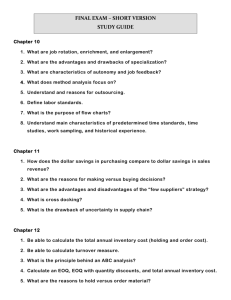

Determining economic inventory policies in a multi-stage just-in-time

advertisement

Internutional

Journal

of Production

Economics,

30-31

(1993)

531

531-542

Elsevier

Determining economic

just-in-time production

A. Gunasekaran’,

S.K. Goyalb,

inventory

system

T. Martikainen”

policies in a multi-stage

and P. Yli-Olli”

aSchool qf Business Studies, Unirersit_v oj’ Vaasa, 65101

b Department

@‘Decision

Scrences

& MIS.

Concordia

Vaasa. Finland

Uhersity,

Montreul,

Que. H3G

Ih48,

Canada

Abstract

New manufacturmg concepts, such asJust-m-time

(JIT) productlon. and quality at source tremendously impact on productwty

and quality in many manufacturmg

systems. In order to implement the JIT manufacturing

concept. one has to analyze Its

consequence

on lot-slzmg and work-in-process

Inventory

Realising the significance of modelling such a sltuatlon, a mathematlcal model IS proposed to establish the relationshlp

between the quality at source. work-in-process

Inventory and lot-sizes m

a multi-stage JIT production

system The model along with a search method is used to determine the economx

production

quantltles (EPQs) by mmlmizmg the total system cost.

1. Introduction

Just-in-time

is a system that produces the

required item at the time and in the quantities

needed. Since the excellent work by Schonberger [l] on Japanese manufacturing

techniques,

a considerable progress has been made on the

methods and techniques related to the application of JIT concepts. Sugimori et al. [27] offered many useful insights into the Toyota JIT

manufacturing

system and its operational

issues. Lot-sizing problems are getting recognized all the time as they are practical and

exist almost in all types of production systems,

including JIT, flexible manufacturing

systems,

etc. Although, the batch size of one is preferable in JIT, but still there are set-up costs

associated with processing the products as well

as other technological

and operational

constraints. Nevertheless, they lead to a problem

of lot-sizing

in JIT production

systems.

Correspondence

to: A. Gunasekaran,

Studies, University

0925-5273/93/$06.00

School of Business

of Vaasa, 65101 Vaasa, Finland.

0

1993 Elsevier

Science Publishers

However, there have been relatively few models

and approaches

reported

for the lot-sizing

problems in JIT manufacturing

systems. Recently, Gunasekaran

et al. [3] reviewed the

available literature on JIT systems with an

objective of identifying the gap between theory

and practice based on suitable classification

criterion. They point out that there is a need

for mathematical

and simulation

models to

solve the problems of design, operational, and

justification in JIT manufacturing

systems. In

addition, they presented future research directions for modelling and analysis of JIT production systems.

Philipoom et al. [4] studied the factors that

influence the number of kanbans required in

the implementation

of JIT techniques and suggested in Ref. [S] a mathematical

programming approach for determining the economic

lot-sizes

in a JIT manufacturing

system.

Spence and Porteus [6] presented a model for

the set-up cost reduction.

The change in

inventory control concept has been suitably

motivated

and focussed

by Zangwill

[7].

Porteus [8-lo] presented a number of useful

B.V. All rights reserved.

ideas for developing various support systems

in JIT production

and quality control with

appropriate

mathematical

models. Funk [ 1 l]

presented attributes

of a JIT manufacturing

system, and compared various inventory cost

reduction

strategies in a JIT manufacturing

system. Bard and Golany

[12] formulated

a mixed integer programming

model to determine the number of kanbans required for each

product by minimizing the set-up cost, inventory holding cost, and shortage cost. However,

their model is applicable only for an assembly

system. Sipper and Shapira [ 131 developed

a decision rule to facilitate a priori classification of a production

system that would utilize

a JIT or WIP type inventory control policy.

Karmarkar

[ 141 investigated

and differentiated the push, pull, and hybrid control systems. Karmarkar

and Kekre [ 151 presented

a model to determine

the optimal batching

policies in a kanban system. Bitran and Chang

1161 offered a number of mixed integer programming formulations

to address the problems of product structure. Axsater and Rosling

[ 171 investigated

under what circumstances

(i.e., system configuration

and control rules)

policies based on echelon stocks are superior

to policies based on installation

stocks. Recently, Gunasekaran

et al. [IS] offered a model

for a multi-stage production

system to determine the optimal number of machines required

for achieving the JIT production.

Moreover, lot-sizing problem in JIT manufacturing systems considering

the quality at

the source has not been given due consideration. The quality at the source involves controlling the process whenever it drifts from

normal process condition.

It requires shutdown and start-up of the machines in order to

bring the process to normal operating conditions. The related inventory costs and service

costs that are arising from these activities must

be considered while determining the economic

lot-sizes. Furthermore,

the purpose of balancing the production

rates between stages is predominant in any JIT production

systems, and

this is an important

problem at the planning

level in order to identify the bottle-neck operations, balancing of production,

and number of

kanbans required to achieve the JIT production. A model is developed

in this paper

to determine

the optimal batch sizes considering the impact of the process control

which would lead to a minimum total system

cost.

The rest of this paper is as follows: The

mathematical

model is presented in Section 2.

An example problem is presented in Section 3.

Section 4 provides the details on the results

obtained and the corresponding

analysis. Section 5 offers discussions

on the model

developed

and its limitations.

Finally, the

conclusions

of this research work are presented in Section 6.

2. Mathematical

model

The proposed mathematical

model here estimates the total system cost in a JIT manufacturing system as a function of the batch sizes at

each stage and for all products.

2.1.

i

j

‘j

Dl

A,j

Qii

t

LJ

Cl,

ciO

product index (i = 1, 2,. . . , M),

stage index (j = 1. 2,. . . , N),

number of machines at stage j,

demand for product i per unit time or per

year,

set up cost per set-up for product i at

stage j,

batch size for product i at stagej (decision

variable),

priority assigned in processing (capacity

allocation) product i at stage j,

penalty cost due to imbalance in production rates between stages j and j + 1,

mean process drift rate while processing

product i at stage j,

mean service rate for bringing the process

to normal operating condition for product i at stage j,

processing time per unit of product i at

stage j.

cost per unit product i after processing at

stage j,

raw material cost per unit product i,

A. Gunasekaran

H

Rij

Tij

Li,

Gij

/I

d:

Z

et al.lDetermming

inventory

cost per unit investment

per

unit time period,

number of production cycles for the given

demand of product i at stage j,

processing time for a batch of product i at

stage j,

average completion

time for a batch of

product i at stage j,

average cost per unit of product i between

stages j and j + 1,

production

rate for product i at stage j,

lower bound on the value of batch size for

product i,

total system cost.

2.2. Assumptions

The following assumptions are made in developing the model:

(i) Demand

for each product

is uniform,

deterministic,

and known.

(ii) Set-up c OSt per set-up is constant, independent of set-up sequence, and batch

sizes.

(iii) For any process, the process drifts follow

Poisson distribution,

and the service time

for each drift follows exponential distribution with average drift and service rates,

respectively.

(iv) Once the process goes out of control, the

machine automatically

stops producing

defective products.

(v) There is no finished product inventory

cost as the products will be dispatched

once the processing is completed at the

final stage.

2.3. The basic model

The total system cost consists of the following costs: (1) set-up cost, (2) cost due to process

control, and (3) cost due to imbalance in production rates. These costs are derived hereunder.

2.3.1.

Set-up cost

The total set-up cost considering

ucts and stages is given by

all prod-

economx

inventory policies

533

(1)

2.3.2. Cost due to process control for quality

at the source

This cost arises from waiting of batches due

to stopping and restarting the machines for

controlling

the process. This process control

supports the “quality at the source” which

undoubtedly improves the quality and reduces

the level of scrappage or defective products. In

most of the occasions, the start-up and shut

down of the machines for controlling the process lead to an in-process inventory carrying

cost due to waiting for the process being

brought to the normal operating condition.

But at the same time, the scrappage level can

be reduced.

The processing time for a batch is given by

TLj= Qlj X

t,j.

(2)

It has been assumed here that the time between two successive drifts of the process at

a particular machine follows exponential distribution. Hence, the number of drifts per unit

time follows Poisson process with mean rate of

drifts. The drift rate is a function of the machine age, motivation

of the workers in performing the process, and the nature of the

process. All these decide the drift rate for a particular product at a stage. Depending upon the

nature of process control required and the skill

of the worker, the service time required to

bring the process to a normal working condition varies. Therefore, it is assumed that the

service time required for each process control

task follows exponential

distribution

with

mean service rate.

Suppose, the operator is an M/M/l server

(or a server when there are Sj machines at stage

j). Every time a machine drifts it has to be

serviced by the operator. From M/M/l queuing theory, the total time spent (waiting time

plus service time per drift) by a batch per drift

can be estimated using the M/M/l

(infinite

source) queuing formula (see Ref. [ 191).

(3)

The average time spent by the batch due to

process drifts while processing that batch can

be obtained as

(4)

The average total time required (processing

time for batch + average time spent by the

batch due to process drifts) for product i at

stagej to complete the processing of a batch is

given by

Lij = T,,

(3

The number of production

cycles per unit

time (per year) for product i at stage j is represented by

2.3.3. Cost due to irnbalmce

rates het,\?een successive stages

irz productiort

The main aim of any production

system

which intends to implement JIT is to balance

the production

rates between successive production stages. The aspects of quality at the

source have been modelled

by Goyal and

Gunasekaran

[20]. However, they considered

solely a traditional production

system in their

article.

The production rate for a particular product

depends upon the number of machines actually used for a product.

If more than one

machine is used for a product, then the production rate will be much higher than that of

with only one machine. However, the required

production

rate to balance the production

between consecutive

stages is an important

subject matter. The production rate for a product at a stage is a function of the total process

completion time of a batch, priority assigned

to the product for processing, and the number

of machines used for processing the product at

the stage, etc.

The production rate for product i from stage

j can be calculated using Eq. (8) as

(9)

where

Since a process drift may occur at any time

during the processing of a batch of a product,

the value of the per unit product at which the

drift occurs may be difficult to obtain. Hence,

the average cost per unit product has been

accounted to compute the cost due to process

control. This cost can be calculated as

(7)

The total inventory

ing is estimated as

cost due to process drift-

(Rt, Qij Tij Gij)

(Q

C &,j = 1,

forj

= 1, 2,. . ., N.

i=l

The parameter

~,j indicates the priority assigned for processing product i at stage j. This

parameter selects the number of machines to

be assigned for a particular product at a stage.

In practice the value of &ij is being estimated

based on the marketing and financial performances. It has been assumed here that the

machines at each stage have identical capacities.

In order to achieve a balance among production rates, we have considered

a penalty

cost (amplified one) which encompasses all the

relevant costs associated with imbalance in the

A. Gunasekaran

et al..lDetermining economic inventory policies

rates, The cost due to imbalance in

rates between stages j and j + 1 is

production

production

given by

(10)

The penalty cost due to imbalance in production rates (Qij) may include the following costs:

(i) inventory cost due to waiting of batches, (ii)

shortage costs, (iii) cost due to idleness of the

facilities, etc. Depending upon the production

configuration,

for example in assembly systems, there may be integer multiple processing

rates at successive stages.

Total cost due to imbalance in production

rates considering

all products and stages is

given by

N-l

i-M

i

1

c j=lC

IAij

-

)Lij+

I

1

(11)

1=1

2.3.4.

Minimize

+

5i

i=l

{Rij Qij Tij G,j}

ix1

M

N-’

C C

+

i=l

(15)

Constraint (13) indicates that the service rate

for the process control must be greater than

the drift rates for a product at any stages.

Constraint

(14) gives upper bound on the

batch sizes. The lower bound on the batch

sizes is represented by constraint (15).

2.3.5. Number of kanbam

required

The number of kanbans

estimated [2] by

required

(Dl(l + Pii)>,

Yij

=

~~ij

X

can be

(16)

qij)

where ‘I’iJ is the total number of kanbans required, pij the safety coefficient, and U],j= the

container capacity. Here, the values of ~ij and

V]ijare assumed to be deterministic and known.

I3bij

-

Aij+

11

<Dij

(12)

&j,

Qijd Dij,

3. An example

A four stage JIT production

system manufacturing

three products

is considered

to

explain the application of the model. The objective here is to determine the optimal batch

sizes and the kanbans required by minimizing

the total system cost. The input to the example

problem is presented in Table 1. The value of

sij has been determined

here arbitrarily.

But

usually, this value is determined

based on

economical and technical considerations.

The

resulting total system cost, eq. (12) is of nonlinear nature and, hence, the conventional

optimization technique may not be suitable for

the objective function (Z). Therefore, a direct

pattern search method (DPSM) is used for this

purpose [21].

i=l

Subject to:

>

for all i and j.

Problem formulation

Now the problem of lot-sizing in JIT is to

determine

the optimal batch sizes for each

product at each stage which would lead to

a minimum total system cost. This total system

cost can be obtained by the summation of the

cost equations (l), (8). and (11). The formulation of the lot-sizing problem can be given as

Bij

Qij 3 di,

535

4. Analysis of the results

for all i and j,

(13)

for all i and j,

(14)

The results obtained by the DPSM are presented in Table 2. The results corresponding

to

the cases with and without process control

A. Gunasekaran

et al.iDetermning

economic

incentory policies

(quality at the source) are compared in Table 3.

The results of the sensitivity analysis are provided in Table 4.

4.1. Optimul results obtuined b?) the model

The functioning of the DPSM is illustrated

in Table 2. The direct pattern search method

starts from some initial values (i.e., uniform

batch sizes for each product at all stages) for

the decision variables, i.e., the batch size required (Qij) for each product at each stage.

Also, the model considers the batch splitting

and forming in order to achieve both balancing the production

rates and minimum total

system cost. The optimal batch sizes obtained

from the model leads to a savings in total

system cost of about 54% as compared to the

uniform batch sizes. Also, the cumulative imbalance in production

rates has come down

from 10.7365 to 0.2747. Table 2 also presents

the savings in the cost due to imbalance in

production

rates (from $644191 to $16481).

4.2. Comparison

process control

of the results without and with

The optimal batch sizes and the corresponding costs obtained for the cases with and without process control are presented in Table 3.

The quality at the source concept which embodies the process control results in a significant

savings in the scrappage of items and in turn

its associated costs such as investment in materials, labour, and products. Also, the reduction in scrappage leads to an increase in the

utilization level of the facilities.

The optimal batch sizes obtained with process control facilitate the use of smaller batch

sizes as compared to those of without process

control. Also, they lead to an effective balancing of production

rates as compared

to the

larger batch sizes in the case of without process

control.

4.3. Sensitivity

unulysis

To study the behaviour

of the model, a

sensitivity analysis has been conducted.

The

556.

400,

278.

593,

533,

853,

556,

593,

266,

556,

400,

291.

500,

400,

300.

500,

600,

800.

842,

593,

533,

854.

300,

700,

400,

600,

500.

400,

500,

546,

400.

300,

500,

400,

300.

500,

187,

100,

299.

300,

183,

100,

312,

100,

188,

200,

100,

300,

300.

200,

100,

400,

300,

500,

Batch sizes

(Q,, j = 1, N; i = 1. M)

260,

171.

569

569

260.

171,

593

184,

248.

300,

200,

500

500

400,

300,

400,

300,

500

by the search method

32.3096

32.1347

32.1262

30.2348

30.2625

41.1375

Cost due to process

control ($ x10”)

126.2233)] xl00 = 54.82%.

23.0670

23.2702

22.9882

23. I667

23.1690

20.6667

Set-up cost

($ xlO1)

Savings in total system cost = [(126.2233-57.0247),

403

378

328

68

21

1

Iteration

Table 2

The results obtained

1.6481

2.3518

4.8288

16.5968

41.7778

64.4191

Cost due imbalance

in production

rates ($ x 104)

57.0247

57.7567

59.9432

69.9983

95.2093

126.2233

Total cost (Z)

($ xlOS)

0.2747

0.3920

0.8048

2.7661

6.9630

10.7365

Actual imbalance in

production (batchesi’

unit time)

:.

‘)

5’

:

5

G

%

2.

=:

2

2.

3.

2

2

s

e

b

2

+

Q

T

E,

k

e

f

R

187,

100,

299,

260,

171,

569

A = 2.0.4

N = 0.20

533

853,

597,

625,

400,

290,

400,

278.

625,

400,

296,

625,

400,

290,

533,

853,

597,

533,

862.

597,

533,

8.53.

H = 0.10

556,

593,

H = 0.30

200,

100,

313.

100,

299,

200,

100.

319,

200,

100,

313,

f87,

Optimal batch sizes

(Q,,,j = 1, N; i = 1, M)

Parameters!

Variables

278,

171.

594.

171,

569.

278,

171,

597.

278,

171,

594.

260,

Table 4

Results obtained by the sensitivity analysis

556,

400,

278,

36.643 1,

22 3000

22.1736

23.0670

Set-up cost

($ XlOj)

23.0670

593,

533.

853.

with process

control

345,

300,

500

18.0797

302.

100,

300,

1094,

800,

997,

Without

process control

694,

500,

625,

Set-up cost

(S xlOA’)

Optimal batch sizes

(Q,], j = 1, N: i = 1, M)

Situation

Table 3

Comparison of the results without and with process control

38.2924

22.4 169

11.2977

32.3096

Cost due to

process control

(S xlO1)

32.3096

~.OO~

Cost due to

process control

(S xlOS)

4.8885

2.0880

1.6481

Cost due imbalance

in production

rates ($ x 10”)

1.64806

41.5190

Cost due to imbalance

m production rates

($ x104)

79.8240

46.7454

35.5593

51.0247

Total cost (2)

($ XlOj)

57.0241

59.5987

Total cost (2)

(S x10”)

0.8148

0.3381

0.3480

0.2741

Actual imbalance m

productton (batches,

unit time)

0.2747

6.9198

Actual imbalance in

production (batches,

unit time)

B

Z

c;

E

0.

5’

2

5

.;

l.Oa

/I = 4.op

b = 2.08

/? = 1.og

D = 2.OD

D = 0.5D

D = l.OD

a = 0.25~

5( = 0.5ct

cl =

A = OSA

A = 1.OA

556,

400,

278,

556,

400,

290,

556,

400,

253.

556,

400,

278,

625,

479,

520,

654,

547,

927,

593,

533,

853,

797,

647,

897,

1424,

1263,

1525,

556,

400,

278,

625,

479,

520,

654,

547,

927,

593,

533,

853,

791,

647,

897,

1424,

1263,

1525,

593,

533

853,

593,

533

853,

593,

533

853,

556,

400,

278,

455,

400,

278,

593,

533

853,

485,

533

853,

187,

100,

299,

200,

100,

294,

208,

113,

486,

187,

100,

299,

187,

100,

312,

187,

100,

273,

187,

100,

299,

200,

100,

294,

208,

113,

486,

187,

100,

299,

165,

100,

299,

260,

171,

569.

231.

214,

504.

234,

318,

824.

260,

171,

569.

260,

171,

598

260,

171,

512

260,

171,

569.

231,

274,

504.

234,

318,

824.

260.

171,

569

229,

171,

569

15.6429

20.6624

23.0670

47.4958

11.3905

23.0670,

15.6429

20.6624

23.0670

12.1178

23.0670

3.4748

6.0495

32.3096

61.0853

16.5638

32.3096

3.4748

6.0495

32.3096

31.2539

32.3096

20.4191

30.4490

1.6481

2.9897

1.1409

1.6481

20.4191

30.4490

1.6481

3.1958

1.6481

39.5368

57.1609

57.0241

111.5708

29.0952

51.0241

39.5368

57.1609

57.0247

46.5675

51.0241

3.4032

5.0748

0.2747

0.4983

0.1901

0.2741

3.4032

5.0748

0.2141

0.5326

0.2747

details of the results obtained

for different

levels of inventory holding rate (H), mean drift

rate (‘XX).

demand rate (D), and process control

rate (p) are reported in Table 4.

The variation

in inventory

holding rate

leads to significant changes in the cost due to

process control and set-up cost. For instance,

lowering the inventory holding rate (H) from

0.30 to 0.10 results in a reduction in set-up cost

($230670 to $221736). This indicates that the

model selects larger batch sizes when H = 0.10

compared to those of when H = 0.30 in order

to save some set-up cost. Because of the larger

batch sizes, the cost due to cumulative imbalance in production

rates has risen sharply.

This has been revealed

by the increased

level of cumulative imbalance from 0.2747 to

0.3480.

A decrease in set-up cost per set-up ( l.OA to

OSA) may lead to a substantial

reduction in

the total

set-up

cost (from $230670

to

$121178). Owing to the reduction

in set-up

cost, the model selects smaller batch sizes. This

obviously results in a lower cost due to process

control when A is at 0.5A ($323096 to $3 12539)

as compared to that of l.OA. Corresponding

to

this, the cost due to imbalance in production

rates has increased from $1648 1 to $3 1958.

This implies that the model looks for higher

savings in set-up cost when A is equal to 0.5.4.

Under these circumstances, the increase in cost

due to the imbalance in production

rates may

not be significant as compared to the savings

in total set-up cost. Hence, the model prefers

smaller batches to achieve a reasonable reduction in cost due to process control.

A reduction in the average drift rate (1.0~ to

0.5~~)will allow the model to select larger batch

sizes. This perhaps results in a lower total

set-up cost ($230670 to $206624). Obviously,

the reduction in drift rate leads to a corresponding reduction in cost due to process control, from $323096 to $60495. However, the

increase in batch sizes causes problems for

balancing

the production

rates among the

stages. This can be noticed from the increase in

cost due to imbalance

in production

rates

($1648 1 to $304490). This indicates the influence of the process control.

Table 5

Number of kanbans

Stage

Number

of kanbans

product

1

I

7

7

7

8

X

__-

;

4

required for the data given m Table 1

reqmred

product

5

5

5

5

2

(TNK)

product

3

13

13

I2

12

The optimal batch sizes obtained for different levels of demand (1 .OD, 0.5D, and 2.00) are

also presented in Table 4. The analysis of the

results reveals the significance of the optimal

batch sizes and the capacity

available

in

achieving the balancing of production

rates.

Also. the results corresponding

to different

levels of fls are presented in order to gain more

insights into the characteristics

and application of the model. The number of kanbans

required corresponds

to the safety coefficient

value of 0.20 and constant container capacity

of 200 for all the products and at all stages are

presented in Table 5.

5. Discussion on the model and results

The main purpose of our modelling effort is

to explain the relationship

between lot-sizing

policies, quality at the source (process control),

and balancing of production

in a JIT production system. Moreover,

it motivates the lotsizing policies which are based on batch

splitting and forming with a view to attain the

balancing among the production

rates. The

proposed model is a planning model and it

helps to derive overall ideas about the batching policies wherein the set-up cost is quite

accountable as compared to the inventory cost

due to process control and imbalance in production rates. Nevertheless,

there are many

other operational,

and process constraints

such as material handling capcity, capacity of

the machines, various priority

rules in sequencing and scheduling, etc. are to be considered in the batch size optimization.

A. Gunasekaran

et al.,‘Drterrnining

The results obtained

indicate the significance of process control which rather supports

the quality at the source as noted earlier. The

assumptions

that the drifts rates follow

Poisson and the service time follows exponential require further investigation

in order to

confirm the application

with real life JIT

situations. Besides, a reduction in set-up cost

demonstrates

the potential in achieving the

balancing among the production stages. In addition to this, investing in quality control leads

to a significant improvement

in achieving the

JIT material flow. Furthermore,

various insights could be derived from the model for

different production situations on different related issues like investing in quality control,

set-up reduction programme, process control,

etc., and their implications on the performance

of the JIT system. The trade-off between the

value of the scrap and the cost related to process control would be an interesting problem

to pursue in future. The study reported here

may be useful for a time-phased implementation of JIT in manufacturing

organizations.

6. Conclusions

A mathematical

model has been developed

for determining economic production quantities in JIT manufacturing

systems by minimizing the total system cost. The main objective of

the model is to determine the optimal batch

sizes incorporating

the process control so that

there is a smooth material flow among the

stages that support the JIT production. A direct pattern search method has been employed

for determining

the economic

production

quantities. However, the model developed is

based on a number of assumptions

and approximations.

This implies that there are avenues for further investigation

to enhance the

accuracy of modelling the JIT systems.

Acknowledgements

The authors

Meester

and

are grateful to Professors G.J.

John Miltenberg,

and three

economic

rnrrrrtor~ policies

541

anonymous referees for their extremely useful

and helpful comments on the earlier version of

this manuscript. Also, the authors thank Professor Ilkka Virtanen, Rector, University

of

Vaasa, Finland, for his extended co-operation

in their research projects.

References

R.. 1982. Japanese

Manufacturing

Cl1 Schonberger.

Techniques. Free Press, New York.

F.C. and Uchikawa, S..

CA Sugimori, Y.. Kasunokt.

1977. Toyota production

system and kanban system. materialization

of just-in-time and respect for

human system. Int. J. Prod. Res., 15(6): 5533564.

A.. Goyal, S.K., Martikainen, T. and

c31 Gunasekaran.

Yli-Olli, P. 1991. Modelling and analysis of JIT

concepts: A review. Working

Paper. School of

Business Studies. University of Vaasa. Vaasa.

P.R., Rees, L.P., Taylor, B.W. and

c41 Philipoom.

Huang, P.Y., 1987. An investigation

of the factors

influencmg the number of kanbans required in the

implementation

of the JIT technique with kanbans.

Int. J. Prod. Res., 25(3): 457-472.

P.R., Rees. L.P.. Taylor, B.W. and

CSI Philipoom.

Huang. P.Y., 1990. A mathematical

programming

approach for determining

work-centre

lot-sizes in

a just-in-time

systems with signal kanbans. Int. J.

Prod. Res.. 28: 1-15.

C61 Spence, A.M. and Porteus. E.L., 1987. Set-up reduction and increased effective capacity. Manage. Sci..

33(10): 1291-1301.

c71 Zangwill. W.I., 1987. From EOQ towards ZI. Manage. Sci., 33( 10): 120991223.

PI Porteus, E.. 1985. Investing in reduced set-ups in

the EOQ model. Manage. Sci.. 31: 998-1010.

E.. 1986 Investing

in new parameter

c91 Porteus.

values in the discounted

EOQ model. Naval Research Logistics Quarterly. 34: 39-48.

Cl01 Porteus. E.. 1986. Optimal lot-sizing, process quality improvement

and set-up cost reduction, Oper.

Res., 34: 137-144.

of inventory cost

Cl 11 Funk. J.L.. 1989. A comparison

reduction strategies m a JIT manufacturing

system.

Int. J. Prod. Res., 27(7): 1965-1080.

the

Cl21 Bard. J.F. and Golany, B., 1991. Determining

number of kanbans in a multi-product.

multi-stage

production

system.

Int. J. Prod.

Res., 29(5):

881-895.

Cl31 Sipper, D. and Shapira, R. 1989. JIT versus WIP

- a trade-off analysis. Int. J. Prod. Res., 27(6):

90339 14.

Cl41 Karmarkar, U.S , 1986. Push, pull and hybrid control systems. Working Paper Series No. QM 8614.

Graduate School of Business Administration,

University of Rochester, Rochester.

[ 151 Karmarkar, U.S. and Kekre, S.. 1989. Batching policy

in kanban systems. J. Manufac. Sys., 8(4): 317-328.

[16] Bitran. G.R. and Chang, L., 1987. A mathematical

programming

approach to a deterministic

kanban

system. Manage. Sci.. 29( 10): 427-441.

[17] Axsiter, S. and Rosling. K., 1990. Installation

versus Echelon stock polictes for multi-level inventory

control. Research Report. Linkoping Institute of

Technology, Linkiiping.

[ 181 Gunasekaran,

A., Goyal. S.K.. Martikainen, T. and

Yh-Olli, P., 1992. Equipment selection problems in

Just-in-time

manufacturing

systems. J. Oper. Res.

Sot. (Forthcommg).

[19] Panico, J.A.. 1963. Queuemg

Theory. PrenticeHall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.

[?O] Goyal, S.K. and Gunasekaran,

A., 1990. Effect of

dynamic process quality control on the economics

of production.

Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manage., lO(7):

69977.

1311 Hooke, R. and Jeeves, T.A., 1966. Direct search of

numerical and statistical problems. J. Assoc. Comp.

Mach.. 8: 212-229.