CHAPTER 22 INTERNATIONAL FINANCIAL MARKETS AND INSTRUMENTS: An Introduction

advertisement

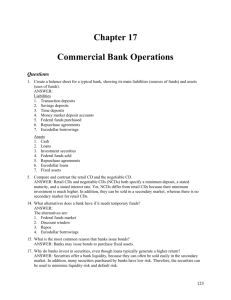

CHAPTER 22 INTERNATIONAL FINANCIAL MARKETS AND INSTRUMENTS: An Introduction I. Outline Introduction International Bank Deposits and Lending The International Bond Market International Stock Markets Financial Linkages and Eurocurrency Derivatives - Basic International Financial Linkages: A Review - International Financial Linkages and the Eurodollar Market - Hedging Eurodollar Interest Rate Risk -- Maturity Mismatching -- Future Rate Agreements -- Eurodollar Interest Rate Swaps -- Eurodollar Cross-Currency Interest Rate Swaps -- Eurodollar Interest Rate Futures -- Eurodollar Interest Rate Options -- Options on Swaps -- Equity Financial Derivatives The Current Eurodollar Derivatives Market Summary II. Special Chapter Features Case Study 1: Interest Rates across Countries Case Study 2: Stock Market Performance in Developing Countries Case Study 3: U.S. Domestic and Eurodollar Deposit and Lending Rates, 1989-1996 Box 1: How to Read Eurodollar Interest Rate Futures Market Quotations Box 2: How to Read Eurodollar Interest Options Quotations V. Answers to End-of-Chapter Questions and Problems 1. The growth in the Eurodollar markets was the result of a number of factors. For example, on the supply side, the oil shock in the 1970s and the accompanying build up of petro-dollars abroad was a key factor, as well as the sustained balance-of-payments deficits of the United States in the 1960s. In addition, European banks were able to offer relatively higher interest rates for Eurodollar deposits because they did not face interest rate ceilings such as that produced by Regulation Q in the United States, and they were willing to offer a higher rate because Eurodollar deposits were not subject to any legal reserve requirement and thus earned higher returns than other deposits. On the demand side, the tightening of the money supply in the United States in the 1960s made borrowing dollars in the United States more difficult for all, but especially for foreigners because of the foreign lending guidelines proposed by the Federal Reserve and the imposition of the interest equalization tax on loans made to foreigners. In addition, lending rates on Eurodollars were less than lending rates in the United States. Consequently foreign demand for Eurodollars increased. Finally, U.S. banks themselves contributed to the growth in demand for Eurodollars as they attempted to obtain dollar funds from their overseas branches during the tight money period when borrowing rates on Eurodollars were actually lower than borrowing rates at home. 2. Since the interest rate in the United States is less than that in England, the pound should be at discount (the U.S. dollar at premium) such that in financial equilibrium, the difference in the two rates is exactly offset by the difference between the spot and the forward and/or expected exchange rate, leaving the investor indifferent between the two markets. 3. One would expect the Eurodollar deposit rate to be above 6½ percent and the lending rate to be below 8½ percent. Because the Eurodollar deposits are not subject to the reserve requirements and other possible bank regulatory controls, including state and local taxes faced by domestic banks, Eurodollar deposits potentially earn more and therefore Eurobanks are willing to pay higher deposit rates and charge lower loan rates compared to similar loans in the United States. If local taxes on international financial activity were reduced, the respective deposit and lending rates would be expected to move more closely together. 4. Since the Eurodollar accounts are not subject to a reserve requirement or the 10 basis points deposit insurance costs, they should be willing to pay a deposit rate which is larger than 6½ percent by the equivalent costs of these two items. That is, they should be willing to pay a rate equal to (.065 + .001)/(1- .02) = .0673, or 6.73 percent. (See footnote 18 in the chapter.) 5. Bonds are initially issued for a specific face value, with a specific maturity date and a specific annual interest rate. The bond thus earns an amount each year equal to the stated interest rate times the face value (the coupon payment). With an increase in interest rates, bonds (whose rate of interest is now below the current market rate) will be less attractive to investors and they will attempt to sell them and move into investments paying a higher rate of return. Since the bonds can only be sold at a lower price, bond prices will fall until the fixed coupon payment (as a percentage of the new lower price) represents a higher rate of return equal to that currently on the market. This activity could well lead to the newspaper headline cited in the question. 6. The nominal rate of interest can never be negative because that would indicate that people were willing to pay someone to have use of their money, i.e., they want the nominal value or absolute size of their savings to decline over time, not increase. On the other hand, the real interest rate (the nominal rate minus the rate of inflation) can be negative if the rate of inflation exceeds the nominal interest rate. In this case, the nominal value of savings is increasing, but the purchasing power of those savings is declining because prices are rising at a faster rate than the rate at which savings are growing, i.e., the interest rate. If there are money markets in other countries which are paying a positive real rate of interest, then individuals should be attempting to move their funds out of negative real return investments in the home country to investments with the more attractive real rates abroad. In an integrated financial environment with no barriers to capital movements, funds would be shifted out of the country, which would place upward pressure on the nominal rate at home. Such pressure should continue until real interest rates are equalized. If negative real rates persist, this is a sign that there are barriers to capital movements and that the country is not well integrated into the world financial markets. 7. Eurodollar interest rate futures are sold in $1 million units. Therefore if one wishes a futures contract for more than $1 million, e.g., $10 million, one simply negotiates a contract containing 10 such units. If investors wish to hedge against interest rate changes for more than a three-month period, for example nine months, they would simply acquire a series of successive Eurodollar interest rate futures contracts which would cover the nine months in question. This could be done for an nine-month period starting in December 1997 by acquiring a March 1998 futures contract, a June 1998 futures contract and a September 1998 futures contract. When the March contract came to an end, it would be rolled over into the June contract. Similarly, when the June contract came to an end it would be rolled over into the September contract. The individual in question would thus be hedged against changes in the interest rate for the nine-month period ending on the September contract date. This type of collection of Eurodollar interest rate futures contracts is referred to as a Eurodollar Strip. 8. A characteristic of any futures contract is that gains or losses of the contracting parties are settled on a daily basis, and not on the final maturity date. Thus, for example in a currency futures contract, if a particular currency begins to depreciate (move away from the contract rate) the party agreeing to supply (taking a short position) the other (appreciating) currency at the contract rate must make up any change in the difference between the current rate and the contract rate on a daily basis. When the contract comes due, the supplier will have paid enough into the account such that the holder of the contract will be able to acquire the needed foreign exchange from the market on the contract date by using a combination of funds at the contracted rate and the additional funds provided by the seller of the contract. Steady and large movements away from the contract rate can thus ultimately result in cash flow problems for the seller of the contract. Similar problems can occur in interest rate futures contracts as well, the principal difference being that the daily margin pertains to deviations of the market rate of interest from the contract rate (rather than deviations in the exchange rate.). 9. A Eurodollar interest rate swap involves the exchange of interest rates by the two contracting parties for several periods in the future. This generally involves the exchange of a fixed rate by one party for a floating rate held by the other party, and is most often written in terms of LIBOR. This type of contract can benefit both parties in that a person holding a fixedrate loan cannot benefit from declines in the market rate of interest and thus might prefer to hold a variable-rate instrument. On the other hand, an individual with a flexible-rate loan might feel at risk because of potential increases in the interest rate and hence the cost of his loan. A swap thus enables the person who would prefer to take on more risk by switching from a fixed rate to a flexible rate to obtain the more preferred position and, at the same time, permits the holder of a floating-rate loan to reduce his interest rate exposure by obtaining a fixed rate without having to renegotiate the original loan. A “normal swap” involves the exchange of a fixed rate for a floating rate. A “basis swap” occurs when both sides are contracting a floating rate (a floating-floating swap). If the economic environment and or expectations should change, either or both contracting parties can contact a swaps trader and enter into a second swap arrangement. 10. In futures contracts, both the writer and the buyer of the contract can potentially lose, depending on what happens to the market interest rate. In the case of options contracts, the writer of the options contract bears all the risk associated with interest rate changes. This asymmetry is dealt with through the size of the up-front cost of the futures contract (the option price), which is paid by the purchaser of the options contract. The greater the risk, the higher the option price. 11. The growth in loan syndicates has fostered growth in international lending by reducing the credit risk to any one single lender, particularly in the case of very large loans to sovereign borrowers. In addition, syndication has resulted in a reduction in the time for processing loans, a decrease in the costs associated with international lending, and has facilitated the contracting of very large loans. In a loan participation syndicate, the principal or lead bank negotiates the loan instrument with the borrower and then enters into participation agreements with other banks (syndicates the loan). In this case the participating banks are not viewed as co-lenders. In the case of the direct loan syndicate, all the bank participants sign a common loan agreement and are legal co-lenders. 12. In this case, you would purchase a “call” at the strike price of 9250, since 10,000-9250 (equivalent to 1.000 - .925) reflects a 7.5 percent rate of interest. For this contract you would have to pay 54 basis points. Since each basis point is worth $25, a $1 million contract would cost (54)($25) or $1,350. A $6 million contract would thus cost a total of $8,100.