1 I. Introduction II. What is Stress?

advertisement

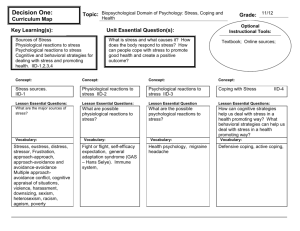

1 Psychology 3460: Stress and Disease I. Introduction II. What is Stress? A. Response 1. Fight of flight response 2. General adaptation syndrome B. Stimulus C. Transactional model D. Multidimensional nature of stress III. Stress and Health A. Animal models B. Human models IV. How is Stress Related to Disease A. Health-related behaviors B. Cognitive / Physiological processes V. Moderators of Stress A. Coping styles B. Control C. Personality D. Social Support VI. Managing Stress A. Biofeedback B. Exercise C. Progressive relaxation D. Meditation 2 10/31/04 I. Introduction. II. What is Stress? Response. Historically, researchers defined stress as a response by focusing on the organism’s physiological reactions to threat. In the late 1920’s, Walter Cannon advanced the notion that in the face of threat, there is a general sympathetic discharge to cope with the threat (i.e., the fight or flight response). General adaptation syndrome. (OVH) In the 1950’s, Hans Selye extended Cannon’s flight or fight model by examining the process of our reactions when confronted with a threat, especially a chronic one. Phase 1 is the alarm reaction characterized by increased ANS activity Phase 2 is resistance characterized by increased pituitary-adrenal activity Phase 3 is exhaustion characterized by decreased pituitary-adrenal activity and eventual system failure. Stimulus (stressors). One alternative approach is to view stress as a stimulus or stressor. One example is to examine major life events. (OVH) The Holmes-Rahe social readjustment scale has a rank ordering of major life events such as death of a spouse (1), son or daughter leaving home (23), and minor violation of law (43). An additional approach is to focus not on major events but on the daily hassles that we all experience. Hassles are defined as the irritating, distressing, and frustrating demands that characterize everyday transactions with our environment. Some evidence suggests that hassles may predict mental and physical health more than major life events in the long-term. One critique of this approach is that although some events are universally stressful, why do people often react differently to the same stressor. Transactional model. (OVH) The contemporary view is stress as a transactional process between the person and the environment. Emphasis is placed both the on the stimulus and our interpretation or appraisal of that event. Lazarus and Folkman define stress as a condition in which an event is appraised as taxing or exceeding our resources and/or well-being. There are two types of appraisal: primary appraisal is one’s assessment of potential danger, whereas secondary appraisal is concerned with the evaluation of one’s coping resources. III. What is the Relationship Between Stress and Health? 3 Animal models. Manuck et al. (1983) found that monkeys who showed the greatest stress response also developed greater coronary artery atherosclerosis. Rats exposed to uncontrollable stress developed larger cancerous tumors. Mice exposed to stress develop a poorer antibody response to challenges. Human studies. Experimentally induced psychological stress associated with changes in cardiovascular function that may be associated with disease. Epidemiological studies suggest that stress may be associated with both the development and exacerbation of disease. In one of the largest studies of its kind, the INTERHEART study found that across 52 countries using almost 25,000 participants, stress from work and home was associated with an increased risk for having a heart attack. Studies of naturally occurring stressors, such as the OSU caregiver research project have found that the chronic stress of caregiving is associated with a down-regulation of the immune system compared to demographically similar control groups. In addition, such caregivers also had more days of infectious illnesses. (OVH) In an attempt to examine an ecologically valid outcome, Cohen et al. (1991) infected subjects with the common cold virus and quarantined them over a 9 day period. Results revealed that psychological stress was associated with increased infection rates is a dose response manner. IV. How is stress related to disease. Health behaviors. Earlier in the course, we talked about how health behaviors such as smoking, alcohol consumption etc. can influence physical health. People under stress often change their health behaviors. For instance, stress is sometimes associated with increased alcohol and drug abuse. Therefore, some of the influence of stress on health may be due to its effects on health behaviors. Direct Effects. Stress may also influence cognitive and brain processes that lead to direct physiological changes that subsequently increases vulnerability to stress. Stress components. There are at least four stress components that may increase risk for disease. Exposure refers to the number of stressors that an individual experiences, reactivity refers to the strength of an individual’s physiological reaction to any given event, whereas recovery refers to the how long it takes an individual to return to “baseline” following stressful events. A final perspective is on restorative processes that serve to refresh or repair the organism (e.g., cellular damage) because stress may directly impede our ability to perform these functions (e.g., disturbed sleep, impaired wound healing). V. Moderators of stress. Coping responses. (OVH) There is a distinction between problem-focused vs. emotionfocused coping. Problem focused coping is concerned with problem solving aimed at altering the source of stress, whereas emotion focused coping is aimed at reducing the emotional distress of the situation. Problem-focused strategies most effective when one has potential control over the 4 stressor. Emotion-focused strategies most effective if the stressor is of relatively short duration and of little consequence. Overall, individuals who are most flexible in utilizing these coping strategies may be best off. Perceived control. All in all, however, control appears to foster adjustment to stress. For instance, controllable stress is not nearly as bad as stress that is uncontrollable (see Glass study on predictable vs. unpredictable noise). In one interesting study, Langer and Rodin (1977) instilled a sense of control in older nursing home residents. Short-term analyses revealed that individuals in the control condition were happier and engaged in more social activities than subjects not given control. More importantly, long-term analyses revealed an impressive effect on mortality about 18 months later: only 15% of control subjects died whereas 30% not given control had died. Personality. The Type A behavior pattern is characterized by extreme competitive striving for achievement, a sense of time urgency, hostility, and aggression. Interest in this personality trait was fueled by research from the Western Collaborative Group Study that found that Type A individuals were more than two times more likely to develop CHD compared to their Type B counterparts. Recent reviews have indicated that one component may be especially unhealthy: hostility. Hostility is a personality trait characterized by negative belief in others, feelings of distrust. Reviews have indicated that hosility is most strongly associated with risk for all cause mortality. We all know people who tend to look at the bright side of things, despite problems and obstacles. Scheier & Carver have found that optimistic people tend to be characterized by better psychological well-being. In addition, they appear to recover faster following coronary surgery. Finally, the flip-side of optimism is pessimism and it has been related to poorer health in a longitudinal study spanning about 35 years. A common mechanism perhaps underlying all of these personality processes are the schemas that guide information processing in these individuals. For instance, we know that schemas tend to be confirmatory. As a result, hostile individuals are more likely to see interpersonal betrayal in their lives, whereas optimistic individuals do just the opposite. Social support. (OVH) There is an impressive body of literature indicating that individuals who are more socially isolated or whose quality of social relationships are poor are less healthy (both psychologically and physically) and more likely to die. (OVH) Our important social relationships can influence stress in a variety of ways. Close network members can provide tangible support (e.g., money, lend us their car), informational support (e.g., how to study for an exam, what that cold sore might mean), and emotional support (e.g., help us feel better about ourselves – its that person’s loss because you’re a great person). One needs to carefully 5 match the type of support with the situation if not an attempt to be supportive may also turn into a source of stress for both parties. VI. Managing stress. Biofeedback. Although progressive relaxation and meditation tend to be quite general, biofeedback focuses on specific physiological systems by providing a form of feedback on that systems activity. For instance, a person may receive feedback in the form of an increasing tone whenever heart rate increases. The assumption is that the feedback will allow and individual to discriminate these changes and learn how to control it. In general, the results of biofeedback have been promising including effects on muscle pain, tension headaches, and hypertension. Exercise. It also appears as if exercise can help individuals cope with stress. In particular, a moderate amount (not exhaustive) of exercise has been linked to better health in the face of stress. In one study, Brown and Siegel (1988) found that high school girls who reported a high level of life stress showed poorer health. The best effects of exercise seem to be obtained with (a) sustained heavy breathing without exhaustion, (b) last between 20 min to 2 hrs, (c) engaged 3 or more times per week. Meditation. Meditation comes in many forms but what they share is a conscious attempt to focus attention in a nonanalytical way and an attempt to not dwell on ruminating thoughts. Focus is directed away from the thoughts and on the process by which thoughts flow in and out of mind. Meditation has helped people deal with phobias and anxieties and also appears to influence physiological processes such as reduced heart rate, oxygen consumption, and blood pressure. There are several important components to meditation. First, one needs to find a relatively quiet environment and assume a comfortable position. Second, one may choose a mental device that provides a constant environment (e.g., mantra or word, breathing). Third, one needs a passive, uncritical attitude. During meditation you will find interruptions creeping into your concentration. Try to maintain a passive attitude and let these interruptions flow in and flow out of your mind, try not to fight it too much. Also, try not to do this just before bedtime as it may make you even more alert and awake. Progressive relaxation. In this technique, a person is taught to relax by tensing and then releasing specific muscles. This induces relaxation but also teaches the person to identify early signs of muscular tension. Progressive relaxation has been shown to increase psychological well-being but also appears to have effects on physiological processes as well. For instance, it appears to have positive effects on hypertension and muscle tension headaches and immune system functioning.