Antenatal care: Components & Choices

advertisement

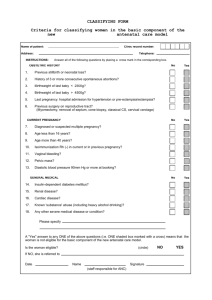

Antenatal care: Components & Choices By Dr. Rozilla Sadia Khan, Aga Khan University Hospital Antenatal care is a phenomenon of the twentieth century. When introduced in England, large number of clinics mushroomed overnight and a set pattern of care for women during pregnancy was established. This ritual pattern of care has been challenged to more tailor made regimens, in order to evaluate & treat women as individuals for any measurable health benefit. Unlike in the developed world, most young women initially seek any medical care at the commencement of a pregnancy, it provides a useful opportunity to evaluate, screen & educate them. The principles of antenatal care for women with uncomplicated pregnancies are to provide advice, education, reassurance and support; to address and treat the minor problems of pregnancy; to provide effective screening during the pregnancy; and finally, to identify problems as they arise. The Booking Clinic The first antenatal clinic visit, also called the ‘booking clinic’, is paramount in identifying those women with risk factors. Where a pregnancy is perceived as problem-free, a minimum level of care must be outlined, with the capacity to build on this as and when problems arise. Depending on the stringency of risk criteria, 19–50% of women will be identified as being without major risk at booking. Identification of risk factors A full history should be taken, during which risks relating to maternal disease, family history and previous pregnancy problems should be identified. It is vital that the history is recorded by someone who is able to recognize risk, and that appropriate measures are enacted when risks are identified. Antenatal care and education Antenatal care has been regarded a means of providing education and the opportunity to modulate behaviour in pregnancy. The extent to which this is true is limited, as women derive education from multiple sources, and are more likely to use other methods as a primary source of education, such as other female relations, the Internet. However, whilst it is a valuable opportunity to reinforce education, those women who have the most to gain are generally the least likely to utilize antenatal care effectively, especially in the early stages of pregnancy. Antenatal care and lifestyle Dietary advice is important in pregnancy, and supplementation with folic acid (400 mg daily) preconceptually and up to 12 weeks’ gestation reduces the risk of neural tube defects in the fetus. Advice on diet also plays a role in avoiding/treating minor ailments such as heartburn, constipation and haemorrhoids. Food-borne infections such as listeriosis and salmonella are important in pregnancy. Few prescribed and over-the-counter medicines have been established as safe to use in pregnancy, and should only be used where the benefit to the mother is greater than the risk to the fetus. As many as 30% of women suffer domestic violence during pregnancy. Domestic violence can have serious consequences, both to the mother and the fetus. Minor ailments of pregnancy Nausea and vomiting are common in early pregnancy, and women should be advised that most cases will resolve by 16–20 weeks’ gestation without medication. However, there are effective interventions (ginger, acupressure, antihistamines) available if required. Antacids can be used in women with troublesome heartburn. Varicose veins will not cause harm in pregnancy, and properly fitted compression stockings can improve the symptoms. Physiological vaginal discharge is common in pregnancy. If the woman is symptomatic, an infective cause should be investigated and treated as appropriate. Backache is also common; acupuncture, massage and physiotherapy may help. Clinical examination Auscultation for maternal heart sounds is vital in those with significant symptoms or a known history of heart disease. Such women will require cardiovascular examination during pregnancy. Formal breast examination by physician or self-examination is vital in detecting breast masses. Women should, however, be encouraged to report any new or suspicious lumps that develop, and, where appropriate, full investigation should not be delayed because of pregnancy. The risk of a definite lump being cancer in the under 40s is approximately 5%, and late-stage diagnosis is more common in pregnancy because of delayed referral and investigation. Weight Assessments The measurement of weight is important to identify women who are significantly under- or overweight. Women with a body mass index (BMI) [weight (kg)/height2 (m)] of <20 are at higher risk of fetal growth restriction and increased perinatal mortality. This is particularly the case if weight gain in pregnancy is poor. Intervention in terms of dietary advice and psychiatric help where eating disorders are a problem can be beneficial. Repeated weighing of underweight women during pregnancy will identify that group of women at increased risk for adverse perinatal outcome due to poor weight gain. In the obese woman (BMI430), the risks of gestational diabetes and hypertension are increased. Additionally, fetal assessment, both by palpation and ultrasound, is more difficult. Obesity is also associated with increased birth weight and a higher perinatal mortality rate The first recording of blood pressure (BP) should be made as early as possible in pregnancy. Hypertension diagnosed for the first time in early pregnancy (BP4140/90 on two separate occasions at least 4 h apart) should prompt a search for underlying causes, i.e. renal, endocrine and collagen-vascular disease. Although 90% of cases will be due to essential hypertension, this is a diagnosis of exclusion and can only be made confidently when other causes have been excluded. Urinary examination Screening of midstream urine for asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy is of proven benefit. The risk of ascending urinary tract infection in pregnancy is much higher than in the non-pregnant state. Acute pyelonephritis increases the risk of pregnancy loss/premature labour, and is associated with considerable maternal morbidity. Additionally, persistent proteinuria or haematuria may be indicators of underlying renal disease, prompting further investigation. Abdominal palpation Routine abdominal palpation at the antenatal visit is a crude screening tool for the assessment of growth of the developing pregnancy multiple pregnancy, failing pregnancy and wrong dates. Most women undergo ultrasound examination in the late first trimester, which is particularly important with reference to Down’s syndrome screening. Routine blood tests Women are now offered screening for a vast range of problems, both maternal and fetal. Many women have little idea of the range of tests they have undertaken, and the opportunity to discuss these arises in antenatal visits. Rubella Screening for rubella immunity should be offered routinely to all women. Susceptible women should be offered postpartum vaccination to protect future pregnancies. Two per cent of nulliparous and 1.2% of parous women will be found to be nonimmune. Non-immune women should be advised to avoid infected individuals, and any clinically suspected case paired sera are examined to detect infected women. In women who have been vaccinated previously, full immunity must be checked post-vaccination before this can be ensured. Syphilis Screening for syphilis continues to be offered to pregnant women as a routine test. Syphilis is uncommon, but as a treatable condition with major maternal and neonatal sequelae if undiagnosed, therefore screening will continue in some centers. Hepatitis B In the developed world various health bodies recommend universal screening for hepatitis B in pregnancy. About 21% of hepatitis B infections are due to mother-to-child transmission, and 95% of these can be prevented by passive and active immunization. Passive and active vaccination for at-risk infants is recommended, although the rates of full vaccination (three doses) are still not achieved in many cases. Full vaccination protects infants in 95% of cases against development of chronic hepatitis B infection, with the contingent risk of post-infectious hepatic cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) The incidence of HIV infected individuals is on the increase world wide, and not all those infected manifest all the clinical features in the early phase of infection. The evidence is now compelling that the mother-to-child transmission rates can be reduced from 26% to <2% with strategies including antiretroviral therapy, Caesarean section and avoidance of breastfeeding. Screening for fetal anomalies Strategies adopted for screening for fetal anomaly vary widely. These tests aim towards identifying anomalies that are incompatible with life, associated with increased morbidity and handicap, conditions treatable by intrauterine therapy, and those requiring postnatal investigation and/or treatment. Tests are divided into two major modalities, ultrasound screening and biochemical screening, and the two may be used together to increase the sensitivity of the tests. It is vital that women understand that these are screening tests, and will not detect every case of anomaly. Also, women need to understand that most so-called high-risk results will not mean that their baby is affected. Screening for Down’s syndrome Screening for Down’s syndrome can be performed during the first or second trimester. During the first trimester, biochemical screening at 10–14 weeks along with ultrasound nuchal translucency (NT) measurement is effective and provides an earlier diagnosis. The NT is a measurement of the subcutaneous space between the skin and the cervical spine in the fetal neck. It is increased in fetuses with a number of chromosomal, genetic and structural problems, including Down’s syndrome and congenital heart disease. In the second trimester, screening consists of a combination biochemical analysis performed at 16 weeks, even with the best tests, 30 invasive diagnostic tests must be performed to detect one case of Down’s syndrome. The test is very gestation specific, and if ultrasound confirmation of dates has not been performed, problems can arise. About 20% of women over 35 years of age can expect to fall into a high-risk category. Ultrasound Many women now routinely undergo ultrasound for pregnancy dating, early identification of multiple pregnancies. Accurate ultrasound assessment of dates has been shown to reduce the need for induction of labour for post-maturity. Additionally, ultrasound ascertainment of chorionicity in twin pregnancy is best achieved before 14 weeks’ gestation. The different patterns of fetal loss in monochorionic (Identical) as opposed to dichorionic (fraternal) twin pregnancies mean that increased surveillance can be offered in women with monochorionic twins between 18 and 24 Detailed fetal anomaly scanning Fetal ultrasound for fetal abnormality is offered to many women in the second trimester at approximately 18–20 weeks’ gestation. Fetal anomaly scanning reduces the overall perinatal mortality rate by allowing choice for termination of pregnancy. The outcome for some infants will be improved by the knowledge of a problem, e.g. some forms of congenital heart disease, gastroschisis. Planning for delivery is also vital, with preparation and, in some cases, transfer of antenatal care to specialist units becoming possible. In the case of severe disabling conditions or conditions incompatible with life, the choice of a termination of pregnancy is an important option for many couples, and fetal anomaly scanning does offer this choice. Screening for haematological disorders The most common cause of anaemia in pregnancy is iron deficiency. Over 90% of pathological anaemia in pregnancy is due to depleted iron stores and deficient iron intake. Even small decreases in iron will impact on iron-dependent enzymes in muscle, neurotransmitters and gastrointestinal epithelium. Exercise tolerance drops, and women feel fatigued. The normal level of haemoglobin in the first trimester is 11 g/dl, and 10.5 g/dl at 28–30 weeks’ gestation. Therefore, screening should be done at the booking visit, and at 28 and 36 weeks’ gestation. Women whose dietary iron intake is poor will benefit from iron supplements from early in pregnancy. Haemoglobin levels outside the normalrange should be investigated and treated as appropriate. Persistent anaemia should prompt investigation for haemoglobinopathy in any woman. Partner testing should be undertaken in any couple where the woman is affected. Red cell alloantibodies and prophylactic anti-D Screening for important red cell antibodies should be undertaken in all women early in pregnancy, and should be repeated in subsequent pregnancies even if women are found to be rhesus positive. Passive immunization of rhesus – D non immunized mothers at various stages in pregnancy can prevent immunization & pregnancy losses. In summary antenatal care has immense potential benefit for improving health, identification of problems in mothers at risk. Meeting both physical and psychological needs in pregnancy. A clear management plan must be identified for each individual with recognized risk. Women with problem-free pregnancies should be managed in a community setting to increase satisfaction and reduce intervention. Dr Rozilla Sadia Khan, M.R.C.O.G. is Senior Instructor, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology at Aga Khan University Hospital, Karachi, Pakistan website: www.aku.edu