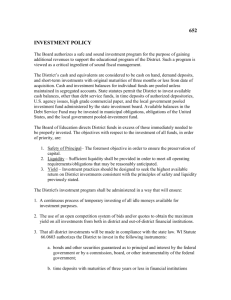

of By Idle Cash

advertisement