Document 10325306

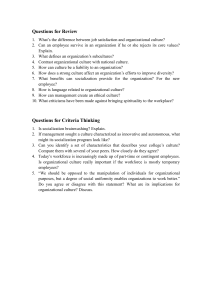

advertisement