Tax Planning and Management Considerations for Farmers in 2000

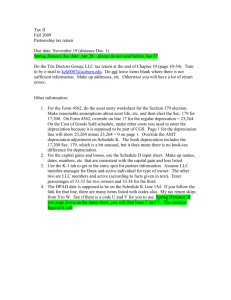

advertisement