Local Government Budgeting Toolkit Materials to Accompany Remarks of Michael Schaeffer

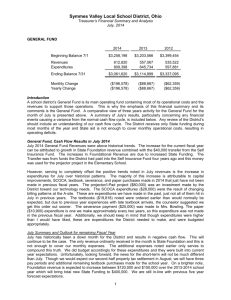

advertisement