SEX DIFFERENCES IN THE EXPERIENCE OF ANGER AND ANGER-RELATED EMOTIONS.

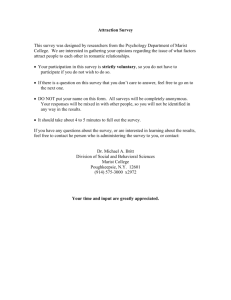

advertisement