Document 10309955

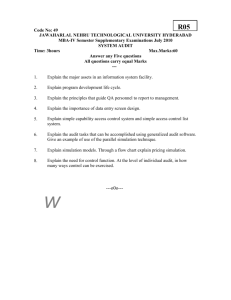

advertisement