ETHNOMETHODOLOGY: A CRITICAL REVIEW

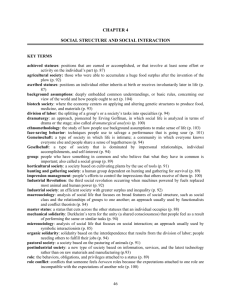

advertisement