Document 10296887

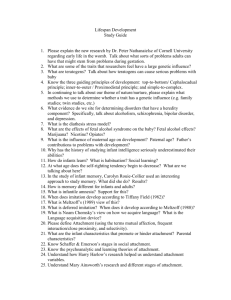

advertisement