POLITICAL ECONOMY RESEARCH INSTITUTE "Saving" Robert Pollin

advertisement

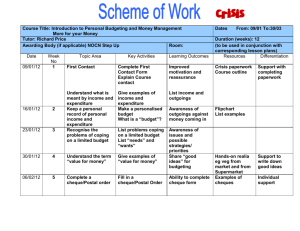

University of Massachusetts Amherst "Saving" POLITICAL ECONOMY RESEARCH INSTITUTE POLITICAL ECONOMY RESEARCH INSTITUTE Robert Pollin 2002 10th floor Thompson Hall University of Massachusetts Amherst, MA, 01003-7510 Telephone: (413) 545-6355 Facsimile: (413) 545-2921 Email:peri@econs.umass.edu Website: http://www.umass.edu/peri/ WORKINGPAPER SERIES Number 31 1 Entry on “Saving” for John King, Editor, The Elgar Companion to Post Keynesian Economics Robert Pollin Department of Economics and Political Economy Research Institute University of Massachusetts-Amherst Amherst, MA 01002, USA January, 2002 What is the relationship between saving behaviour in capitalist economies and their macroeconomic performance? This question is a hardy perennial in the history of economics, and one that has carried great theoretical and practical significance through its many revivals. It is easy to see why this is so, since any economy that aspires to long-term increases in productivity and average living standards must devise effective means of raising the quantity and quality of its capital stock. The role of saving is central to this process, though how exactly it exerts influence has long been a matter of contention. Debates on how saving behavior affects long-term growth and business cycles stretch back to those between Ricardo and Malthus on whether Say’s law of markets that ‘supply creates its own demand’ can be violated, thereby creating the possibility for ‘general gluts’ or depressions. The Keynesian revolution, of course, was also focused on this issue, as Keynes rebelled against the 1934 ‘Treasury View’ that higher saving rates were a necessary precondition for stimulating investment and lifting the British economy out of depression. Arguing against the intuitively appealing notion that an adequate pool of saving must exist before the funds for investment can be drawn, Keynes and Richard Kahn developed the concept of the multiplier to demonstrate the counterintuitive point that higher levels of saving will generate higher saving as well. Many of the most pressing policy concerns of today remain centered on the relationship between saving and macroeconomic performance. What is saving? The answer is not obvious. Moreover, answering the most basic questions about the impact of saving on macroeconomic activity—including whether saving rates 2 are rising or falling—depends on how one defines and measures the term (this discussion follows Pollin 1997b). Two standard approaches to measuring saving are as an increase in net worth and as the residual of income after consumption. As accounting categories, these two saving measures should be equal in value. But making this distinction raises a major question: when one considers the category of asset-specific saving, should the value of assets be measured at historical costs or market values? Only the historical cost measure is equivalent conceptually to residual saving. Measured at market values, asset-specific saving will of course fluctuate along with fluctuations in asset prices themselves. Another major issue is distinguishing gross saving, including depreciation allowances, and net saving, which excludes depreciation. In principle, net saving measures the funds available to finance economic growth, while gross saving would also include funds set aside for replacing worn out capital stock. In practice, however, depreciation allowances do not simply finance replacement. Rather, they are primarily used to finance investment in capital stock that represents some advance over previous vintages. As such, depreciation funds are also utilized to promote economic growth. What is the most appropriate definition of saving? In fact, for the purposes of economic analysis, there are legitimate reasons to examine each concept. There are three basic purposes for considering saving patterns by any measure. The first is to observe households’ portfolio choices, in which case asset-specific saving is obviously the only option. The second purpose would be to understand consumer behavior. Here we would want to measure consumption directly relative to income, making saving a residual. However, asset-specific saving at market values would also be important here insofar as it contributes to understanding consumer behavior. The third reason for measuring saving is with respect to examining its role in determining credit supply, i.e. the source of funds available to finance investment and other uses of funds. This role for saving is clearly the primary consideration among analysts seeking to understand the relationship between saving and macroeconomic performance. In fact, however, the connections between any given measures 3 of saving, the provisioning of credit, and overall rates of economic activity are quite loose. We can see some indication of such loose connections through the table below on the U.S. economy. TABLE BELONGS HERE The first three rows of the table show annual figures on net, gross and net worth saving in the U.S. relative to nominal GDP between 1960 – 2000. The data are grouped on a peak-to-peak basis according to National Bureau of Economic Analysis business cycles. The last two rows of the table show, respectively, measures of credit supply and overall activity: first the ratio of total lending in the U.S. economy relative to gross private saving, then the average annual growth rate of real GDP. To begin with, the table shows substantial differences in the cycle-to-cycle behavior of the three saving ratios. For example, between the 1970s and 1980s cycles, the net saving ratio fell from 9.8 to 8.9 percent, the gross saving ratio rose from 18.4 to 19.1 percent, and the net worth ratio fell from 39.5 to 32.4 percent. Meanwhile, between these same two cycles, the lending/saving ratio rose sharply from 86.9 to 106.1 percent, while the rate of GDP growth fell from 3.3 to 2.9 percent. At the very least, one can conclude from these patterns that we cannot take for granted any analytic foundation through which we assume a simple one-way Pre-Keynesian causal connection whereby, as James Meade (1975) put it, ‘a dog called saving wagged its tail labeled investment’ instead of the Keynesian connection in which ‘a dog called investment wagged its tail labeled saving.’ The pre-Keynesian orthodox view held that the saving rate is the fundamental determinant of the rate of capital accumulation, because the saving rate determines the interest rate at which funds will be advanced to finance investment. Keynes’s challenge to this position constituted the core of the ensuing Keynesian revolution in economic theory. Nevertheless, what we may call the ‘causal saving’ view was nevertheless restored fairly quickly to its central role in the mainstream macroeconomic literature. 4 Despite neglect among mainstream economists, the ‘causal investment’ perspective has advanced substantially since the publication of Keynes’s General Theory (1936). One major development has been precisely to establish a fuller understanding of the interrelationship between saving, financial structures, and real activity. This has brought recognition that the logic of the causal investment position rests on the analysis of the financial system as well as the realsector multiplier-accelerator model. Of course, the multiplier-accelerator analysis is the basis for the ‘paradox of thrift’, that is, low saving rates (saving as a proportion of income) can yield high levels of saving and vice versa when real resources are not fully employed. However, considered by itself, the multiplieraccelerator analysis neglects a crucial prior consideration: that the initial increment of autonomous investment must be financed, and the rate at which financing is available will influence the size of this investment increment and the subsequent expansion of output, income and saving. Kaldor (1960) was an early critic of the multiplier-accelerator causal investment position, and his argument was revived by Asimakopulos (1983). Their critique focuses on the interim period between an autonomous investment increase and the attainment, through the multiplieraccelerator process, of a new level of saving-investment equilibrium. The Kaldor-Asimakopulos position is that, as a general case during such interregnum periods, intermediaries could not be expected to accept a reduction in liquidity without receiving an interest rate inducement to do so. Rather, for intermediaries to supply an increased demand for credit would require either a rise in interest rates or a prior increase in saving. As such, low rates of saving again yield high interest rates and a dampening of investment—an argument, in other words, that returns us to the causalsaving position. In fact, Keynes himself addressed this issue, working from his theory of liquidity preference and interest rate determination. But this dimension of his argument is far less well- 5 known than the consumption function and multiplier analysis, at least in part because it is less fully developed in the General Theory itself. Holding the level of saving constant, Keynes argued that the banking system—private institutions as well as the central bank—was capable of financing investment growth during the interregnum period without necessarily inducing a rise in interest rates. That is, as he put it, ‘In general, the banks hold the key position in the transition from a lower to a higher scale of activity,’ (1973, p. 222). Keynes based his position on a central institutional fact, that private bansk and other intermediaries, not ultimate savers, are responsible for channeling the supply of credit to nonfinancial investors. The central bank can also substantially encourage credit growth by increasing the supply of reserves to the private banking system, thereby raising the banks’ liquidity. But, even without central bank initiative, the private intermediaries could still increase their lending if they were willing to accept a temporary decline in their own liquidity. The reason the that the fall in intermediaries’ liquidity would be only temporary is that liquidity would rise again, even before the completion of the multiplier, when the recipients of the autonomous investment funds deposited those funds with an intermediary. Moreover, the completion of the multiplier process would mean that an increase in saving equal to the investment increment had been generated. Overall, then, it is through this chain of reasoning that Keynes reached what he called ‘the most fundamental of my conclusions within this field,’ that ‘the investment market can become congested through a shortage of cash. It can never become congested through a shortage of saving,’ (1973, p. 222). This more fully developed Keynesian position emphasizes clearly the central role of financial institutions in establishing the relationship between saving and macroeconomic activity. More recent literature has developed this idea in several directions (see the contributions in Pollin 1997a). Other researchers have broadened further this investigation as to the relationship between saving, institutional structures and macro activity. Indeed, in the 1990s a substantial literature developed arguing that financial systems that channeled savings within a tighter 6 regulatory structure tended to outperform economies in which capital markets operated more freely (Pollin 1995 reviews this literature). Countries categorized as having more tightly regulated ‘bank-based’ financial systems were Germany, France, Japan and, among the less developed Asian countries, South Korea. The U.S. and U.K. represented the less regulated ‘capital marked-based’ system. But by the mid-1990s, the debate over the relative merits of these systems was short-circuited by two factors: first the stock market bubble in the United States, which lent temporary credence to the idea that capital-market based systems could operate more effectively; and second, the global ascendance of neoliberal economic policies in economies such as Japan, France and Korea, contributing, in turn, to greater economic instability in these economies in the late 1990s. But a restoration of this line of research on alternative financial institutional environments will be critical for developing new policy regimes that can promote more stable as well as more egalitarian growth prospects. More broadly within the realm of policy, there always have been clear important normative issues at play in the debates over saving behavior. The agenda following from a causal saving perspective consists of seeking to raise national saving rates through measures such as providing preferential tax treatment to capital income, eliminating government deficit spending. or even paying off completely outstanding government debts. These will normally also generate a less equal distribution of income. Building from a causal investment analytic framework points to policy approaches that directly encourage higher investment while also promoting egalitarian distributional outcomes. Such measures would include increasing aggregate demand and employment through fiscal and monetary interventions or more equal income redistribution, or, through various institutional reforms, giving preferential access to credit for productive private investment relative to unproductive speculative expenditures. The policy ideas that flow from a causal investment perspective are committed to utilizing most effectively the interconnections observed in research between growth, stability, and distributional equity. 7 References Asimakopulos, A. (1983) “Kalecki and Keynes on Finance, Investment and Saving,” Cambridge Journal of Economics, 7, pp. 221-33. Kaldor, Nicholas (1960) “Speculation and Economic Activity,” (1939) in Essays on Economic Stability and Growth, London: Gerald Duckworth & Co. Ltd., pp. 17-58. Keynes, John Maynard (1936) The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, New York: Harcourt Brace. Keynes, John Maynard (1973) “The ‘Ex Ante’ Theory of the Interest Rate,” (1938) in The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes, vol. 14, London: Macmillan. Meade, James (1975) “The Keynesian Revolution,” in M. Keynes ed., Essays on John Maynard Keynes, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Pollin, Robert (1995) “Financial Structure and Egalitarian Economic Policy,” New Left Review, NovemberDecember, pp. 26-61. Pollin, Robert ed. (1997a) The Macroeconomics of Saving, Finance and Investment, Ann Arbor MI: University of Michigan Press. Pollin, Robert (1997b) “Financial Intermediation and the Variability of the Saving Constraint,” in R. Pollin ed., The Macroeconomics of Saving, Finance and Investment, Ann Arbor MI: University of Michigan Press, pp. 309-366. 8 Saving Rates, Credit Supply and GDP Growth for the U.S. Economy (in percentages) 1960-69 1970-79 1980-90 1991-2000 Net Private Saving/GDP 9.6 9.8 8.9 6.3 Gross Private Saving/GDP 17.1 18.4 19.1 16.4 Net Worth Private Saving/GDP 25.2 35.2 32.4 30.5 Total Lending/ Gross Private Saving 60.5 86.9 106.1 106.4 Real GDP Growth 4.4 3.3 2.9 3.2 Sources: U.S. National Income and Product Accounts; U.S. Flow of Funds Accounts. Note: For brevity, two sets of cycles—1970-73/1974-79 and 1980-81/1982-90—have been merged.