WHO BEARS THE BURDEN OF U.S. NONTARIFF MEASURES?

advertisement

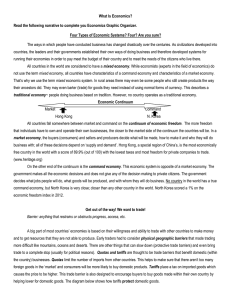

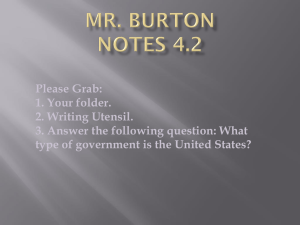

WHO BEARS THE BURDEN OF U.S. NONTARIFF MEASURES? DON P. CLARK and DONALD BRUCE* This article provides evidence on the incidence of U.S. nontariff measures (NTMs) by investigating the relationship between per capita income and various indicators of NTM use. Collectively, NTMs are found to bear heavily on products of export interest to the poorer countries. Antidumping duty actions and voluntary export restraint agreements primarily target newly industrializing and industrial nations in the middle third of the income scale. The overall protection pattern suggests poorer countries will find it difficult to escape NTMs by attaining higher levels of economic development. Results also provide insight into country and industry-level determinants of NTM use. (JEL F0, F1) I. INTRODUCTION NTMs are applied to the trade of countries that have widely different levels of economic wellbeing.1 This article provides evidence on the differential incidence of NTMs on products of export interest to developing countries by investigating the relationship between per capita income and various indicators of NTM use. Included here are import-licensing schemes, antidumping duty actions, tariff-rate quotas, price actions, import quotas, and voluntary export restraints (VERs). Results are used to determine whether advanced or poorer countries are the primary targets of trade restrictions used by the United States. Findings will also determine how the use of newer measures (e.g., VERs, antidumping duty actions) is influencing the overall pattern of protection faced by developing countries. Differences in incidence patterns displayed by voluntary Considerable attention has been devoted to the study of industrial nations’ trade policies and their impacts on developing countries. Tariffs used by industrial nations have been found to bear more heavily on products of export interest to developing countries than on imports from other industrial nations (see, for example, Balassa 1967; Clark 1981; Deardorff and Stern 1998; Laird and Yeats 1990). Successive rounds of multilateral trade negotiations have lowered tariffs facing developing countries in markets of industrial nations. As tariff barriers have fallen, industrial nations have used nontariff measures (NTMs) to provide relief from import competition. Some NTMs have been applied against technologically unsophisticated and unskilled labor intensive products of export interest to developing countries, and others have been aimed at exports from the newly industrializing countries. Although several studies have shown that NTMs tend to bear more heavily on products of export interest to developing countries than on imports from other industrial nations, they have not given adequate recognition to the disparate manner in which 1. Studies that compare simple average NTM trade coverage ratios for industrial nations and developing countries include Walter (1971), Laird and Yeats (1990), and Clark (1993). Clark (1998) investigates the relationship between NTM trade coverage and the level of economic development. None of these studies identified country or industry-level determinants of NTM use. Per capita GDP and the NTM trade coverage ratio display a significant correlation coefficient of –0.1028 in the present study. *The authors are grateful to the referees for providing many helpful comments and suggestions. Clark: Professor, Department of Economics, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN 37996-0550. Phone 1865-974-1706, Fax 1-865-974-4601, E-mail dclark3@ utk.edu Bruce: Associate Professor, Center for Business and Economic Research and Department of Economics, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN 37996-4170. Phone 1-865-974-6088, Fax 1-865-974-3100, E-mail dbruce@utk.edu ABBREVIATIONS GDP: Gross Domestic Product NTM: Nontariff Measure SIC: Standard Industrial Classification VER: Voluntary Export Restraint 274 Contemporary Economic Policy (ISSN 1074-3529) Vol. 24, No. 2, April 2006, 274–286 Advance Access publication October 5, 2005 doi:10.1093/cep/byj001 Ó Western Economic Association International 2005 No Claim to Original U.S. Government Works CLARK & BRUCE: THE BURDEN OF U.S. NONTARIFF MEASURES export restraints and import quotas will be highlighted. Several features of the present study represent improvements over earlier attempts to identify the intercountry pattern of NTM incidence. First, NTM trade coverage ratios are used to assess the incidence of NTMs imposed by the United States on imports from countries that span the entire range of per capita incomes. Previous studies compare simple average NTM trade coverage ratios for industrial nations and developing countries. Second, the present study of the relationship between NTM use and the level of economic development identifies both country- and industry-level determinants of NTM use. Earlier studies focus only on industry-level determinants. A third improvement pertains to the scope of country and industry coverage. The present study is based on 72 countries and includes more than 370 four-digit U.S. Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) industries. Other studies use far fewer observations and a much higher level of industry aggregation. Fourth, unlike previous studies, the authors provide estimates for all NTMs and for individual categories of trade control measures, such as antidumping duty actions, quantitative restrictions, import quotas, and voluntary export restraints. Finally, the data pertain to 1992 and account for newer trade control measures such as antidumping duties and VER agreements. Previous studies use data from the early 1980s. II. DETERMINANTS OF NONTARIFF MEASURES The purpose here is to empirically examine the incidence of U.S. NTMs on imports from countries that span the entire per capita income distribution. The authors focus on a regression approach that specifies NTM trade coverage as a function of per capita income. For such an approach to yield unbiased estimates, other important determinants of NTM coverage must be included in the model. The authors examine a broad array of country and industry-level determinants of NTM use. Variable definitions and measurement issues are discussed in the appendix. Country-Level Determinants NTMs are expected to bear more heavily on products of export interest to developing 275 countries than on imports from other industrial nations. According to the Heckscher-Ohlin theorem, each country will export the good that uses its abundant factor intensively and import the good that is intensive in its relatively scarce factor. The abundant factor gains from trade and the scarce factor loses. Unskilled labor, the true scarce U.S. productive factor, will have an incentive to secure protection from foreign competition. As a result, many technologically unsophisticated and unskilled labor-intensive products of export interest to developing countries have been targets of protectionist actions. The most restrictive barriers apply to certain agricultural products and textiles and apparel. Developing countries are not in a position to retaliate against discriminatory trade practices of developed countries and do not have bargaining power to win major concessions in multilateral trade negotiations. Some forms of protection are product and industry-specific. The export composition of countries tends to vary as higher levels of economic development are attained. Although the exact nature of the intercountry pattern of incidence might vary from one trade restriction to another, the authors expect overall NTM use will be negatively correlated with per capita incomes of U.S. trade partners. Other country-level determinants are not well established in the empirical literature. The authors use country characteristics that can be expected to influence the export potential of foreign countries under the assumption that import surges will be countered with trade restrictions. Gross domestic product (GDP) of trading partners measures production and reflects export capabilities of countries. For example, newly industrialized countries enjoyed rapid growth in the 1980s and became major targets of U.S. protectionist actions. NTM use is expected to be positively correlated with the GDP of trading partners. Geographical characteristics are expected to exert important influences over trade. These characteristics include size and proximity to other countries, and whether they share a border with the United States. Frankel and Romer (1999) found countries that encompass large areas tend to engage in more within-country trade and less external trade. This suggests NTM use and area will be negatively correlated. Leamer (1984) argues that area might also serve as a proxy for resource availability that would stimulate exports and protectionism 276 CONTEMPORARY ECONOMIC POLICY in the importer. Costs associated with overcoming distance lead us to expect that countries in close proximity to the United States will account for more imports than distant countries. These effects will be most pronounced for border countries. Proximity to trading partners reflects such factors as seasonal trade, border trade, regional economic integration, cultural and language differences, and general market familiarity. NTM use is expected to be negatively correlated with distance from the trading partner and higher for border countries. The authors do not hypothesize a sign for the coefficient on the area measure. It is widely recognized that countries will grow and industrialize faster by adopting outward-oriented trade strategies than by using import-substitution industrialization policies (see Clark et al. 1993; Dollar 1992). Economies that are open to trade use export-oriented strategies. Export surges will be countered with trade restrictions in the United States. NTM use is expected to be positively correlated with trade orientation of a trading partner. Major petroleum-exporting countries supply petroleum and related products. They have not traditionally specialized in the production and export of manufactured goods. These countries occupy all positions on the income scale. A dummy variable is used to identify major petroleum countries. NTM use is expected to be lower for major petroleum exporters. Industry-Level Determinants Considerable research effort has been devoted to identifying industry-level determinants of trade barrier use.2 Analyses have been conducted using a wide variety of protectionformation models.3 These studies have emphasized determinants of protection structure relating to pressure-group formation incentives, group voting strengths, equity considerations, international bargaining positions, comparative advantage, the economic theory 2. See Pincus (1975), Caves (1976), Helleiner (1977), Clark (1980, 1987), Ray (1981a, 1981b, 1987), Finger et al. (1982), Ray and Marvel (1984), Herander and Schwartz (1984), Feinberg and Hirsch (1989), Trefler (1993), Lee and Swagel (1997), Gawande (1998), Goldberg and Maggi (1999), and Gawande and Bandyopadhyay (2000). 3. See, for example, Olson (1965), Caves (1976), Brock and Magee (1978), Baldwin (1982), Marvel and Ray (1983), and Grossman and Helpman (1994). of regulation, strategic retaliation, endogenous protection, and historical protection patterns. Protection-formation models have a common goal. They seek to explain who will have an incentive to secure protection from import competition and who will bear the burdens. Protection is valuable to import sensitive industries. Benefits of trade restrictions are concentrated in politically powerful domestic industries, and the costs are dispersed throughout the entire economy. Winners and losers from protection are identified by focusing on measures of constituent political power which influence an industry’s ability to secure protection. Imports serve the same economic purpose as entry. When market structure characteristics enable firms to enjoy profits at home but do not deter foreign competition, these firms will have an incentive to restrict market entry by foreign rivals (see Stigler 1971; Trefler 1993). Their ability to accomplish this objective will depend on the levels of political influence they possess. Several market structure characteristics serve as domestic entry barriers. These include the degree of scale economies, degree of product differentiation, and the extent of market concentration. Industry size conveys political power. Comparative disadvantage activities will be candidates for protection, whereas industries insulated from import competition by high transportation charges will have less need for trade restrictions. Scale economies restrict entry by domestic firms. Industries that enjoy scale economies are quite susceptible to import growth (see Clark et al. 1990). Protection will be more valuable to industries that enjoy benefits associated with large-scale production. Scale economies also lead to industry size and more political power. NTM use is expected to be positively correlated with the degree of scale economies. The relationship between industry concentration and political power is rooted in Olson’s (1965) theory of collective goods. Seller concentration determines political power of an industry’s special interest groups by influencing their ability to mobilize members and by lowering incentives to free ride. When a few firms account for a large share of industry sales, they will find it easier to mobilize support for a common goal, such as securing trade restrictions. Gains from protection will be concentrated among members of a small group rather than being dispersed over many CLARK & BRUCE: THE BURDEN OF U.S. NONTARIFF MEASURES firms. NTM use is expected to be positively correlated with the degree of industry seller concentration. Product differentiation serves to restrict both domestic and foreign entry. Industries that produce differentiated products will require less protection to compete with foreign rivals than will industries that produce homogenous goods. Product differentiation is proxied by the advertising-sales ratio.4 Advertising is intended to differentiate products, exploit quality differences, shift the demand curve rightward, and/or reduce the price elasticity of demand for a product. Increased product differentiation is expected to make it difficult for foreign producers to penetrate the U.S. market. As such, NTM use should be negatively correlated with the degree of advertising intensity. Industry size or importance translates into political power. Large industries will be more successful in securing protection than smaller ones. Industry size is measured by an industry’s share in total manufacturing employment. NTM use is expected to be positively correlated with industry size. Downstream consumers will influence an industry’s ability to secure trade restrictions. The sales dispersion index reflects the diversity of industry consumers. Lower values of the index are associated with industries that serve a wide range of industrial consumers who will exert political opposition to the demand for trade restrictions. When industries sell to a narrow range of downstream activities, political opposition from industrial consumers will go unnoticed or be deemed unimportant. NTM use should be positively correlated with the sectoral dispersion index. Comparative disadvantage industries will have an incentive to restrict import competition. Two variables are used to measure the cost disadvantage of an industry. Unskilled labor, the true scarce U.S. factor, has an incentive to secure protection from foreign competition. The average wage serves as a measure of unskilled labor intensity. Following Finger et al. (1982), the authors assume the U.S. comparative disadvantage is also pronounced in physical capital–intensive industries. Physical 4. Clark et al. (1990) found that product differentiation, measured by the advertising-sales ratio, is an effective deterrent to import growth. 277 capital intensity is measured by the capitalto-labor ratio. NTM use is expected to be negatively correlated with the average wage and positively correlated with the measure of capital intensity. A natural trade barrier is also expected to affect an industry’s need for trade restrictions. International transportation charges influence tradability of an industry’s products. Bulky products of relatively low unit values will tend to incur high ad valorem international shipping charges that tend to reduce the volume of trade. NTM use should be negatively correlated with ad valorem international transport charges. III. EMPIRICAL STRATEGY AND RESULTS Given the fact that the present measures of NTM coverage are restricted to the interval between 0% and 100% (inclusive), the multivariate econometric strategy must be able to account for clustering at the endpoints. All of the measures of NTM coverage have observed minima at 0 and maxima at 100 (summary statistics in the appendix). Consequently, the authors use two-limit tobits for multivariate analysis that pertain to NTM coverage. Because the focus is on the incidence of nontariff trade barriers across the per capita income distribution, it is useful to begin with an in-depth investigation of the importance of using an appropriate set of control variables. Table 1 presents the first set of tobit results, using the measure of all NTMs. These results illustrate the importance of including both industry and country characteristics in a model explaining NTM coverage. Column (1) presents a pared-down specification that includes only GDP and a quadratic of per capita GDP, in addition to a constant. In the absence of both industry and country effects, per capita GDP exerts an increasingly negative influence on the NTM coverage rate. However, including the country effects, as shown in column (2), changes the curvature of the effect of per capita GDP from increasingly negative to decreasingly negative (i.e., U-shaped). Interestingly, including industry variables in the absence of country effects, as in column (3), reverts to the increasingly negative influence. The baseline specification, presented in column (4), suggests a more 278 CONTEMPORARY ECONOMIC POLICY TABLE 1 Tobit Analysis: All Nontariff Measures Variable GDP ($b) Per capita GDP ($th) Per Capita GDP Squared ($m) (1) 0.041 (0.004) 1.997 (0.859) 0.070 (0.031) (2) *** ** ** ln(Area) ln(Distance) Borders U.S. Trade orientation Major petroleum exporter 0.048 (0.004) 6.082 (0.935) 0.042 (0.032) 5.690 (1.212) 22.381 (3.294) 164.684 (19.046) 15.344 (5.632) 32.477 (11.054) (3) *** *** *** *** *** Advertising-sales ratio Employment share Sales dispersion index Average wage Capital-labor ratio Transport Charge SE N *** 346.666 (28.812) 169.874 (4.724) 15,167 *** *** Seller concentration ratio 189.207 (7.078) 172.024 (4.789) 15,167 *** *** Scale economies Constant 0.041 (0.004) 1.059 (0.834) 0.087 (0.030) (4) *** 114.844 (31.814) 0.418 (0.146) 10.589 (132.633) 5060.884 (682.740) 14.124 (9.417) 0.007 (0.000) 0.481 (0.031) 165.228 (26.919) 21.733 (11.751) 162.421 (4.499) 15,167 *** *** *** *** *** *** * 0.047 (0.004) 4.668 (0.902) 0.013 (0.031) 3.891 (1.185) 22.083 (3.197) 149.070 (18.224) 16.979 (5.514) 31.298 (10.824) 117.007 (31.446) 0.399 (0.145) 1.931 (131.751) 5190.687 (678.277) 15.913 (9.355) 0.007 (0.000) 0.478 (0.031) 151.671 (26.832) 191.310 (28.922) 160.462 (4.440) 15,167 *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** * *** *** *** *** Note: Entries are tobit coefficients with SEs in parentheses. Asterisks denote statistical significance at the 1% (***), 5% (**), and 10% (*) levels. U-shaped relationship between per capita GDP on NTM coverage.5 Figure 1 is based on results in column (4) of Table 1. It illustrates the relationship between per capita GDP and NTM coverage. This figure shows the average predicted value of NTM coverage for each level of per capita GDP in the data set. The authors have superimposed a cubic trend line to provide a more detailed 5. Joint significance tests reveal the coefficients representing the quadratic effect of per capita GDP are highly statistically significant in all specifications. Experimentation with alternative functional forms (i.e., higher-order polynomials), yielded qualitatively identical results. analysis of this relationship. NTM coverage is above 8% for industries in the poorest countries. Trade coverage falls gradually through the first third of the distribution, falls less gradually for the middle portion of the distribution, and then falls more rapidly for countries with the very highest per capita GDP levels. This pattern of NTM use cannot be determined from a simple comparison of average NTM trade coverage ratios pertaining to industrial nations and developing countries. Collectively, NTMs are found to bear heavily on products of export interest to the poorer countries. This finding is not necessarily an CLARK & BRUCE: THE BURDEN OF U.S. NONTARIFF MEASURES 279 FIGURE 1 All Nontariff Measures 16 14 Coverage Rate (%) 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 0 5000 10000 15000 20000 25000 30000 35000 Per Capita GDP indication of deliberate action on the part of the United States to harm these countries. The United States’ comparative disadvantage is most pronounced in unskilled labor–intensive and technologically unsophisticated manufactured goods and agricultural products that are exported by poorer countries. Import quotas, tariff-rate quotas, price actions, and import-licensing schemes restrict trade in agricultural and manufactured products of export interest to these countries. The finding that NTM coverage falls less gradually over the middle portion of the distribution may be due to the offsetting effects of antidumping duty actions and VERs that are primarily targeted at the higher-income newly industrializing countries and industrial nations. Fortunately, the general patterns of both sign and significance for the remaining variables, with the exception of the advertisingsales ratio, seem to be unaffected across the various specifications. Looking first at the country characteristics in column (4) of Table 1, one can find that NTM coverage increases with GDP of a trading partner. Exports from countries that encompass smaller geographic areas tend to face higher levels of NTM coverage in the U.S. market. This finding supports the contention of Frankel and Romer (1999) that geographically large countries tend to engage in more within-country trade and less external trade. It does not support Leamer’s (1984) view that area might serve as a proxy for resource availability that would stimulate exports. The finding pertaining to the distance variable counters the authors’ expectations. NTM coverage is found to increase as the distance between the United States and a trading partner increases. The U.S. border countries of Canada and Mexico have much higher levels of NTM coverage. Outward-oriented trade strategy, as reflected in the trade orientation measure, exerts a positive influence on NTM coverage, whereas major petroleum exporters face lower NTM coverage in the U.S. market. Coefficients on industry-level variables, with one exception, are statistically significant and have the expected signs. Two domestic entry barriers exert significant influences on the pattern of NTM use. NTM coverage is higher for industries that enjoy both scale economies and high seller concentration.6 Protection is 6. Trefler (1993) and Gawande (1998) found significant negative relationships between a measure of NTM use and scale economies. Significant negative relationships between NTM use and seller concentration are reported in Ray (1981a, 1981b) and Marvel and Ray (1983). Trefler (1993) found a significant positive relationship between NTM use and seller concentration. 280 CONTEMPORARY ECONOMIC POLICY more valuable to industries that exhibit these characteristics. Scale economies and seller concentration also convey political power. Seller concentration preserves gains from protection for a smaller number of domestic firms. Advertising intensity is not found to exert a significant effect on NTM coverage. NTM use is also higher for large, politically important industries, as measured by the industry’s share in total manufacturing employment. The significant positive coefficient on the sectoral dispersion index shows industries serving a wide range of downstream industrial consumers will face more political opposition to their demands for protection. NTM use is higher for U.S. industries that have a pronounced comparative disadvantage, as reflected in lower average wage levels or higher capital intensity.7 Ad valorem international transportation charges, a natural trade barrier, exert a negative impact on NTM trade coverage ratios. Although the results in Table 1 provide key insights into the general incidence of NTMs, our data permit a similar assessment for various categories of NTMs.8 Included here are antidumping duty actions and quantitative restrictions. The latter is largely comprised of import quotas and VERs. Table 2 presents full specifications for these NTM categories. The authors begin the discussion of Table 2 by focusing on the per capita GDP results, which vary dramatically across the four categories. Antidumping duty actions and VERs display similar incidence patterns. Per capita GDP exerts an inverted U-shaped effect on NTM coverage in each of these cases. In other words, NTM coverage increases with per capita GDP up to some maximum point, and then falls as per capita GDP increases beyond this maximum. Conversely, quantitative restrictions and import quotas display more of a U-shaped relationship between per capita income and NTM coverage. Figures 2 through 5 illustrate relationships between per capita GDP and NTM coverage for antidumping duties, quantitative restric7. Lee and Swagel (1997) established a significant positive relationship between NTM use and the average wage. Ray (1981a, 1981b) found a significant positive relationship between NTM use and capital intensity. 8. The number of country-industry observations for automatic and nonautomatic licenses, tariff-rate quotas, and price actions is too small to permit an assessment of their separate incidences. tions, import quotas, and VERs. Each figure shows the average predicted values of NTM trade coverage for each level of per capita GDP. The authors have superimposed a cubic trend line to provide a more detailed picture of the incidence of these measures across the entire per capita income scale. Over the years, industrial nations have increased their reliance on bilateral or discriminatory measures, such as antidumping duty actions and VERs to counter import surges from specific supply sources that are not covered by import quotas, licensing schemes, price actions, or tariff-rate quotas. Because antidumping duty actions can be focused on a specific product from a particular supply source, they are often referred to as made-to-measure protection. The mere threat of antidumping duty actions and the potential harassment involved in the investigative procedures can lead foreign exporters to raise prices and restrict shipments (see Herander and Schwartz 1984). Antidumping duty actions and VERs display an inverted U-shaped relationship with per capita GDP in Figures 2 and 5. NTM coverage of these measures appears to rise with per capita income of trading partners, reaching a peak at relatively high per capita income levels and falling with per capita GDP thereafter. These measures appear to be primarily targeted at countries in the middle and upper portions of the income scale. Japan, Canada, Taiwan, and Thailand have the most trade subject to U.S. antidumping duties. VERs cover trade in certain motor vehicles, machine tools, various electronics products, primary and fabricated metal products, and some footwear. The United States negotiated VER agreements with 27 countries. Japan and Korea were primary targets. Comparing Figure 1 with Figure 4 provides an indication of how antidumping duties and VERs influence the overall NTM incidence pattern. Trade coverage for all NTMs falls less gradually than trade coverage for import quotas throughout the middle and high-income parts of the per capita income scale due to the offsetting effects of antidumping duties and VERs that primarily target newly industrializing countries and industrial nations. Figures 3 and 4 show that quantitative restrictions and one major component, import quotas, are heavily biased against products of export interest to the poorer countries. Trade coverage in each of these cases falls more CLARK & BRUCE: THE BURDEN OF U.S. NONTARIFF MEASURES 281 TABLE 2 Tobit Analysis: Individual Nontariff Measure Categories Variable GDP ($b) Per capita GDP ($th) Per capita GDP squared ($m) ln(Area) ln(Distance) Borders U.S. Trade orientation Major petroleum exporter Scale economies Seller concentration ratio Advertising-sales ratio Employment share Sales dispersion index Average wage Capital-labor ratio Transport charge Constant SE N Antidumping Duty Actions (AD) 0.049 (0.006) 2.335 (1.189) 0.171 (0.047) 2.508 (1.492) 22.815 (4.343) 107.951 (20.534) 6.570 (6.573) 55.895 (21.932) 270.112 (118.669) 0.221 (0.189) 761.106 (209.217) 4010.740 (632.422) 71.282 (12.848) 0.0003 (0.000) 0.061 (0.035) 258.309 (59.465) 399.012 (43.753) 110.475 (5.849) 15,167 *** ** *** * *** *** ** ** *** *** *** * *** *** Quantitative Restrictions (QR) 0.045 (0.007) 7.306 (1.350) 0.0263 (0.048) 5.056 (1.664) 24.528 (4.547) 166.547 (26.875) 31.621 (7.923) 40.059 (14.831) 273.897 (41.314) 0.355 (0.220) 128.818 (187.172) 4303.239 (1090.914) 33.617 (13.324) 0.0120 (0.001) 0.458 (0.054) 158.127 (38.310) 131.908 (41.105) 198.767 (7.067) 15,167 *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** ** *** *** *** *** Import Quotas (IQ) 0.036 (0.008) 10.508 (1.498) 0.1010 (0.053) 7.573 (1.771) 33.647 (4.858) 233.155 (28.801) 37.852 (8.495) 43.809 (15.612) 331.997 (42.774) 1.131 (0.244) 310.692 (196.303) 2155.153 (1331.611) 10.900 (14.659) 0.0169 (0.001) 0.578 (0.062) 198.464 (42.525) 73.880 (43.571) 194.030 (7.389) 15,167 *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** * Voluntary Export Restraints (VER) 0.051 (0.013) 16.267 (3.753) 0.504 (0.128) 20.781 (5.901) 40.073 (13.810) 244.210 (83.902) 0.560 (19.825) 1.831 (42.312) 989.604 (662.344) 4.679 (0.864) 595.527 (606.232) 3096.337 (2024.164) 132.382 (34.286) 0.009 (0.002) 0.166 (0.109) 53.364 (54.857) 592.415 (127.398) 233.142 (24.040) 15,167 *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** Note: Entries are tobit coefficients with SEs in parentheses. Asterisks denote statistical significance at the 1% (***), 5% (**), and 10% (*) levels. rapidly throughout the per capita income scale than is the case for all NTMs. Agricultural, textile and apparel products face import quotas in the U.S. market. Import quotas apply to milk, cheese, peanuts, cotton, some sugarcontaining products, and other agricultural products. Textile and apparel quotas apply to imports from many developing countries. Trade subject to import quotas is highly concentrated among the lower-income countries. The primary targets of import quotas include China, India, Thailand, Taiwan, Korea, and Hong Kong. Patterns of NTM incidence for import quotas and quantitative restrictions (including import quotas, nonautomatic import licensing schemes, and VERs) are quite similar. This finding suggests that import quotas play a major role in shaping the overall pattern of NTM use across the entire per capita income scale. Comparing Figure 3 with Figure 4 shows how VERs influence the country incidence pattern associated with all quantitative restrictions. Trade coverage for quantitative restrictions falls more gradually than trade coverage for import quotas throughout the middle and 282 CONTEMPORARY ECONOMIC POLICY FIGURE 2 Antidumping Duty Actions 6 Coverage Rate (%) 5 4 3 2 1 0 0 5000 10000 15000 20000 25000 30000 35000 Per Capita GDP upper-middle portions of the per capita income scale. The middle and upper-middle income bias associated with VERs is illustrated in Figure 5. Turning to other covariates in Table 2, it is interesting to note that only two of the control variables are found to have consistent effects on NTM coverage across the various catego- ries. Specifically, country-level GDP and the industry-level employment share are both associated with higher degrees of NTM coverage regardless of the NTM category. All other factors have different effects by NTM type, revealing the importance of conducting analysis of determinants of NTM coverage at a disaggregated level. FIGURE 3 Quantitative Restrictions 16 14 Coverage Rate (%) 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 0 5000 10000 15000 20000 Per Capita GDP 25000 30000 35000 CLARK & BRUCE: THE BURDEN OF U.S. NONTARIFF MEASURES 283 FIGURE 4 Import Quotas 18 16 Coverage Rate (%) 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 0 5000 10000 15000 20000 25000 30000 35000 Per Capita GDP IV. CONCLUSIONS This study examines the relationship between per capita income of U.S. trade partners and various indicators of NTM use. Collectively, NTMs are found to bear heavily on products of export interest to the poorest countries. This finding is not necessarily an indication of deliberate action on the part of the United States to harm these countries. The U.S. comparative disadvantage is most FIGURE 5 Voluntary Export Restraints 2.5 Coverage Rate (%) 2 1.5 1 0.5 0 0 5000 10000 15000 20000 Per Capita GDP 25000 30000 35000 284 CONTEMPORARY ECONOMIC POLICY pronounced in unskilled labor–intensive and technologically unsophisticated manufactured goods and agricultural products exported by these countries. Trade coverage for all NTMs falls gradually throughout the first third of the per capita income distribution, falls less gradually for the middle of the distribution, and then falls more rapidly for the countries with the highest per capita income. Quantitative restrictions and import quotas display an incidence pattern similar to that associated with all NTMs. The finding that NTM coverage falls less gradually over the middle portion of the per capita income distribution is due to the offsetting effects of antidumping duty actions and VERs that primarily target newly industrializing countries and industrial nations in the middle and upper-middle portions of the per capita income scale. This incidence pattern suggests poorest countries will not be able to escape NTMs by attaining higher levels of economic development. Results also provide insight into country and industry-level determinants of the overall incidencepatternofNTMs.Exportsfromcountries with higher GDPs, outward-oriented countries, and those sharing a border with the United States face higher levels of NTM coverage. Distance between the United States and a trading partner also increases NTM use. Geographical area and specialization in petroleum exports exert negative effects on NTM coverage. Country characteristics have more diverse effects on protection patterns displayed by the various NTM categories than do industry-level characteristics. Industry-level results are consistent with predictions of political economy models. Scale economies, seller concentration, manufacturing employment share, and capital intensity exert positive impacts on the overall pattern of NTM incidence. The average wage and ad valorem international transport charge lower NTM coverage. Industry characteristics have similar effects on protection patterns exhibited by tariffs and all NTMs. APPENDIX: DATA DEFINITIONS AND SOURCES Nontariff Measures The incidence of NTMs on imports is assessed by using the trade coverage ratio, which measures the share of imports (by value) subject to a given NTM. The value of imports covered by a given NTM was determined by matching imports at the tariff-line level from each supply source with information on product and country-specific NTMs applied in 1992, recorded in the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) database on Trade Control Measures. Trade coverage figures were aggregated to the four-digit SIC level, and trade coverage ratios were calculated for all NTMs and various NTM categories. Shortcomings inherent in the use of trade coverage ratios are discussed in Clark and Zarrilli (1992). The ‘‘all NTMs’’ category includes all NTMs applied at the border by the United States for which information is included in UNCTAD’s database. Included here are paratariff measures such as tariff-rate quotas, import licensing schemes, antidumping duty actions, price actions, import quotas, and VERs. Quantitative restrictions restrict the quantity of imports of a particular good from all sources or from a single supply source. Nonautomatic licenses, import quotas, and VERs are included in this category. Antidumping duty actions include investigations to determine whether imports are sold at less-than-fair value, imposing duties to offset dumping, and measures taken by importers to counter effects of dumping. Trade coverage ratios are also calculated for individual NTMs such as antidumping duty actions, import quotas and VERs. Country-Level Determinants Figures on GDP and per capita GDP pertain to 1992 and are taken from United Nations (1997). Area in thousands of square miles is from Frankel and Romer (1999). Distance in kilometers is from Fitzpatric and Modlin (1986). The border country dummy variable equals 1 for Canada and Mexico and 0 otherwise. Following Stone and Lee (1995) and Balassa and Bauwens (1987), trade orientation is proxied by the residuals from a regression of per capita merchandise trade (exports plus imports) on per capita income and population. Data are from United Nations (1997). Major petroleum exporters are identified in United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (2001). Industry-Level Determinants The 1987 four-firm seller concentration ratio is reported in U.S. Bureau of the Census (1992). Minimum efficient scale, the scale economy measure, is defined as average sales per firm for firms in the midpoint class size (defined by product shipments) as a percent of shipment values. The capital-to-labor intensity ratio is expressed in millions of U.S. dollars of capital per worker. The average wage is total employee compensation per worker. The employment share is the share of total manufacturing employment accounted for by an industry. These figures pertain to 1992 and are from the U.S. Bureau of the Census (1995). Ad valorem international transport charges are from the U.S. Bureau of the Census (1993). The sectoral dispersion index DSPHi ¼ Rnk¼1 s2i;k ; where si,k is the share of industry i’s sales to two-digit consuming industry k. See Lustgarten (1975). This variable and the advertising-sales ratio pertain to 1987 and are calculated from a U.S. Department of Commerce (1994) publication. CLARK & BRUCE: THE BURDEN OF U.S. NONTARIFF MEASURES 285 TABLE A1 Summary Statistics Variable All nontariff barriers Antidumping duty actions Quantitative restrictions Import quotas Voluntary export restraints GDP ($m) Per capita GDP ($) ln(Area) ln(Distance) Borders U.S. Trade orientation Major petroleum exporter Scale economies Seller concentration ratio Advertising-sales ratio Employment share Sales dispersion index Average wage Capital-labor ratio Transport charge Mean SD 6.356 0.838 5.046 4.529 0.495 363,387 11,935 4.367 8.637 0.049 0.033 0.054 0.026 37.641 0.019 0.002 0.462 32,940 68.685 0.086 22.634 7.776 20.638 19.624 6.610 666,740 10,588 2.398 1.214 0.215 0.522 0.226 0.073 19.436 0.018 0.003 0.265 9,947 89.468 0.121 REFERENCES Balassa, B. ‘‘The Impact of the Industrial Countries Tariff Structure on their Imports of Manufactures from Less Developed Areas.’’ Economica, 34, 1967, 372–83. Balassa, B., and L. Bauwens. ‘‘Intra-Industry Specialisation in a Multi-Country and Multi-Industry Framework.’’ Economic Journal, 97(388), 1987, 923–39. Baldwin, R. E., ‘‘The Political Economy of Protectionism,’’ in Import Competition and Response, edited by Jagdish Bhagwati. Chicago: University Press of Chicago, 1982, 263–90. Brock, W. P., and S. P. Magee. ‘‘The Economics of Special Interest Politics: The Case of Tariffs.’’ American Economic Review, 68(2), 1978, 246–50. Caves, R. E. ‘‘Economic Models of Political Choice: Canada’s Tariff Structure.’’ Canadian Journal of Economics, 9(2), 1976, 278–300. Clark, D. P. ‘‘The Protection of Unskilled Labor in the United States Manufacturing Industries: Further Evidence.’’ Journal of Political Economy, 88(6), 1980, 1249–54. ———. ‘‘Protection by International Transport Charges: Analysis by Stage of Fabrication.’’ Journal of Development Economics, 8(3), 1981, 339–45. ———. ‘‘Regulation of International Trade in the United States: The Tokyo Round.’’ Journal of Business, 60(2), 1987, 297–306. ———. ‘‘Non-Tariff Measures and Developing Country Exports.’’ Journal of Developing Areas, 27(2), 1993, 163–72. ———. ‘‘Are Poorer Developing Countries the Targets of U.S. Protectionist Actions?’’ Economic Development and Cultural Change, 47(1), 1998, 193–207. Minimum Maximum 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 1,624 215 2.303 2.303 0.000 1.506 0.000 0.000 2.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 14,092 3.912 0.000 100.000 100.000 100.000 100.000 100.000 3,725,205 34,564 9.060 9.677 1.000 1.325 1.000 1.000 93.000 0.150 0.024 1.172 65,036 762.104 4.989 Clark, D. P., D. L. Kaserman, and D. Anantanasuwong. ‘‘A Diffusion Model of Industrial Sector Growth in Developing Countries.’’ World Development, 21(3), 1993, 421–28. Clark, D. P., D. L. Kaserman, and J. W. Mayo. ‘‘Barriers to Trade and the Import Vulnerability of U.S. Manufacturing Industries.’’ Journal of Industrial Economics, 38(4), 1990, 433–47. Clark, D. P., and S. Zarrilli. ‘‘Non-Tariff Measures and Industrial Nation Imports of GSP-Covered Products.’’ Southern Economic Journal, 59(2), 1992, 284–93. Deardorff, A. V., and R. M. Stern. Measurement of Nontariff Barriers. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1998. Dollar, D. ‘‘Outward-Oriented Developing Countries Really Do Grow More Rapidly: Evidence from 95 LDCs, 1976–1986.’’ Economic Development and Cultural Change, 40(3), 1992, 523–44. Feinberg, R. M., and B. T. Hirsch. ‘‘ Industry Rent Seeking and the Filing of ÔUnfair TradeÕ Complaints.’’ International Journal of Industrial Organization, 7(3), 1989, 325–40. Finger, J. M., H. K. Hall, and D. R. Nelson. ‘‘The Political Economy of Administered Protection.’’ American Economic Review, 72(3), 1982, 452–66. Fitzpatric, G. L., and M. J. Modlin. Direct-Line Distances: International Edition. Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 1986. Frankel, J. A., and D. Romer. ‘‘Does Trade Cause Growth?’’ American Economic Review, 89(3), 1999, 379–99. Gawande, K. ‘‘Comparing Theories of Endogenous Protection: Bayesian Comparison of Tobit Models 286 CONTEMPORARY ECONOMIC POLICY Using Gibbs Sampling Output.’’ Review of Economics and Statistics, 80(1), 1998, 128–40. Gawande, K. and U. Banyopadhyay. ‘‘Is Protection for Sale? Evidence on the Grossman-Helpman Theory of Endogenous Protection.’’ Review of Economics and Statistics, 82(1), 2000, 139–52. Goldberg, P. K., and G. Maggi. ‘‘Protection for Sale: An Empirical Investigation.’’ American Economic Review, 89(5), 1999, 1135–55. Grossman, G. M., and E. Helpman. ‘‘Protection for Sale.’’ American Economic Review, 84(4), 1994, 833–50. Helleiner, G. K. ‘‘The Political Economy of Canada’s Tariff Structure: An Alternative Model.’’ Canadian Journal of Economics, 10(2), 1977, 318–26. Herander, M. G., and B. Schwartz. ‘‘An Empirical Test of the Impact of the Threat of U.S. Trade Policy: The Case of Antidumping Duties.’’ Southern Economic Journal, 51(1), 1984, 59–79. Laird, S., and A. Yeats. Quantitative Methods for Trade Barrier Analysis. New York: New York University Press, 1990. Leamer, E. E. Sources of International Comparative Advantage: Theory and Evidence. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1984. Lee, J. W., and P. Swagel. ‘‘Trade Barriers and Trade Flows across Countries and Industries.’’ Review of Economics and Statistics, 79(3), 1997, 372–82. Lustgarten, S. H. ‘‘The Impact of Buyer Concentration in Manufacturing Industries.’’ Review of Economics and Statistics, 57(2), 1975, 125–32. Marvel, H. P., and E. Ray. ‘‘The Kennedy Round: Evidence on the Regulation of International Trade in the United States.’’ American Economic Review, 73(1), 1983, 190–97. Olson, M. The Logic of Collective Action. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1965. Pincus, J. J. ‘‘Pressure Groups and the Pattern of Tariffs.’’ Journal of Political Economy, 83(4), 1975, 757–78. Ray, E. J. ‘‘The Determinants of Tariff and Nontariff Trade Restrictions in the United States.’’ Journal of Political Economy, 89(1), 1981a, 105–21. ———. ‘‘Tariff and Nontariff Barriers to Trade in the United States and Abroad.’’ Review of Economics and Statistics, 63(2), 1981b, 161–68. ———. ‘‘Intraindustry Trade: Sources and Effects on Protection.’’ Journal of Political Economy, 95(6), 1987, 1278–91. Ray, E. J., and H. P. Marvel. ‘‘The Pattern of Protection in the Industrialized World.’’ Review of Economics and Statistics, 64(3), 1984, 452–58. Stigler, G. ‘‘The Theory of Economic Regulation.’’ Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science, 2(1), 1971, 3–21. Stone, J. A., and H. H. Lee. ‘‘Determinants of IntraIndustry Trade: A Longitudinal, Cross-Country Analysis.’’ Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 131(1), 1995, 67–85. Trefler, D. ‘‘Trade Liberalization and the Theory of Endogenous Protection: An Econometric Study of U.S. Import Policy.’’ Journal of Political Economy, 101(1), 1993, 138–60. United Nations. Statistical Yearbook. New York: United Nations, 1997. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. 2001 Handbook of Statistics. New York: United Nations, 2001. U.S. Bureau of the Census. 1987 Census of Manufactures, Subject Series: Concentration Ratios in Manufacturing. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1992. ———. U.S. Exports and Imports of Merchandise on CD-ROM. Machine-readable data file, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau, 1993. ———. 1992 Census of Manufactures: Industry Series. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1995. U.S. Department of Commerce. Benchmark Input-Output Accounts for the U.S. Economy, 1987. Machinereadable data file, Washington, D.C.: Bureau of Economic Analysis, 1994. Walter, Ingo. ‘‘Nontariff Barriers and the Export Performance of Developing Economies.’’ American Economic Review, 61, 1971, 195–205.