3. Sampling

advertisement

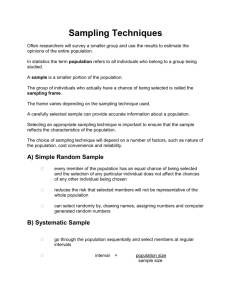

3. Sampling Key Terms: Biased sample Cluster sampling College freshman problem Diminishing returns Inferring (generalizing) Modified replication Mortality Pilot study Precision (of a sample) Purposive sampling Representativeness (term not used by Patten) Sample size Sample vs. population Samples of convenience (accidental samples) Sampling error Simple random sample Snowball sampling Strata Stratified random sampling Systematic sampling Table of random numbers Unbiased sample Volunteerism Key Principles: 3.1 Researchers are interested in understanding populations but most often conduct research using samples. 3.2 Researchers use samples to enable them to make inferences about a population, to generalize from a sample to a population. 3.3 No matter how good the sample, such inferences will always be imperfect because we can never be sure that the sample was perfectly representative of the population. 3.4 To the extent possible, we would like our samples to be unbiased, that is, representative of the population. 3.5 Simple random sampling will always create an unbiased sample. 3.6 Most samples in psychological research are likely to be biased. 3.7 Even when randomly drawn, samples are always subject to sampling error (which is different from the problem of bias). 3.8 Researchers can draw their sample systematically by choosing every nth individual from a population, but this method is open to bias. 3.9 The precision of a sample can be maximized using stratified random sampling. 3.10 Only those strata that might be relevant to the issue being studied and that are independent of each other are included in stratified random sampling. 3.11 Other sampling methods (cluster, purposive, snowball) have certain advantages but are never better than random sampling. 3.12 When demographics of a population and of a sample are known, researchers can use statistical methods to make unbiased samples more precise. 3.13 Researchers should openly acknowledge any known problems with the representativeness of their sample. 3.14 When possible, researchers should compare the demographics of their volunteer sample to the demographics of those who didn’t volunteer. 3.15 In experiments—or in any study that lasts over time—participants might drop out, and researchers should compare the demographics of those who stayed with those who dropped out. 3.16 Results of one single study are not definitive, and modified replications help to create more representative samples. 3.17 The bias of a sample is more of an issue in applied research, less of an issue in basic research. 3.18 Sample size is never as important as sample bias, and size alone cannot overcome bias. 3.19 Increased sample sizes increase the precision of an unbiased sample, but with diminishing returns. 3.20 There is no ideal sample size for a study. 3.21 Small samples are fine for pilot studies, for studies that involve expensive equipment and time-consuming procedures, for studying rare phenomena, and for studying very homogeneous populations. 3.22 Larger sample sizes are necessary when looking for small differences and for locating people with rare characteristics. 3.23 For a population of a finite size, it is possible to determine exactly the size of the sample needed to keep sampling error rate below 5%