CHAPTER XV

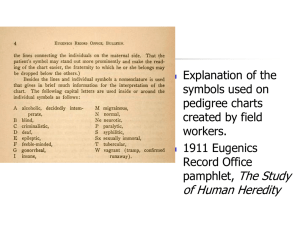

advertisement