Valuation of a business, Part 3

advertisement

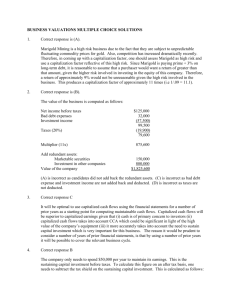

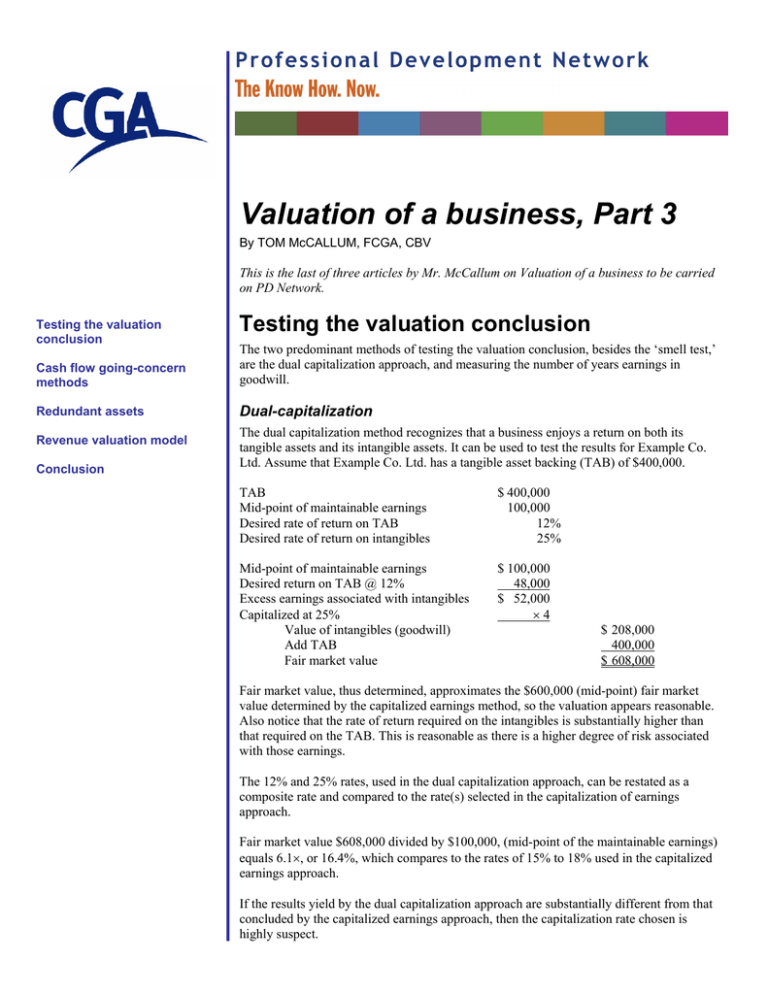

Valuation of a business, Part 3 By TOM McCALLUM, FCGA, CBV This is the last of three articles by Mr. McCallum on Valuation of a business to be carried on PD Network. Testing the valuation conclusion Testing the valuation conclusion Cash flow going-concern methods The two predominant methods of testing the valuation conclusion, besides the ‘smell test,’ are the dual capitalization approach, and measuring the number of years earnings in goodwill. Redundant assets Dual-capitalization Revenue valuation model Conclusion The dual capitalization method recognizes that a business enjoys a return on both its tangible assets and its intangible assets. It can be used to test the results for Example Co. Ltd. Assume that Example Co. Ltd. has a tangible asset backing (TAB) of $400,000. TAB Mid-point of maintainable earnings Desired rate of return on TAB Desired rate of return on intangibles $ 400,000 100,000 12% 25% Mid-point of maintainable earnings Desired return on TAB @ 12% Excess earnings associated with intangibles Capitalized at 25% Value of intangibles (goodwill) Add TAB Fair market value $ 100,000 48,000 $ 52,000 ×4 $ 208,000 400,000 $ 608,000 Fair market value, thus determined, approximates the $600,000 (mid-point) fair market value determined by the capitalized earnings method, so the valuation appears reasonable. Also notice that the rate of return required on the intangibles is substantially higher than that required on the TAB. This is reasonable as there is a higher degree of risk associated with those earnings. The 12% and 25% rates, used in the dual capitalization approach, can be restated as a composite rate and compared to the rate(s) selected in the capitalization of earnings approach. Fair market value $608,000 divided by $100,000, (mid-point of the maintainable earnings) equals 6.1×, or 16.4%, which compares to the rates of 15% to 18% used in the capitalized earnings approach. If the results yield by the dual capitalization approach are substantially different from that concluded by the capitalized earnings approach, then the capitalization rate chosen is highly suspect. Number of years earnings in goodwill The second test commonly employed is to measure the number of years earnings in the goodwill imputed by the capitalized earnings approach. Returning again to the Example Co. Ltd. illustration: Mid-point of fair market value TAB Goodwill Mid-point of maintainable earnings Number of years earnings ($200/$100) $ 600,000 400,000 $ 200,000 $ 100,000 2 Given the nature of the business, the industry, the risk, and so on, two years earnings in goodwill is believed reasonable. If this result yields a high number of years, then in all likelihood, but not necessarily, the business is over-valued. Cash flow going-concern methods There are two methods of cash flow approaches to the valuation of a business. These are the discounted cash flow and the capitalized cash flow methods. Each is discussed briefly following. Discounted cash flow (DCF) The DCF approach is principally used in valuations where cash flows are expected to vary widely from year to year or where the business will not have an infinite life, such as an extractive industry, and where cash flows are reasonably predictable. It is also used in the valuation of identifiable intangible assets such as patents, and copyrights where the cash inflows from rents, leases, and royalties are predictable. The DCF method is seldom employed in commercial, industrial, or service sector business valuations, but there are exceptions. Most notable exceptions are subscription-based businesses, such as insurance and cable television companies. While the DCF approach is conceptually a superior method, the difficulties inherent in projecting future cash flows, estimating residual values, and selecting an appropriate capitalization (discount) rate limit its general application. Also, very few closely-held small businesses prepare forecasts beyond perhaps, at best, one year. Even where the business has forecasts, those forecasts must be critically evaluated before they can be relied on. This introduces an element of uncertainty not present in the capitalized earnings approach. Exhibit 3 Discounted cash flow approach 14% discount rate Year After-tax Income 1 2 3 4 5 $ 100,000 75,000 140,000 200,000 175,000 Sustaining Non-cash Capital Outlays Re-investment Cash Flow $ 50,000 50,000 50,000 50,000 50,000 $ 15,000 15,000 25,000 30,000 30,000 $ 135,000 110,000 165,000 220,000 195,000 Residual value of business @ end of Year 5 Estimated @ Year 5 earnings capitalized at 14%, $1,250,000 Present Value Factor DCF .877 .769 .675 .592 .519 $ 118,395 84,590 111,375 130,240 101,205 545,805 .519 648,750 $ 1,194,555 $ 1,200,000 Rounded, say Valuation of a business, Part 3 • 2 In the foregoing DCF exhibit, sustaining capital re-investment represents the annual investment in capital assets required to sustain the present operations of the business. The amount is net of the present value of the income tax (called the “tax shield”) reductions available by claiming capital cost allowance. Also, no accounting for debt reduction is used. That approach will be ‘foreign’ to most accountants, but there is an assumption in the DCF method that debt will be replaced by debt. Capitalized cash flow approach Many investors consider cash flows as a major measure of a prospective investment’s suitability rather than net income determined through application of Canadian GAAP. Also, for some industries, cash flow — particularly where high rates (relative to accounting amortization rates) of capital cost allowance are allowed for income tax purposes — is the more relevant approach. The professional valuator frequently uses both the capitalized earnings and the capitalized cash flow approaches in estimating fair market value. Although each method offers advantages and disadvantages, the distinct advantage of the cash flow approach is its recognition of capital reinvestment, capital cost allowance, and the related income tax consequences, versus amortization (depreciation) accounting. Additionally, the problem of deferred taxes is virtually eliminated. The concepts and procedures are similar to those of capitalization of earnings and are best demonstrated by example. ABC LIMITED Fair market value (Capitalized cash flow approach) (,000s) Adjusted income before income taxes Add amortization (depreciation) Cash flow before income taxes Less income taxes at 20% Less sustaining capital reinvestment Less tax shield Discretionary cash flow after-tax Multiplier (capitalization rate 14.3%, 16.7%) $ 20 7 Add tax shield on existing undepreciated capital cost Fair market value Rounded, say Low High $ 100 50 $ 150 30 $ 120 $ 135 50 $ 185 37 $ 148 13 $ 107 ×7 $ 749 $ 25 9 16 $ 132 ×6 $ 792 50 $ 799 50 $ 842 $ 800 $ 850 Redundant assets Where a business has assets which are surplus to the operating needs of the business, these assets are considered redundant assets, and their value is additional to the capitalized earnings or cash flows value otherwise determined. Examples include items such as works of art, investment portfolios, excess cash or working capital, and retired equipment. Valuation of a business, Part 3 • 3 Assume, for example, that Private Co. Ltd. has not been distributing its earnings to its shareholders. This is often the case in a small closely-held business where the tax costs of the distribution outweigh the advantage, albeit a temporary one, of retaining profits. Private Co. Ltd. has a working capital ratio of 4:1, whereas the industry norm is 1.5:1, and the excess is mostly invested in a term deposit or GIC. Let us assume the excess working capital, represented in cash, is $150,000. The issue is how to account for this in determining value. First, the earnings, if any, on the redundant asset need to be removed from the measure of maintainable earnings (or cash flows). Second, the gross value of the asset needs to be removed from TAB. Adjusted earnings before considering non-operating income Less interest income Maintainable earnings $ 200,000 10,000 $ 190,000 TAB before considering redundant assets Less redundant assets TAB $ 450,000 150,000 $ 300,000 Without considering the existence of redundant assets we might have, based on the level of TAB, assigned a value of 6 × $200,000, or $1,200,000 to Private Co. Ltd. Now though, having reduced TAB to a lesser figure, we can assume there is more risk in the company and therefore a greater capitalization rate (lower multiple) is appropriate. Assume that to be 5×, which gives a value of $950,000 ($190,000 × 5). Note that in the first instance, interest income on the redundant asset was erroneously included in maintainable earnings. While the capitalized value of Private Co. Ltd.’s earnings is $950,000, this is not the fair market value of the company. The redundant asset — cash — is additional as it can be withdrawn from the company (by definition, without affecting the operations). The realizable value of the redundant asset is added to the capitalized earnings value. Realizable value is the amount net of any tax or sale costs that represents cash to the shareholder. If we assume some tax planning, an estimate of the tax costs might range from zero to 40%. Private Co. Ltd. Fair market value High Low Capitalized earnings Add realizable value of redundant assets Fair market value $ 950,000 90,000 $ 1,040,000 $ 950,000 150,000 $ 1,100,000 Failure to recognize the redundant asset and the associated income caused the initial valuation of $1,200,000 to be an overstatement. In any given set of circumstances, a failure to recognize redundant assets can also result in an understatement of value. The example used here also illustrates a valuation practice principle. Where there are known redundant assets, including hidden redundancies, as discussed in the next section, a valuator can attempt to account for these via a decrease in the capitalization rate (higher multiple), but generally the isolation of the redundant assets, along with the selection of a more appropriate capitalization rate based on the ‘true’ TAB, is the superior approach. Valuation of a business, Part 3 • 4 Hidden redundancies The foregoing section on redundant assets also provides a hint of another valuation concept used in the capitalization of earnings/cash flow approach. The business is assumed to have an optimal balance sheet, that is, an appropriate level of financing. Where the balance sheet is not optimal, and the business is overcapitalized, a hidden redundancy may exist. Note that while the excess working capital example in the above redundant asset section does present an overcapitalized balance sheet, the redundancy was not hidden. Generally, a hidden redundancy exists where long-term debt is disproportionately small when compared to capital assets and/or equity. Consider the following balance sheet: Current assets Capital assets $ 1,000,000 1,500,000 $ 2,500,000 Current liabilities Shareholder equity $ 800,000 1,700,000 $ 2,500,000 A review of industry norms, publicly available from a number of sources (e.g., Dun & Bradstreet’s Key Business Ratios, Industry Canada, Statistics Canada), indicates that this company could have additional debt of $700,000 and still be at the debt to equity level considered normal for its industry. How then to account for this overcapitalization in valuing the company? As the overcapitalization is a redundant asset, its value is excess to the going-concern value based on a capitalization of its earnings/cash flows. However, unlike the working capital overcapitalization example used in the redundant asset section, this overcapitalization cannot be realized without borrowing. TAB before considering redundancy Less additional borrowing (hidden redundancy) TAB $ 1,700,000 700,000 $ 1,000,000 Adjusted earnings before considering hidden redundancy Less interest on new debt, $700,000 × 8%, net of 20% tax Maintainable earnings Capitalized at 12.5% $ 200,000 44,800 $ 155,200 ×8 $ 1,241,600 600,000 $ 1,841,600 Add realizable value of redundant asset, say Fair market value, rounded $ 1,850,000 Without considering the hidden redundancy, the fair market value of the business might have been determined as $1,600,000, based on 8 × $200,000 — a serious undervaluation. Where a business is undercapitalized, that is, it is carrying too much debt, there will be a negative redundancy. The valuation approach is essentially just the opposite of that just presented. The required capital infusion will be applied to reduce debt. Consequently, maintainable earnings will increase and the capital infusion will be deducted from the resulting capitalized earnings/cash flows. Valuation of a business, Part 3 • 5 Revenue valuation models For some businesses, such as professional practices, a gross revenue valuation approach can be used. This approach requires a careful analysis of, among other things, the practice revenues, services performed, and the clientele or patients. The revenue model is based on the assumption that a professional practice is fairly standard and revenues of ‘x’ dollars should produce earnings of ‘y’ dollars. While the model is appealing because of its apparent simplicity, the reality is that it is very complex. This is because of the numerous judgements involved, and that the model varies depending on, among other things, whether the practice is urban or rural, its geographical site (which, and what part of a, province/territory), and whether there is a shortage or abundance of practitioners. Valuations based on revenue models should always be reconciled to values determined using the other generally accepted methods. In short, revenue models are extremely dangerous in the hands of the inexperienced. For example, accounting practices are generally said to have a goodwill value of one year’s revenue. In truth, that value can range anywhere from about zero to 150% of revenues. Conclusion As noted in Part 1 of this series, valuation is part science, part art, but mostly the latter. This is an introduction to the basics and many of the concepts, methods, and approaches have not been examined in depth. Items such as the capitalization rates, discount rates, tax rates, management salaries, liquidation costs, and assumptions used in these documents are for illustration purposes only and are not intended to represent actual appropriate selections. Additionally, matters such as special-interest purchasers, minority discounts, valuation of special or preferred shares, unusual liquidity issues, economic value-added determinations, and non-voting shares have not been addressed and are left to the reader to further research. J. Thomas McCallum, FCGA, CBV, began his tax career in 1967. He is currently based in Ontario and restricts his practice to business valuation and income tax consulting. He has conducted hundreds of seminars throughout Canada, Barbados, and the United States. Active in the Certified General Accountants Association, Tom is a past president of CGA Ontario. Valuation of a business, Part 3 • 6