1

"

#

N

N

i C1

i C1

X

X

2

2 2

Kt=tsi

exp Kn

dsi Qmsi ð1Ke

Þ

!

mZ1

(3)

where Ii is the amplitude and ti is the triplet excited-state

lifetime of the ith relaxation, and t is time. Fits were

performed with unconstrained amplitude and lifetime

parameters, and then with the lifetimes constrained to the

values of F-actin.

Mole fractions (X) of the observed intensity decays

were calculated from:

Xi Z

decay, fi is the rotational correlation time of the ith

relaxation, and rN is the final anisotropy. The initial

anisotropy (r0) is defined as r(tZ0).

The cofilin-induced changes in the initial anisotropy

were analyzed in terms of the wobble-in-a-cone model.

The isotropic wobble of the observed transition dipole of

the probe in a cone was described by the cone half angle

qc:50

r0

cos qc ð1 C cos qc Þ 2

Z

(6)

0:205

2

d2si Z

kB Ttsi

g

sZ2

tsi Z

4a sin

2

g

ðsK1Þp

2ðNiC1Þ

and

sffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

mK 12 ðsK1Þp

2

cos

ð1Kdsi Þ

Qmsi Z

ðNi C 1Þ

ðNi C 1Þ

sffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

1

C dsi

ðNi C 1Þ

(8)

where kB is Boltzmann’s constant (1.381!10K23 Nm KK1),

T is the absolute temperature (298 K), Ni is the number of

subunits in filaments with length li, t is the relaxation

time, d2 is the mean-square amplitude of the sth normal

mode, dsi is the Kronecker delta function, g is the

frictional coefficient for rotation of an elementary rod of

height h about the filament long axis, defined by gZ

4pha2h, h is the solvent viscosity (1 cP), a is the filament

radius (4.5!10K9 m for pure actin and 6.7!10K9 m for

cofilin-decorated actin), a is the intrafilament torsional

998

Cofilin Affects Actin Filament Torsional Dynamics

constant and mZ1, 2,., N iC1. Note that kB T/g

represents the long-axis rotational diffusion coefficient

of an elementary rod, commonly referred to as Dk.

Fitting r(t) to equation (7) with the values of h, a, h, and

T constrained yields three parameters: qa and qe, the

angles between the absorption and emission dipoles of

the bound dye and the filament axis, respectively, and the

torsional constant a, which characterizes the elastic

properties of actin and reflects the torque force required

to twist a 1 m radius filament by 1 radian (57.38). A larger

torsional constant indicates a greater resistance to

twisting (i.e. more stiff) under applied external rotational

forces.

The torsional rigidity C is defined by the torsional

constant (a) and the long-axis height (h) of an elementary

rod (i.e. filament subunit) as:

C Z ah

(9)

The root-mean-square average fluctuation of the

torsion angle (hDxi in radians, 1 rad Z57.38) between

adjacent filament subunits was calculated from25:

rffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

kB T

(10)

hDxi Z

a

Equilibrium binding equations

The cofilin concentration-dependence of the initial (r0)

and final (rN) anisotropies were fitted to:

robs Z rCA KðrCA KrA Þð1KvÞn

(11)

where robs is the observed anisotropy (initial or final), rA is

the anisotropy (initial or final) of actin alone and rCA is

that of a cofilin-decorated actin filament, v is the cofilin

binding density (bound cofilin per actin), and n is the

stoichiometry (molar ratio) of cofilin that maximally

affects the robs of actin (i.e. number of actin subunits

affected by bound cofilin).

Pyrene fluorescence

Phalloidin inhibition of cofilin binding was assayed

from the time-courses of pyrene fluorescence quenching12,30 after mixing 11.8 mM cofilin with 0.85 mM pyreneactin filaments (final concentrations after mixing).

Measurements were made at 25.0(G0.1) 8C in KMI6.6

buffer with an Applied Photophysics SX.18MV-R

stopped-flow apparatus. A 400 nm colored glass emission

filter was used to monitor fluorescence (lexZ366 nm).

Time-courses of pyrene fluorescence changes were

fitted to single or double-exponentials. The phalloidinconcentration-dependence of the fast observed rate

constant (kobs) of fluorescence quenching was fitted to:

kobs Z ko C ðkN Kko Þ

0

B

!B

@

½Ph

½A

Kd

C ½A

r

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

ffi1

Cn K

½Ph

½A

2n

Kd

C ½A

Cn

2

K4 ½Ph

½A n C

C

A

(12)

where ko is the observed rate constant of cofilin binding to

actin filaments in the absence of phalloidin, kN fluorescence intensity is the observed rate constant of cofilin

binding to actin filaments in the presence of saturating

phalloidin, [Ph] and [A] are the total phalloidin and actin

concentrations respectively, Kd is the apparent dissociation equilibrium constant of phalloidin binding to

rabbit muscle actin filaments under our experimental

conditions (20 nM 53), and n is the stoichiometry (molar

ratio) of bound phalloidin that maximally inhibits cofilin

binding. The stoichiometry (n), initial (ko) and final (kN)

observed rate constants were allowed to float when

fitting.

Electron microscopy

Actin filaments and cofilactin filaments were prepared

by mixing preformed erythrosin-labeled actin filaments

with a range of cofilin concentrations, equilibrated at

room temperature for at least 20 min, adsorbed to glowdischarged carbon-coated copper grids, negatively

stained with 1% (w/v) uranyl acetate and visualized

with a JOEL 100 CX electron microscope at an accelerating

voltage of 80 kV.

Cosedimentation

Samples (200 ml) of ErIA-F-actin (1.8 mM) and cofilin

(0.1, 2 or 8 mM) were prepared with oxygen-removing

enzymes as for TPA experiments. Samples were equilibrated at 25 8C for 10 min then centrifuged for 30 min at

400,000g in a TLA-100 rotor, which is sufficient to pellet

even very short filaments (lavg w0.13 mm; w47 subunits).54

The fraction of ErIA-actin remaining in the supernatant

was determined by measuring absorbance of the probe at

538 nm of samples before centrifugation and supernatants.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Wenxiang Cao for engaging

discussions, Adrian O. Olivares and James P.

Robblee for assistance with some of the cofilin

preparations used in this study, and Brian Tucker

for assistance with the kinetics of cofilin binding to

pyrene actin filaments. This work was supported by

a Hellman Family Fellowship (to E.M.D.L.C.),

grants from the American Heart Association

(0235203N to E.M.D.L.C.), the National Science

Foundation (MCB-0216834 to E.M.D.L.C.), and the

NIH (AR32961 to D.D.T.).

References

1. Du, J. & Frieden, C. (1998). Kinetic studies on the

effect of yeast cofilin on yeast actin polymerization.

Biochemistry, 37, 13276–13284.

2. Moriyama, K. & Yahara, I. (1999). Two activities of

cofilin, severing and accelerating directional

depolymerization of actin filaments, are affected

differentially by mutations around the actin binding

helix. EMBO J., 6752–6761.

3. Pope, B. J., Gonsior, S. M., Yeoh, S., McGough, A. &

Weeds, A. G. (2000). Uncoupling actin filament

fragmentation by cofilin from increased subunit

turnover. J. Mol. Biol. 298, 649–661.

4. Carlier, M. F., Laurent, V., Santolini, J., Melki, R.,

999

Cofilin Affects Actin Filament Torsional Dynamics

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

Didry, D., Xia, G. X. et al. (1997). Actin depolymerizing

factor (ADF/cofilin) enhances the rate of filament

turnover: implication in actin based motility. J. Cell.

Biol. 136, 1307–1322.

McGough, A., Pope, B., Chiu, W. & Weeds, A. G.

(1997). Cofilin changes the twist of F-actin: implication for actin filament dynamics and cellular

function. J. Cell. Biol. 138, 771–781.

Galkin, V. E., Orlova, A., Lukoyanova, N., Wriggers,

W. & Egelman, E. H. (2001). Actin depolymerizing

factor stabilizes an existing state of F-actin and change

the tilt of F-actin subunits. J. Cell. Biol. 153, 75–86.

Galkin, V. E., Orlova, A., VanLoock, M., Shvetsov, A.,

Reisler, E. & Egelman, E. H. (2003). ADF/cofilin use

an intrinsic mode of F-actin instability to disrupt actin

filaments. J. Cell. Biol. 163, 1057–1066.

Muhlrad, A., Kudryashov, D., Michael Peyser, Y.,

Bobkov, A. & Almo, S. C. (2004). Cofilin induced

conformational changes in F-actin expose subdomain

2 to proteolysis. J. Mol. Biol. 342, 1559–1567.

Bobkov, A. A., Muhlrad, A., Kokabi, K., Vorobiev, S.,

Almo, S. C. & Reisler, E. (2002). Structural effects of

cofilin on the longitudinal contacts in F-actin. J. Mol.

Biol. 323, 739–750.

Bobkov, A. A., Muhlrad, A., Shvetsov, A., Benchaar, S.,

Scoville, D., Almo, S. C. & Reisler, E. (2004). Cofilin

(ADF) affects lateral contacts in F-actin. J. Mol. Biol.

337, 93–104.

McGough, A. & Chiu, W. (1999). ADF/cofilin

weakens lateral contacts in the actin filament. J. Mol.

Biol. 291, 513–519.

De La Cruz, E. M. (2005). Cofilin binding to muscle

and non-muscle actin filaments: isoform-dependent

cooperative interactions. J. Mol. Biol. 346, 557–564.

Isambert, H., Venier, P., Maggs, A. C., Fattoum, A.,

Kassab, R., Pantaloni, D. & Carlier, M. F. (1995).

Flexibility of actin filaments derived from thermal

fluctuations. Effect of bound nucleotide, phalloidin,

and muscle regulatory proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 270,

11437–11444.

Rebello, C. A. & Ludescher, R. D. (1999). Differential

dynamic behavior of actin filaments containing

tightly-bound Ca2C or Mg2C in the presence of

myosin heads actively hydrolyzing ATP. Biochemistry,

38, 13288–13295.

Prochniewicz, E., Zhang, Q., Janmey, P. A. & Thomas,

D. D. (1996). Cooperativity in F-actin: binding of

gelsolin at the barbed end affects structure and

dynamics of the whole filament. J. Mol. Biol. 260,

756–766.

Prochniewicz, E. & Thomas, D. D. (1997). Perturbations of functional interactions with myosin induce

long-range allosteric and cooperative structural

changes in actin. Biochemistry, 36, 12845–12853.

Allen, P. G., Shuster, C. B., Kas, J., Chaponnier, C.,

Janmey, P. A. & Herman, I. M. (1996). Phalloidin

binding and rheological differences among actin

isoforms. Biochemistry, 35, 14062–14069.

Prochniewicz, E. & Thomas, D. D. (1999). Differences

in structural dynamics of muscle and yeast actin

accompany differences in functional interactions with

myosin. Biochemistry, 38, 14860–14867.

Prochniewicz, E., Zhang, Q., Howard, E. C. &

Thomas, D. D. (1996). Microsecond rotational

dynamics of actin: spectroscopic detection and

theoretical simulation. J. Mol. Biol. 255, 446–455.

Prochniewicz, E., Walseth, T. F. & Thomas, D. D.

(2004). Structural dynamics of actin during active

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

interaction with myosin: different effects of weakly

and strongly bound myosin heads. Biochemistry, 43,

10642–10652.

Yoshimura, H., Nishio, T., Mihashi, K., Kinosita, K., Jr

& Ikegami, A. (1984). Torsional motion of eosinlabeled F-actin as detected in the time-resolved

anisotropy decay of the probe in the sub-millisecond

time range. J. Mol. Biol. 179, 453–467.

Mihashi, K., Yoshimura, H., Nishio, T., Ikegami, A. &

Kinosita, K., Jr (1983). Internal motion of F-actin in

10K6–10K3 s time range studied by transient absorption anisotropy: detection of torsional motion.

J. Biochem. 93, 1705–1707.

Holmes, K. C., Popp, D., Gebhard, W. & Kabsch, W.

(1990). Atomic model of the actin filament. Nature,

347, 44–49.

Egelman, E. H. & Padrón, R. X-r. (1984). ray diffraction

evidence that actin is a 100 Å filament. Nature, 307,

56–58.

Barkley, M. D. & Zimm, B. H. (1979). Theory of

twisting and bending of chain macromolecules;

analysis of the fluorescence depolarization of DNA.

J. Chem. Phys. 70, 2991–3007.

Egelman, E. H., Francis, N. & DeRosier, D. J. (1983).

Helical disorder and the filament structure of F-actin

are elucidated by the angle-layered aggregate. J. Mol.

Biol. 166, 605–629.

Forkey, J. N., Quinlan, M. E. & Goldman, Y. E. (2005).

Measurement of single macromolecule orientation by

total internal reflection fluorescence polarization

microscopy. Biophys. J. 89, 1261–1271.

Orlova, A., Prochniewicz, E. & Egelman, E. H. (1995).

Structural dynamics of F-actin: II. Cooperativity in

structural transitions. J. Mol. Biol. 245, 598–607.

Rebello, C. A. & Ludescher, R. D. (1998). Influence of

tightly bound Mg2C and Ca2C, nucleotides, and

phalloidin on the microsecond torsional flexibility of

F-actin. Biochemistry, 37, 14529–14538.

Ressad, F., Didry, D., Xia, G. X., Hong, Y., Chua, N. H.,

Pantaloni, D. & Carlier, M.-F. (1998). Kinetic analysis

of the interaction of actin-depolymerizing factor

(ADF)/cofilin with G- and F-actins. J. Biol. Chem.

273, 20894–20902.

Crosbie, R. H., Miller, C., Cheung, P., Goodnight, T.,

Muhlrad, A. & Reisler, E. (1994). Structural connectivity in actin: effect of C-terminal modifications on

the properties of actin. Biophys. J. 67, 1957–1964.

Dedova, I. V., Nikolaeva, O. P., Mikhailova, V. V., dos

Remedios, C. G. & Levitsky, D. I. (2004). Two opposite

effects of cofilin on the thermal unfolding of F-actin: a

differential scanning calorimetric study. Biophys.

Chem. 110, 119–128.

Blanchoin, L. & Pollard, T. D. (1999). Mechanism of

interaction of Acanthamoeba actophorin (ADF/cofilin)

with actin filaments. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 15538–15546.

Blanchoin, L., Pollard, T. D. & Mullins, R. D. (2000).

Interactions of ADF/cofilin. Arp2/3 complex, capping protein and profilin in remodeling of branched

actin filament networks. Curr. Biol. 10, 1273–1282.

Egelman, E. H., Francis, N. & DeRosier, D. J. (1982).

F-actin is a helix with a random variable twist. Nature,

298, 131–135.

Egelman, E. H. & DeRosier, D. J. (1992). Image

analysis shows that variations in actin crossover

spacings are random, not compensatory. Biophys. J.

63, 1299–1305.

Thomas, D. D., Seidel, J. C. & Gergely, J. (1979).

Rotational dynamics of spin-labeled F-actin in the

sub-millisecond time range. J. Mol. Biol. 132, 257–273.

1000

Cofilin Affects Actin Filament Torsional Dynamics

38. Ostap, E. M., Yanagida, T. & Thomas, D. D. (1992).

Orientational distribution of spin-labeled actin

oriented by flow. Biophys. J. 63, 966–975.

39. Tsuda, Y., Yasutake, H., Ishijima, A. & Yanagida, T.

(1996). Torsional rigidity of single actin filaments and

actin-actin bond breaking force under torsion

measured directly by in vitro micromanipulation.

Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 12937–12942.

40. Yasuda, R., Miyata, H. & Kinosita, K., Jr (1996). Direct

measurement of the torsional rigidity of single actin

filaments. J. Mol. Biol. 227, 236.

41. Lorenz, M., Popp, D. & Holmes, K. C. (1993).

Refinement of the F-actin model against X-ray fiber

diffraction data by the use of a directed mutation

algorithm. J. Mol. Biol. 234, 826–836.

42. Tirion, M. M., ben-Avraham, D., Lorenz, M. &

Holmes, K. C. (1995). Normal modes as refinement

parameters for the F-actin model. Biophys. J. 68, 5–12.

43. ben-Avraham, D. & Tirion, M. M. (1995). Dynamic

and elastic properties of F-actin: a normal-modes

analysis. Biophys. J. 68, 1231–1245.

44. Orlova, A. & Egelman, E. H. (1993). A conformational

change in actin subunit can change the flexibility of

the actin filament. J. Mol. Biol. 232, 334–341.

45. Kim, E. & Reisler, E. (1996). Intermolecular coupling

between loop 38–52 and the C-terminus in actin

filaments. Biophys. J. 71, 1914–1919.

46. Chen, X., Cook, R. K. & Rubenstein, P. A. (1993). Yeast

actin with a mutation in the “hydrophobic plug”

between subdomains 3 and 4 (L266D) displays a coldsensitive polymerization defect. J. Cell. Biol. 123,

1185–1195.

47. Feng, L., mKim, E., Lee, W. L., Miller, C. J., Kuang, B.,

Reisler, E. & Rubenstein, P. A. (1997). Fluorescence

probing of yeast actin subdomain 3/4 hydrophobic

loop 262–274. Actin-actin and actin-myosin interactions in actin filaments. J. Biol. Chem. 272,

16829–16837.

48. Spudich, J. A. & Watt, S. (1971). Regulation of skeletal

muscle contraction. I. Biochemical studies of the

interaction of the tropomyosin-troponin complex

with actin and the proteolytic fragments of myosin.

J. Biol. Chem. 246, 4866–4876.

49. Yeoh, S., Pope, B., Mannherz, H. G. & Weeds, A. G.

(2002). Determining the differences in actin binding

by human ADF and cofilin. J. Mol. Biol. 315, 911–925.

50. Kinosita, K., Kawato, S. & Ikegami, A. (1977).

A theory of fluorescence polarization decay in

membranes. Biophys. J. 20, 289–305.

51. Allison, S. A. & Schurr, S. A. (1979). Torsion dynamics

and depolarization of fluorescence of linear macromolecules I. Theory and application to DNA. Chem.

Phys. 41, 35–59.

52. Schurr, J. M. (1984). Rotational diffusion of deformable macromolecules with mean local cylindrical

symmetry. Chem. Phys. 84, 71–96.

53. De La Cruz, E. M. & Pollard, T. D. (1996). Kinetics and

thermodynamics of phalloidin binding to actin

filaments from three divergent species. Biochemistry,

35, 14054–14061.

54. Schmitz, S., Grainger, M., Howell, S., Calder, L. J.,

Gaeb, M., Pinder, J. C. et al. (2005). Malaria parasite

actin filaments are very short. J. Mol. Biol. 349,

113–125.

Edited by J. Karn

(Received 24 June 2005; received in revised form 6 September 2005; accepted 9 September 2005)

Available online 26 September 2005