Contact author: Rene R. Rocha Assistant Professor Department of Political Science

advertisement

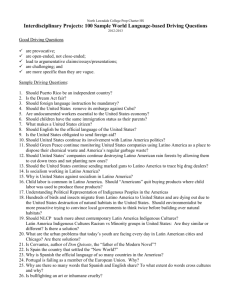

“Ethnic Context and Immigration Policy Preferences among Latinos and Anglos” Contact author: Rene R. Rocha Assistant Professor Department of Political Science The University of Iowa 341 Schaeffer Hall Iowa City, Iowa 52242 (319) 335-2528 rene-rocha@uiowa.edu Thomas Longoria Texas Tech University Robert D. Wrinkle University of Texas, Pan American Benjamin R. Knoll Centre College Jerry L. Polinard University of Texas, Pan American James Wenzel University of Texas, Pan American Abstract Objective. We examine how the immigration policy preferences of Anglos and Latinos vary according to ethnic context. Specifically, we hypothesize that immigration policy attitudes are a product of both Latino immigrant and Latino native-born group size. In contrast to previous work which found that Latinos and Anglos react to contextual forces in an identical manner, we argue that Latino group size produces opposite reactions for Anglos and Latinos. Methods. These hypotheses are tested using an original state-wide survey of Anglos and Latinos in Texas conducted during 2006 which is supplemented with data from the 2000 census. Results. Our findings show that residing in a heavily Latino area produces more liberal immigration attitudes among Latinos and more conservative attitudes among Anglos. However, this result is driven not by the size of the foreign-born Latino population, but rather the size of the native-born Latino population. Conclusion. Anti-immigrant sentiments among Anglos appear to result, at least in part, from ethnic concerns. CITATION: Rene R. Rocha, Thomas Longoria, Robert D. Wrinkle, Benjamin R. Knoll, J.L. Polinard, and James P. Wenzel. 2011. “Ethnic Context and Immigration Policy Preferences among Latinos and Anglos.” Forthcoming: Social Science Quarterly. 1 “Ethnic Context and Immigration Policy Preferences among Latinos and Anglos” Immigration policy has emerged as a salient issue in American political discourse over the past several years. Even with the endorsement and strong backing of President George W. Bush, the U.S. Congress failed twice in as many years (2006 and 2007) to come to a compromise on proposed immigration reform measures. Immigration reform also turned out to be a significant issue in the 2008 presidential primary campaign, although it was eclipsed by the economic crisis during the 2008 general election campaign. With the recent passage of SB1070 in Arizona in 2010, immigration reform has again been placed on the national political agenda. Thus, research investigating the determinants of attitudes toward immigration policy is not only timely and relevant, but also gives scholars an excellent opportunity to further investigate how individual attitudes on salient issues are shaped by environmental factors. Specifically, this study seeks to more fully explore how racial/ethnic context determines attitudes toward immigration policy. We hypothesize that attitudes toward immigration are a product of both Latino immigrant as well as native-born group size. We argue that Latinos tend to react to the presence of a large foreign-born population in a manner opposite to that of Anglos. This differing expectation is derived from Bledsoe, et al.‟s (1995) argument that increased spatial density among African Americans results in increased levels of racial solidarity. Adapting this argument to Latinos, we submit that as the geographic concentration of foreign-born and nativeborn Latinos increases, Latinos will become more supportive of liberal immigration policies. This hypothesis stands in contrast to previous studies which found that Latinos and Anglos react to contexts in an identical manner, i.e. becoming more anti-immigrant in high Latino density areas (see Hood, Morris, and Shirkey 1997 and Hood and Morris 1998). 2 These hypotheses are tested using an original state-wide survey of Anglos and Latinos in Texas conducted in 2006, supplemented with contextual data gathered from the 2000 Census. The results of this analysis confirm our hypotheses and indicate that residing in areas with higher Latino populations (specifically populations comprised primarily of native-born Latinos, but not undocumented Latino immigrants) produces more liberal immigration attitudes among Latinos and more conservative attitudes among Anglos. This finding suggests a change in racial/ethnic dynamics surrounding immigration policy attitudes in Texas and also suggests repercussions nationally. Ethnic Context and Anglo Attitudes toward Immigration Policy Attitudes toward immigration have long been thought to be a product of individual-level characteristics such as ideology, age, gender, education, and economic vulnerability (Binder, Polinard, and Wrinkle 1997, Citrin, et al. 1997). However, scholars have also hypothesized that the racial/ethnic context in which a person lives is a key determinant of attitudes toward immigration. Indeed, social scientists have long speculated that racial attitudes and public policy preferences are at least partially a product of the residential environments in which individuals find themselves. The link between social context and policy preferences can perhaps best be explained through social identity theory (Tajfel and Turner 1986) which posits that human beings are psychologically hard-wired to automatically sort the world into “in-groups” and “out-groups.” Since race is a salient physical characteristic, the formation of strong in-group/out-group distinctions based on racial differences is relatively effortless and therefore very common. Social identity theory further hypothesizes that an individual‟s identity and sense of selfworth are partially dependent upon the perceived favorability of his or her in-group identity. 3 Thus, individuals are highly motivated to maintain a strong and positive in-group evaluation. Since in-group identities can only be formed in comparison with relevant out-groups, however, individuals are also motivated to maintain a proportionally strong and negative evaluation of outgroups. It follows that as the size of the relevant out-group increases, the proportional size of the in-group decreases. In turn, this threatens the dominant status of the in-group and thus also threatens the perceived value of the in-group identity. Individuals are thus motivated to strengthen their negative out-group evaluation which manifests itself in punishing behavior, specifically by not supporting political policies that could potentially benefit members of the outgroup (see Tajfel 1970, e.g.). These social-psychological effects are manifested in specific theoretical mechanisms through which residential environments are thought to influence attitudes and policy preferences. The first of these is the power-threat hypothesis (also known as the “racial threat” hypothesis). In its simplest form, the hypothesis suggests that “a superordinate group (e.g. whites) becomes more racially hostile as the size of the proximate subordinate group increases, which punitively threatens the former‟s economic and social privilege” (Oliver and Wong 2003). In other words, as the size of the racial minority group in an individual‟s area increases, he or she will feel threatened and respond by engaging in punishing behavior as manifested in lowering or withdrawing support for pro-minority public policies. The contention that racial attitudes and policy preferences vary in accordance with the size of the minority population within a given geographical unit has grown largely out of an observation made in Southern Politics where Key ([1949] 1984) observes that counties with substantial African-American populations were also the ones in which conservative gubernatorial candidates enjoyed the most support. Key‟s initial observation was advanced, although 4 sometimes in a modified form, by other scholars of the era (e.g. Keech 1968). Since that time, several works have provided a plethora of empirical evidence for the power-threat hypothesis (e.g. Giles 1977; Giles and Buckner 1993; Glaser 1994; Tolbert and Grummel 2003).1 In contrast, scholars of racial and ethnic politics have provided a significant amount of empirical evidence for the notion that racial attitudes are a product of direct contact with minority group members (Aberbach and Walker 1973; Ellison and Powers 1994; Meer and Feedman 1966; Schuman and Hatchett 1974; Tsukashima and Montero 1976; Williams 1964; Sigelman and Welch 1993; Welch and Sigelman 2000). This social contact hypothesis argues that increased interracial contact makes it difficult for groups to accept typically negative racial stereotypes and also increases the probability of both groups holding shared values (Forbes 1997). The effects of social contact appear to be a robust predictor of racial attitudes among Anglos within the United States, often washing out the effects of sociological variables such as education (Welch et al. 2001). The social contact argument has led some scholars to argue that Anglos are more likely to develop favorable attitudes toward racial/ethnic minorities in areas where minorities make up a large proportion of the population (Voss and Miller 2001). This occurs because contact, while technically an individual-level variable, is greatly influenced by contextual factors. Presumably, areas with large minority populations are also ones in which one would expect Anglos and minorities to come into regular contact, whereas homogenous communities tend not to provide forums for interracial contact. This contact is crucial because, according to social identity theory, increased interaction and contact can eventually break down perceived in-group/out-group barriers and distinctions. As the out-group eventually comes to be considered part of the ingroup, punishing behavior toward minorities is eventually replaced with reward behavior, 5 thereby increasing support for public policies that stand to benefit members of the minority group. Working within this power-threat vs. social contact framework, Hood and Morris (1998) examine how environmental factors influence Anglo attitudes on immigration. They find that Anglos residing in contexts with large illegal immigrant populations tend to possess more negative attitudes regarding immigration, a finding which would seem to support the powerthreat hypothesis. However, they also find that as the relative size of the legal immigrant population increases, Anglos become more supportive of liberal immigration policies. Interestingly, these contextual variables have been found to influence Latino attitudes in a similar manner (Hood, Morris, and Shirkey 1997). Thus, Hood and Morris (1998) do not offer unconditional support for either the powerthreat or social contact hypotheses. They do suggest the presence of another interesting dimension to contextual theories of political behavior. That is, Hood and Morris‟s (1998) work indicates that Anglos react to the presence of certain segments of the Latino population (e.g. legal versus illegal immigrants) differently. Other scholars have suggested that economic heterogeneity within racial/ethnic groups can influence racial attitudes (see Branton and Jones 2005, Gay 2004). Branton and Jones (2005) show that when the disparity between Anglo and minority economic status is large, Anglos tend to react negatively to the presence of a large minority population. As the economic gap between the two groups narrows, however, Anglos may instead respond to minorities favorably, developing more liberal policy preferences. Hood and Morris (1998) suggest that Anglos make distinctions between the minorities based upon social, cultural, or legal considerations. Studies of racial attitudes in the South, where the Latino population is heavily foreign-born, show that Anglos‟ feelings of commonality with Latinos is 6 relatively low, despite the presence of a large black population (McClain, et al. 2006). This is an idea explored relatively less in the literature and forms the basis of our first line of inquiry. According to this approach, one might also suspect that attitudes and policy preferences are influenced by differences within the Latino community based upon nativity. One of the most obvious differences between the African-American and Latino populations within the United States is the heterogeneity of the Latino community which the immigration process produces, specifically native-born vs. foreign-born populations. Indeed, this heterogeneity within the Latino community may be one of the critical factors that highlight the way in which theories of racial context apply differently to Latinos and African-Americans. Failing to account for differences in the Latino population based upon nativity could lead to the misleading conclusion that Anglos are reacting to the presence of all Latinos similarly, regardless of the level of acculturation within the Latino population in their neighborhoods. Accounting for the complexities of the relationship in the racial/ethnic context and political behavior also allows for a better response to critics who argue that the power-threat hypothesis is historically and geographically contingent, applicable only to African-Americans residing within the American South before the onset of the civil rights movement (see Voss 2000). While Hood and Morris (1998) argue that Anglos make distinctions based upon the residential legality of the Latino immigrant population, we are skeptical about the ability of Anglos to easily or accurately discern the legal or illegal status of Latino immigrants. We ask instead whether Anglos react differently to foreign-born versus native-born Latinos. Foreignborn residents tend to generate ethnic enclaves and engage in other practices that make their presence more visible to native-born Latinos and Anglos. Many of these visible manifestations of the growth in the foreign-born Latino population (congregating day laborers, Latino 7 supermarkets, Spanish radio advertisements, etc.) may represent a form of contact as well as threat. The visible presence of an ethnic enclave produces the mechanism for how Anglos and native-born Latinos are able to determine an increase in the foreign-born population as well as form and reinforce impressions of ethnic and racial difference. This also offers a direct test of the argument made by Rocha and Espino (2009) that Anglos react in a manner consistent with the power-threat hypothesis when they reside in contexts that are populated by a substantial number of foreign-born Latinos, but that they do not vary their attitudes toward English language or immigration policies depending upon the size of the native-born Latino population within their area. Ethnic Context and Latino Attitudes toward Immigration Policy With few exceptions (e.g. Gay 2004; Hood, Morris, and Shirkey 1997; Leighley 2001; McClain et al. 2006; Oliver 2001; Welch et al. 2001), most work on the political implications of racial environments is concerned with the political behavior of Anglos. In recent years, this literature has become increasingly interested with the behavior of African-Americans. As we alluded to earlier, Hood, Morris, and Shirkey (1997) find that Latinos tend react to the presence of immigrants in a manner similar to Anglos. This finding, however, is somewhat at odds the spatial density hypothesis proposed by Bledsoe et al. (1995; see also Welch et al. 2001). Bledsoe, et al.‟s (1995) study of racial attitudes in Detroit argues that spatial density works to increase feelings of African-American solidarity. Assuming that this relationship holds for Latinos, high levels of in-group size should work to foster a greater sense of Latino group identity, generating liberal policy preferences regarding immigration instead of the conservative preferences that the power-threat hypothesis would predict Anglos to possess. Likewise, Leighley (2001) argues that minority group size elicits different reactions from Anglos and 8 minorities, the former viewing it as a threat and the later viewing it a signal that political participation can be turned into social and political gains. It remains unclear whether individual Latinos will react to the presence of a large native or foreign-born Latino population in a different manner than Anglos, as suggested by Leighley (2001). Thus, we investigate whether and how local demographic context plays a significant role in the political views and perceptions of Latinos. Data and Methods The data used in this analysis comes from a public opinion survey conducted by the “Survey Research Center” at Texas Tech University. This survey was in the field during the summer of 2006 and sampled respondents living in Texas. Similar forms of the questionnaire were administered to a statewide random sample (random digit dialing) of Latinos and Anglos in Texas with a Latino oversample from border counties.2 Both studies used the same instrument and the Spanish translations for those conducted in Spanish were done by native Spanish speakers. Latinos comprised 45% of our final sample (N=252), while Anglos comprised 55% of all respondents (N=362). While this is a single state study, we believe that it speaks to the issue of immigration in a significant manner because Texas has the third largest immigrant population in the United States, ranking only behind New York and California, as well as its status as a prominent border state. We are primarily interested in the policy-related attitudes of respondents. To that end, we estimate a series of models using three policy-related questions as dependent variables. We attempt to capture different elements of immigration policy with these variables.3 These questions are: 9 1) Do illegal immigrants help or hurt the U. S. economy? (Help the economy by providing low-cost labor, Hurt the economy by driving wages down) 2) Should the number of new legal immigrants be increased or decreased? (Increased a lot, Increased a little, Neither increased or decreased, Decreased a Little, Decreased a Lot) 3) Do you agree or disagree with the building of a fence along the U.S.-Mexico border? (Strongly Agree, Agree, Neither Agree or Disagree, Disagree, Strongly Disagree) Table 1 contains a summary of descriptive statistics for each of these variables. Question 1 is a binomial variable and Questions 2 and 3 are 5-point ordinal variables. Each variable is coded so that higher values correspond with more liberal preferences. Appendix A contains full question wordings of the key variables employed in this analysis. This original survey of Anglos and Latinos residing in Texas is supplemented with contextual data gathered from the 2000 U.S. Census. Specifically, we obtained the percentage of Latino residents within each respondent‟s county. Respondents within our sample reside in counties where the Latino population is as small as 2% and as large as 98%. Respondents are drawn from 53 counties in total. Urban counties are represented nearly proportionally within the data. For example, 13% of respondents reside in Harris County where 11% of the state‟s population is located. The Census Bureau also provides data on the percentage of foreign- and native-born Latinos at the county level, allowing us to test the argument that Anglos react differently to distinct segments of the Latino population. It is important to note that while the Texas shares a border with Mexico, not all areas of Texas are immigrant-receiving communities. This variation in terms of immigrant context (e.g. communities with similar Latino population percentages but with differing proportions of foreign- and native-born Latinos) is essential for 10 our analysis. The percentage of foreign-born Latinos varies from 1% to 37% in our data.4 (See Table 1 for descriptive summary statistics). Another important variable we must account for is the structural pattern of residence between Latinos and Anglos. The conflict between the power-threat and social contact hypothesis is predicated upon the assumption that increased group size leads to more interracial contact. This assumption is tenuous in highly segregated areas. Therefore, we control for the level of Anglo-Latino segregation within each respondent‟s Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area.5 In order to measure the structural pattern of residence between Anglos and Latinos, we use a statistic, known as the Dissimilarity Index, long used by demographers to measure levels of segregation in an area. This index, taken from the Lewis Mumford Center for Comparative Urban and Regional Research at SUNY-Albany, measures whether one racial group is distributed across census tracts in an area the same way as another racial group. The Mumford Center also provides distinct measures that capture the level of segregation between Anglos, native-born Latinos, and foreign-born Latinos. When examining which Anglos react specifically to the presence of native- or foreign-born Latinos, we use the corresponding dissimilarity index as a control variable. We further include additional control variables measuring individual-level characteristics that have been shown to shape attitudes toward immigration policy. These include standard socio-economic and demographic controls such as household income, sex, and education (Binder, Polinard, and Wrinkle 1997). In addition, we control for individual partisan affiliation and approval of President Bush. Lastly, we control for respondents‟ religious affiliation by including a control for Roman Catholic religious affiliation. Aside from the fact that many 11 Latinos are Catholic, previous research has shown that members of minority religions are more likely to feel empathy for, and thus more supportive of, policies that favor racial and ethnic minorities (see Fetzer 1998 and Knoll 2009). Additionally, prominent cardinals of the Catholic Church publicly supported the liberal immigration reform measures proposed by the Senate in 2006 and 2007. The Catholic Church also played a significant role in the mobilization of Latinos in opposition to punitive immigration reform measures during this same period (see Pomfret 2006). While we expect Anglos to prefer more restrictive immigration policies, general status may impact levels of support for liberal policies among Latinos. Specifically, native-born Latinos may be less likely to support liberal immigration policies than their foreign-born counterparts. It is also possible that native-born Latinos react to ethnic context in a distinct manner. In short, accounting for in-group heterogeneity if critical when studying Latino attitudes as well as those held by Anglos. Unfortunately, only a trivial number of non-Latinos or nonAnglos were sampled (30 blacks, 3 Asian-Americans, and 6 American Indians). Due to this small sample size, these groups are excluded from the study. Findings Descriptive statistics for our dependent variables and our key contextual measures are presented in Table 1. Before presenting our full models, we attempted to determine whether Anglos and Latinos held distinct preferences regarding immigration policies without accounting for ethnic context. Our analysis (results not shown but available from the authors) shows that Anglos are generally more likely than Latinos to express anti-immigrant sentiments.6 In fact, ethnicity is the only variable to predict each of the three dependent variables used in our analysis. Native-born Latinos are no more or less likely than the foreign-born to believe the number of 12 legal immigrants allowed into the US should be increased. However, the native-born are less likely to believe that immigration has a positive economic impact and are less likely to oppose the construction of a border fence. Catholics are significantly more likely to believe that illegal immigrants help the U.S. economy and oppose the construction of a border fence. Highly educated respondents tend to feel that the number of legal immigrants allowed into the U.S. should be increased. [Table 1 About Here] Table 2 presents the findings for second series of models, which account for contextual forces.7 For each of these models, standard errors are clustered by county.8 In this analysis, we test to see whether the percentage of Latinos (total native-born and foreign-born) within each respondent‟s county influences their policy views, controlling for individual-level characteristics. While our contextual measures are fairly robust predictors of respondents‟ opinions, most of the individual-level variables fail to consistently predict attitudes on immigration. In fact, no individual-level variable is significant across all three of our dependent variables. [Table 2 About Here] Table 2 offers evidence for the contention that the size of the total Latino population is a partial determinant of immigration attitudes. Unlike Hood, Morris, and Shirkey (1997) who found that Latinos react to contextual variables in the same way as Anglos, our evidence suggests that Latinos react in a dissimilar manner. That is, Anglos residing in contexts with a large Latino population are more likely to develop restrictionist attitudes, while Latinos residing in contexts with a large Latino population are more likely to develop liberal feelings toward immigration. This result offers further support of the power-threat hypothesis within the context of immigration politics and may be viewed as similar to Bledsoe et al.‟s (1995) assertion that 13 African-American solidarity increases in areas of high in-group exposure. The influence of racial/ethnic context on levels of immigration attitudes also appears to be quite robust, with Latino population size proving a significant predictor across all three of our dependent variables. One contextual measure, the level of residential segregation between the Anglo and Latino populations, appears to be the only influence on attitudes regarding increasing legal immigration (p-value = .08). Contrary to our expectations, respondents are more likely to favor increasing the number of legal immigrants in more segregated areas. In order to illustrate the substantive impact of racial/ethnic context, Table 3 presents a series of predicted probabilities. We see that the probability of an Anglo respondent who lives an area with few Latinos (2%) agreeing with the idea that immigration has positive economic consequences is relatively high (.45). An Anglo residing in a predominately Latino area (94% Latino) is much less likely to hold this belief (predicated probability of agreement = .27). The opposite is true for Latinos. Latinos residing in areas where few other Latinos live (2%) are less likely to believe that immigration has positive economic consequences than those who live in heavily Latino areas. Note that native-born Latinos living in predominately non-Latino counties are actually less likely than Anglos to believe that immigration has positive economic consequences. Unlike Anglos, native-born Latinos respond positively to the presence of Latinos and tend to view immigration favorably in heavily Latinos areas.9 [Table 3 About Here] We see a similar pattern regarding the predicted probability that Anglo or Latino respondents will believe that the number of legal immigrants allowed into the U.S. should be increased. The preferences of Anglos and Latinos (both native and foreign-born) are virtually identical in predominately non-Latino areas. In heavily Latino areas, however, Anglo and Latino 14 preferences diverge by a substantial margin. The probability that a native or foreign-born Latino will believe that the number of legal immigrants allowed into the US should be increased in a county that is 94% Latino is approximately .50. The probability that an Anglo respondent residing in the same context will express the same position is .05. Lastly, we turn to the probability that a respondent will oppose the construction of fence along the US-Mexican border. Once again, attitudes among Anglos and foreign-born Latinos are indistinguishable in predominately non-Latino counties. In such contexts, native-born Latinos are actually the least likely to oppose the construction of a border fence. As Latinos make up a larger proportion of the population, native and foreign-born Latinos are more likely to oppose construction, while Anglos are less likely to do the same. Figure 1 shows the marginal effect of our interaction term on responses regarding the economic impact of immigration. The figure shows the derivate of the index of our dependent variable. Again, we see that Anglo attitudes do not differ from those of Latinos in non-Latino areas. As an area becomes increasingly populated by Latinos, Anglo preferences diverge. [Figure 1 About Here] Next we turn to the hypothesis posed by scholars that Anglos make distinctions between certain segments of the Latino population when reacting to contextual forces. The results demonstrate the Anglos do react differently to foreign and native-born Latinos, but in a manner opposite to that suggested by Rocha and Espino (2009). In Table 2, where we accounted for the percentage of Latinos within a respondent‟s area without concern as to their nativity, our contextual measures predicted immigration attitudes across each of our dependent variables. However, for only one of our three indicators (belief that the number of legal immigrants should 15 be increased) do we find evidence of contextual effects when limiting our analysis to the impact of foreign-born Latinos. We also included an interaction term between our “native-born” variable and the size of the Latino foreign-born population (results not shown but available from the authors). The inclusion if this term proved to be insignificant. We take this as evidence that Latinos are generally more supportive of liberal immigration policies in areas of high in-group size, although the base level of liberalism is lower for native born Latinos. [Table 4 About Here] The null results presented in Table 4 would imply that our previous findings are being driven by reactions to the presence of native-born Latinos. Indeed, Table 5 shows that the presence of native-born Latinos within a respondent‟s area successfully predicts immigration attitudes in a manner consist with the results produced in Table 2. This stands in direct contrast to Rocha and Espino (2009) who argue that the presence of native-born Latinos does not influence Anglo preferences on immigration policy. The presence of native-born Latinos, at least in our sample of Texas residents, does matter, perhaps more so than the presence of foreign-born Latinos. [Table 5 About Here] Some findings do vary across the three dependent variables and these distinctions shed additional light on the impact of population context and attitudes. Using three questions demonstrates that immigration policy attitudes are multidimensional. A Catholic respondent, for example, is more likely to express a view that immigrants help the economy and oppose a border fence but not more likely to report support for increasing legal immigration. We suspect that this is due to the influence of the Catholic Church‟s teachings on the rights of immigrants and affinity 16 for fellow Catholics to the extent that they are less likely to differentiate legal from illegal immigration. Self-reported membership in the Republican Party is only a statistically significant predictor of attitudes toward the border fence but not of the other dependent variables. Republican respondents in Texas may be more influenced by the national rhetoric surrounding the border fence than Democrats. Republicans also tend to be located in non-border areas whereas Democrats in Texas are more likely to be from the border region. We also find that education is a statistically significant predictor of support for increased legal immigration across all four models and that education is not a statistically predictor of the other dependent variables. Those respondents with higher levels of education may be more willing to accept a pluralistic America. Conclusion This study has extended previous research investigating the impact of ethnic context on individual attitudes toward racial public policies. We hypothesized that immigration policy attitudes are influenced by the size of the native-born and/or foreign-born Latino population in an individual‟s county. We further hypothesized that Anglos and Latinos form immigration-related policy preferences differently based on the ethnic context in which they live. Our results suggest that Anglos residing in areas with a higher proportion of Latinos are more likely to have restrictionist immigration policy preferences and that Latinos in these same areas are more likely to have liberal immigration policy preferences. We further found that this result is not driven by the size of the foreign-born Latino population, but rather by the size of the native-born Latino population. This finding does not necessarily disconfirm previous work, but does suggest a change in ethnic dynamics surrounding immigration policy in Texas and possibly nation-wide as well. 17 The finding that higher levels of native-born Latinos in an area produce more liberal policy preferences among Latinos demonstrates that Bledsoe, et al.‟s (1995) finding that spatial density contributes to solidarity among African-Americans in Detroit also holds for Latinos in Texas. Again, racial/ethnic context matters in shaping policy preferences. This suggests that Latinos surrounded by fellow Latinos (in this case, native-born Latinos) are more likely to extend their in-group circle to include other foreign-born Latinos and consequently favor more liberal immigration policies. Furthermore, the results of this study are important for the implications they have on the current public debate regarding immigration policy. Those in favor of more “hard-line” immigration approaches often cite the importance of following proper immigration procedures as well as the risk of terrorists sneaking over the U.S.-Mexican border, while eschewing the suggestion that these attitudes are motivated by culturally nativist or ethnic-based factors. These results, however, demonstrate that anti-immigration sentiment is largely a product of the size of the native-born Latino population, but not the foreign-born Latino population. We conclude, therefore, that racial- or ethnic-based concerns may trump worries about legal procedures or national security when it comes to the formation of immigration policy attitudes. Future studies could build upon on the findings presented herein by extending this analysis to the nation as a whole and/or investigating the effect of native-born Latino population size on the issue preferences of other racial groups such as African-Americans or AsianAmericans. Examining other geographic areas would also allow researchers to consider how relationships might vary for other Latino sub-groups or in areas where the Latino population is more heterogeneous in terms of national origin. 85% of Latinos in Texas are of Mexican origin, allowing us little leverage on this question. It is possible that the way in which Anglos react to 18 ethnic context is contingent upon the national origin of the nearby Latino population. Such studies will undoubtedly add to our understanding of this highly salient issue, as well as to our understanding of inter-group attitude formation more generally. 19 References Aberbach, Joel, and Jack Walker. 1973. Race in the City. Boston: Little, Brown. Binder, Norman E., J. L. Polinard and Robert D. Wrinkle. 1997. “Mexican American and Anglo Attitudes Toward Reform.” Social Science Quarterly 781: 324-337. Blau, Peter M., Terry C. Blum, and Joseph E. Schwartz. 1982. “Heterogeneity and Intermarriage.” American Sociological Review 47(1): 45-62. Blau, Peter M., Carolyn Beeker, and Kevin M. Fitzpatrick. 1984. “Intersecting Social Affiliations and Intermarriage.” Social Forces 62(3): 585-606. Bledsoe, Timothy, Susan Welch, Lee Sigelman, and Michael Combs. 1995. “Residential Context and Racial Solidarity among African-Americans.” American Journal of Political Science 39: 434-458. Branton, Regina P. and Bradford Jones. 2005. “Values, Context, and Racial and Ethnic Diversity.” American Journal of Political Science 49: 359-372. Branton, Regina, Gavin Dillingham, Johanna Dunaway, and Beth Miller. 2007. “Anglo Voting on Nativist Ballot Initiatives: The Partisan Impact of Spatial Proximity to the U.S.Mexican Border” Social Science Quarterly 88: 882-897. Carmines, Edward G. and James A. Stimson. 1980. “The Two Faces of Issue Voting.” The American Political Science Review 74: 78-91. Citrin, Jack, Donald P. Green, Christopher Muste, and Cara Wong. 1997. “Public opinion toward immigration reform: The role of economic motivations.” The Journal of Politics 59(3):858-881. Ellison, Christopher, and Daniel Powers. 1994. “The Contact Hypothesis and Racial Attitudes among Black Americans.” Social Science Quarterly 75: 385-400. 20 Fetzer, Joel S. 1998. “Religious Minorities and Support for Immigrant Rights in the United States, France, and Germany.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 37: 41-49. Forbes, H. D. 1997. Ethnic Conflict: Commerce, Culture, and the Contact Hypothesis. New Haven: Yale University Press. Gay, Claudine. 2004. “Putting Race in Context: Identifying the Environmental Determinants of Black Racial Attitudes.” American Political Science Review 98: 547-562. Giles, Michael W. 1977. “Percent Black and Racial Hostility: An Old Assumption Reexamined.” Social Science Quarterly 58: 412-17. Giles, Michael, W., and Melanie A. Buckner. 1993. “David Duke and Black Threat: An Old Hypothesis Revisited.” The Journal of Politics 55: 702-713. Glaser, James M. 1994. “Back to the Black Belt: Racial Environment and White Racial Attitudes in the South.” Journal of Politics 56: 21-41. Hood, M.V., and I. L. Morris. 1997. “¿Amigo o Enemigo?: Context, Attitudes, and Anglo Public Opinion Toward Immigration.” Social Science Quarterly 78: 309-323. Hood, M. V., III, Irwin L. Morris, Kurt A. Shirkey. 1997. “„¡Quedate o Vente!‟: Uncovering the Determinants of Hispanic Public Opinion toward Immigration.” Political Research Quarterly 50: 627-647. Keech, William R. 1969. The Impact of Negro Voting: The Role of the Vote in the Quest for Equality. New York: Greenwood Publishing Group. Key, V. O., Jr. 1984 [1949]. Southern Politics in State and Nation. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. Knoll, Benjamin R. 2009. “And Who is My Neighbor? Religion and Immigration Policy Attitudes.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 48: 313-331. 21 Leighley, Jan E. 2001. Strength in Numbers? The Political Mobilization of Racial and Ethnic Minorities. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. McClain, Paula D., Niambi M. Carter, Victoria M. DeFrancesco Soto, Monique L. Lyle, Jeffrey D. Grynaviski, Shayla C. Nunnally, Thomas J. Scotto, J. Alan Kendrick, Gerald F. Lackey and Kendra Davenport Cotton. 2006. “Racial Distancing in a Southern City: Latino Immigrant Views of Black Americans.” Journal of Politics 68: 571-584. Meer, Bernard, and Edward Freedman. 1966. “The Impact of Negro Neighbors on White Homeowners.” Social Forces 54: 900-924. Oliver, J. Eric. 2001. Democracy in Suburbia. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Oliver, J. Eric, and Janelle Wong. 2003. “Intergroup Prejudice in Multiethnic Settings.” American Journal of Political Science 47: 567-82. Pomfret, John. 2006. Cardinal puts church in fight for immigration rights. Washington Post, April 6. Available at http://www.washingtonpost.com/wpdyn/content/article/2006/04/01/AR2006040101206.html. Rocha, Rene R., and Rodolfo Espino. 2009. “Racial Threat, Residential Segregation, and the Policy Attitudes of Anglos.” Political Research Quarterly 62: 415-426. Schuman, Howard, and Shirley Hatchett. 1974. Trends in Racial Attitudes. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Sigelman, Lee and Susan Welch. 1993. “The Contact Hypothesis Revisited: Black-White Interaction and Positive Racial Attitudes.” Social Forces 71: 781-796. Tajfel, Henri. 1970. “Experiments in Intergroup Discrimination.” Scientific American 223(2): 96102. 22 Tajfel, Henri and John C. Turner. 1986. “The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behavior.” In Psychology of Intergroup Relations, eds. S. Worchel and W.G. Austin. Chicago: NelsonHall. Tolbert, Caroline J., and John A. Grummel. 2003. “Revisiting the Racial Threat Hypothesis: White Voter Support for California‟s Proposition 209.” State Politics and Policy Quarterly 3: 183-202. Tsukashima, Ronald, and Darrel Montero. 1976. “The Contact Hypothesis: Social and Economic Contact and Generational Changes in the Study of Black Anti-Semitism.” Social Forces 55: 149-165. Voss, D. Stephen. 2000. Familiarity Doesn't Breed Contempt: The Political Geography of Racial Polarization. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University Dept. of Government. Voss, D. Stephen, and Penny Miller. 2001. “Following the False Trail: The Hunt for White Backlash in Kentucky‟s 1996 Desegregation Vote.” State Politics and Policy Quarterly 1: 62-80. Welch, Susan, and Lee Sigelman. 2000. “Getting to Know You? Latino-Anglo Social Contact.” Social Science Quarterly 81: 67-83. Welch, Susan, Lee Sigelman, Timothy Bledsoe, and Michael Combs. 2001. Race & Place: Race Relations in an American City. New York: Cambridge University Press. Williams, Allen. 1964. “Reduction of Tension through Intergroup Contact.” Pacific Sociological Review 7: 81-88. 23 Table 1. Descriptive Summary Statistics of Policy and Social Context Variables Immigrants help/hurt economy? Anglos only Latinos only Legal immigration increase/decrease? Anglos only Latinos only Agree/disagree with border fence? Anglos only Latinos only % Latino population % native-born Latino population % foreign-born Latino population 24 Min Max Mean 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 5 5 5 5 5 5 0.58 0.42 0.69 2.81 2.89 3.77 3.11 2.75 3.40 Std. Dev. 0.49 0.50 0.46 1.21 1.44 1.14 1.44 1.44 1.36 2.54 0 1.30 94.28 65.28 29.50 25.07 16.40 8.65 21.83 17.03 7.09 Table 2. Latino Context and Anglo Attitudes toward Immigration Logit Analysis for “Positive Economic Impact”; Ordered Logit Analysis for “Increase Legal Immigration” and “Oppose Border Fence” Dependent Variable= Positive Economic Impact Increase Legal Immigration Oppose Border Fence Anglo Respondent -.735 (.494) -.015 (.365) .045 (.452) Latino Group Size .014** (.005) .013** (.004) .007 (.004) Anglo Respondent "X" Latino Group Size -.023* (.011) -.019* (.008) -.024* (.001) Native-born Latino Respondent -1.286** (.260) -.056 (.195) -.689** (.185) Anglo-Latino Segregation .000 (.018) .025± (.015) -.006 (.013) Education -.047 (.119) .203** (.074) .127 (.084) Income .020 (.042) -.042 (.045) -.011 (.033) Democrat .152 (.184) -.175 (.160) .067 (.199) Republican .095 (.225) -.302 (.296) -.630** (.200) Bush approval -.049 .064 .006 (.028) .022 (.024) Female .078 (.193) -.179 (.162) .208 (.143) Catholic .361 (.219) .116 (.160) .356* (.145) Cut 1 .197 (.821) -1.701 (.812) Cut 2 1.169 (.857) -.302 (.822) Cut 3 2.732 (.867) .111 (.826) Cut 4 4.195 (.873) 1.402 (.797) N 469 474 505 2 Wald χ 164.27 96.55 139.45 Prob > Wald χ2 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 PRE .17 .06 .10 Note: ±p<.1 *p<.05 **p<.01. Standard errors are in parentheses and are clustered by county. Constant coefficients not presented. 25 Table 3. The Conditional Effect of Latino Context on Attitudes toward Immigration Predicted Probability Calculations Probability of Agreement for: Positive Economic Impact Increase Legal Immigration Oppose Border Fence Anglo Respondents Residing in areas with few Latinos (Set to minimum value of 2% Latino) .45 .23 .48 Residing in areas with many Latinos (Set to maximum value of 94% Latino) .27 .05 .16 Residing in areas with few Latinos (Set to minimum value of 2% Latino) .64 .24 .49 Residing in areas with many Latinos (Set to maximum value of 94% Latino) .87 .51 .65 Residing in areas with few Latinos (Set to minimum value of 2% Latino) .33 .23 .33 Residing in areas with many Latinos (Set to maximum value of 94% Latino) .65 .50 .48 Foreign-Born Latino Respondents Native-Born Latino Respondents 26 Table 4. Foreign-born Context and Anglo Attitudes toward Immigration Logit Analysis for “Positive Economic Impact”; Ordered Logit Analysis for “Increase Legal Immigration” and “Oppose Border Fence” Dependent Variable= Positive Economic Impact Increase Legal Immigration Oppose Border Fence Anglo Respondent -.1.403* (.556) .111 -.255 (.486) Latino Foreign-born Group Size .030 (.024) .049* (.020) .021 (.013) Anglo Respondent "X" Latino Foreign-born Group Size -.005 (.028) -.055* (.023) -.027 (.024) Native-born Latino Respondent -1.300** (.250) -.055 (.197) -.689** (.181) Anglo- FB Latino Segregation -.006 (.024) .018 -.006 (.011) Education -.045 (.116) .199** (.076) .134 (.084) Income .012 (.041) -.046 (.046) -.012 (.035) Democrat .155 (.182) -.168 (.158) .065 (.206) Republican .101 (.229) -.245 (.288) -.619** (.198) Bush approval -.056 .062 .007 (.028) .022 (.025) Female .092 (.192) -.149 (.157) .197 (.143) Catholic .362 (.209) .101 (.157) .349* (.129) Cut 1 .317 (1.235) -1.681 (.812) Cut 2 1.288 (1.278) -.293 (.867) Cut 3 2.847 (1.296) .117 (.879) Cut 4 4.307 (1.311) 1.402 (.835) (.411) (.016) N 469 474 505 2 Wald χ 143.55 105.88 116.00 Prob > Wald χ2 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 PRE .11 .05 .07 Note: ±p<.1 *p<.05 **p<.01. Standard errors are in parentheses and are clustered by county. Constant coefficients not presented. 27 Table 5. Native-born Context and Anglo Attitudes toward Immigration Logit Analysis for “Positive Economic Impact”; Ordered Logit Analysis for “Increase Legal Immigration” and “Oppose Border Fence” Dependent Variable= Positive Economic Impact Increase Legal Immigration Oppose Border Fence Anglo Respondent -.839* (.397) -.270 (.330) -.187 (.456) Latino Native-born Group Size .019** (.006) .014** (.004) .009* (.006) Anglo Respondent "X" Latino Native-born Group Size -.038** (.013) -.021* (.009) -.030** (.013) Native-born Latino Respondent -1.296**(.262) -.075 (.204) -.698** (.184) Anglo- NB Latino Segregation -.005 (.021) .023 -.007 (.016) Education -.051 (.119) .191* (.074) .125 (.083) Income .018 (.042) -.040 (.045) -.014 (.031) Democrat .154 (.194) -.185 (.158) .071 (.201) Republican .090 (.244) -.321 (.303) -.631** (.200) Bush approval -.048 .065 .005 (.029) .019 (.024) Female .071 (.196) -.169 (.159) .206 (.141) Catholic .360 (.217) .117 (.160) .351** (.083) Cut 1 -.256 (.805) -1.876 (.863) Cut 2 .712 (.831) -.477 (.872) Cut 3 2.269 (.842) -.063 (.876) Cut 4 3.730 (.856) 1.228 (.865) (.016) N 469 474 505 2 Wald χ 165.60 83.30 131.02 Prob > Wald χ2 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 PRE .16 .07 .09 Note: ±p<.1 *p<.05 **p<.01. Standard errors are in parentheses and are clustered by county. Constant coefficients not presented. 28 -1 -.5 0 .5 Figure 1. The Marginal Effect of Ethnicity on Beliefs about the Economic Impact of Immigration. 0 20 40 60 Percent_Latino Dashed lines give 95% confidence interval. 29 80 100 Appendix A. Survey Question Wording Dependent variables Economic Impact: “Some people say undocumented or illegal immigrants help the economy by providing low-cost labor. Others say they hurt the economy by driving wages down. Which is closer to your views?” Immigration Levels: “Do you think the number of new legal immigrants allowed into the United States each year should be increased a lot, increased a little, neither increased nor decreased, decreased a little, or decreased a lot?” Border fence: “Some both inside and outside of government have advocated the construction of a border fence. What do you think? Do you strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree or strongly disagree that a fence should be built?” Control variables Education: “What is the highest level of education you have received?” Income: “What was your total household income last year before taxes? Just stop me when I read the correct category.” Partisanship: “Do you generally consider yourself a Democrat, a Republican, an independent, or something else?” Bush approval: “In general, do you approve or disapprove of the way in which the President has been handling his job?” Female gender: coded by surveyor. Catholic religious affiliation: “What is your religious preference? That is, are you Catholic, Protestant, some other religion? Or have no preference?” 30 1 This same effect has also been studied in other academic fields. For example, a number of sociological studies have examined the effect of racial context on intermarriage rates. See Blau, Blum, and Schwartz (1982) and Blau, Beeker, and Fitzpatrick (1984), e.g. 2 Unfortunately, the survey did not include questions asking for the respondent‟s citizenship status. Thus, it is likely that the Latinos represented in this survey include both Latino-Americans as well as some Latino immigrants. 3 The average inter-item covariance is .36. The scale reliability coefficient is .54. Based on this information, we choose to analyze each of the items separately. 4 The percentage of Latino non-citizens correlates with the percentage of foreign-born Latinos at .98. Our results are unchanged when accounting for citizenship instead of nativity. 5 Unfortunately, the Lewis Mumford Center offers data of Anglo-Latino segregation at the SMSA or the state level. While other works have examined the effect of Latino group size on Anglo attitudes using SMSA level data, we feel that the county level better captures a respondent‟s residential context. The effect of Latino group size is similar in terms of direction, significance, and substantive impact when replicating our findings using only SMSA level data. 6 While we argue that there is a theoretical reason to believe Anglos and Latinos react differently to ethnic context, we do not argue that the relationship between any individual-level characteristics, such as education, and immigration policy preferences differ according to ethnicity. In order to confirm this, we ran separate models for our Anglo and Latino samples. Our Chow test result did not allow us to reject the null hypothesis that the difference between the coefficients in the Anglo and Latino models is equal to zero. This provides some empirical support for our theoretical contention that distinct processes do not underlie the relationship 31 between any individual-level characteristics and immigration policy preferences for Anglos and Latinos. 7 While we argue that there is a theoretical reason to believe that the inclusion of an interaction term between ethnicity and Latino group size will improve the model we also test to see if the inclusion of the interaction improves the predictive capacity of the model. To do this we conducted a joint F-test of the interactive term to determine if they were jointly significant. The resulting F-statistic was significant at the .05 level for each of models we present, indicating that the interactive variables belong in the model. 8 Relying on a series of logit and ordered logit models can result in inefficient estimation, incorrect standard errors, and an increased probability of committing a Type I error due to the multilevel nature of our data. Our models contain ~500 respondents spread over 48 counties. We replicated our models using HLM 6. Our use of HGLM models presented an additional series of complications as only 21 of the 48 counties have sufficient data for computation. Moreover, an examination of the variance components in each of our models indicates that HLM is offering little leverage. In line with that one would expect given the series of non-significant variance components, our results do not change when relying on HGLM models (this is true even though the HGLM analysis eliminates over 50% of our level 2 units). 9 We considered the argument that native-born Latinos might hold conservative preferences when residing near a large foreign-born population. In order to test this hypothesis, we replicated our analysis in Table 4 on our Latino subsample. We included an interaction term between our “native-born” variable and the size of the Latino foreign-born population. We also created a measure of the percentage of all Latinos who are foreign-born. In neither case was the interaction term statistically significant. We take this as evidence that Latinos are generally more supportive 32 of liberal immigration policies in areas of high in-group size, although the base level of liberalism is lower for native-born Latinos. 33