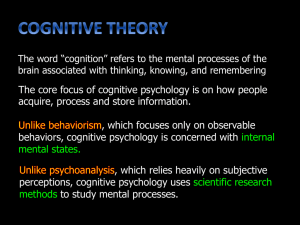

Chapter 3: Cognitive Structures and Processes in Cross-Cultural Management

advertisement