IFRS vs. US GAAP: A Sixty Minute Waltz in...

IFRS vs. US GAAP: A Sixty Minute Waltz in the Classroom

Diane A. Riordan*

Email: Riordada@jmu.edu

Michael P. Riordan*

Email: Riordamp@jmu.edu

*Both Professors of Accounting at James Madison University

Abstract

Regulators in more than 100 countries now allow or require the use of international accounting standards (IFRS) when preparing financial reports for certain companies. The

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has announced a “roadmap” project towards U.S. adoption of IFRS. In this paper we make suggestions for incorporating significant aspects of international standards in the accounting classroom.

IFRS vs. US GAAP: A Sixty Minute Waltz in the Classroom

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) now allows foreign companies trading on U.S. stock exchanges to report financial information using International

Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) without the former requirement of reconciling to

U. S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (US GAAP). U. S. regulators are considering whether IFRS should be allowed for reporting by U.S. companies as well [9].

On August 27, 2008, the SEC issued a proposed “roadmap” towards the U.S. adoption of

IFRS [8]. In this business environment, accounting education is among the institutions now preparing for the integration of IFRS.

“Waltz” is used in our paper’s subtitle because the word brings to mind the frenzied pace of “The Minute Waltz.” As instructors, we have “just a minute” to expand our syllabus to accommodate a second set of standards. Like the waltz, which was seen as a threat to the dancing profession due to its simplicity when first introduced [4], the popularity and increasing adoption rate of IFRS threaten to devalue much of what we know. More than

100 countries now permit or require the use of IFRS [5].

Anticipating the demand for integration into the accounting curricula, we have formulated a framework for educators to communicate the essential differences between

IFRS and US GAAP in a short amount of time. Our approach is developed from the history and underlying principles of these two accounting frameworks. By introducing the topic of IFRS with these simple reference points, students can better understand the competing treatments sometimes offered by the two frameworks.

Brief History of the Origin of the Two Sets of Standards

IFRS were first developed in an environment in which the standards were not required by regulators. The predecessor to the current International Accounting Standards Board

(IASB) was the International Accounting Standards Committee (IASC). The IASC’s main activity from 1973 to 1988 was the issuance of 26 generic International Accounting

Standards (IASs), many of which allowed multiple options [1].

To attract varied interests to the same accounting framework, international accounting standards were designed to be flexible and are principle-based. These standards even have earned the label “lowest common denominator” [1]. Evidence of this flexibility is provided in the various benchmark and alternative treatments that still remain within some of the standards. As the primary example, historical cost is the benchmark for the valuation of property, plant and equipment, whereas current valuation is an acceptable alternative for valuation under IFRS [IAS 16].

US GAAP, on the other hand, has been derived since the Great Depression era by a profession with the goal of protecting investors through conservative accounting practices. Its rule-based construction also may operate to provide comfort to a profession that operates in a highly litigious environment. In the following paragraphs we provide examples of flexibility, conservatism, rules and principles.

The following example illustrates flexibility vs. conservatism. IFRS allow the recovery of value in connection with inventory write-downs (IAS 2) and other assets (IAS 36).

Although both US GAAP and IFRS require the write down of these assets, only IFRS allows a subsequent increase for recoveries in value. This restrictive treatment under US

GAAP may be attributed to conservatism.

The following example illustrates rules vs. principles. Under US GAAP leases (defined at FASB 13) are capitalized (a) if the lease life exceeds 75% of the life of the asset ; or (b) if there is a transfer of ownership to the lessee at the end of the least term; or (c) if there is an option to purchase the asset at a bargain price at the end of the least term or (d) if the present value of the lease payments, discounted at an appropriate discount rate, exceeds 90 percent of the fair market value of the asset . This treatment is rule-based in contrast to IFRS which relies on the principle of whether a “major part” of the asset or

“substantially all the fair value of the leased asset” will be consumed (IAS 17) rather than consumption based on set percentages (e.g. 75%, 90%). Emphasis in the preceding paragraph has been supplied.

Under IFRS a lease is a capital lease rather than an operating lease (a) if the lease transfers ownership of the asset to the lessee by the end of the lease term; or (b) if the lessee has the option to purchase the asset at a price less than fair market value; or (c) if the lease term is for the major part of the leased asset’s economic life; or (d) if the present value of minimum lease payments at the inception of the lease is equal to substantially all the fair value of the leased asset; or (e) if the leased asset is of a specialized nature such that only the lessee can use it.

A similar example (based on percentages vs. undefined terms) can be provided in a comparison for the rules of consolidation. When students recall the respective histories of the frameworks, specific differences become more meaningful to them. Students can begin to categorize on their own many of the various treatments through a process of correlating the detail in the specific standard with the origin of the respective frameworks.

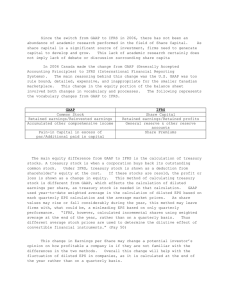

A Comparative List

In addition to introducing the topics with a brief history of the development of the standards and resulting principles, we recommend that novices develop their own list of key differences as a first step in their mastering and presenting the IFRS framework. See an example of the working document that we have created which we present as Exhibit 1.

The list can be updated as treatments change, and we have had to change it each year.

We recommend drafting the list in the form of comparative side-by-side financial statements. This approach lends itself to the instructor summarizing by illustrating reconciliation between the two frameworks. The reconciliation can take the form of adjustments as they would appear in the footnotes and disclosures following an actual set of financial statements.

EXHIBIT 1

LIST OF KEY DIFFERENCES TO BEGIN MASTERING IFRS vs. US GAAP

PARTIAL BALANCE SHEET

INVENTORY

PROPERTY

SELF-CONSTRUCTED PROPERTY

U.S. GAAP

Lower of Cost

Or Market*

Historical

Acquisition

Cost

Historical

Acquisition

Cost **

IFRS

Lower of Cost

Or Market* and **

No LIFO valuation

Requires

Capitalization Benchmark of Interest for Interest Expense

Expense

Expensing is

(Allows

Capitalization)

To converge in 2009 to US treatment

LEASES

“substantially all”

INTANGIBLES:

ACQUIRED PATENT Capitalize FMV Capitalize

FMV**

GOODWILL* **

Capitalize

Per Rules

(%)

Capitalize

Capitalize

Per Principles

“major part”

Capitalize

NEGATIVE GOODWILL

SELF-DEVELOPED PATENT

Extraordinary

Item in I.S.

Income Item

Expense Capitalize

Development Development

Costs Costs

HYBRID FINANCIAL

INSTRUMENTS Not bifurcated into debt vs. equity

Bifurcated

Exhibit 1 Continued

PARTIAL INCOME STATEMENT

U.S. GAAP IFRS

INCOME

REVENUE ITEMS

Extraordinary items reported in separate section

No extraordinary item reporting - disclosure

Completed contract allowed

Completed contract not allowed

EXPENSES By function, e.g. By function or

COGS, Adm, Selling nature, e.g. materials, salaries

ADVERTISING Policy choice Capitalize

*US GAAP and IFRS differ when defining “market” values for inventory.

**Reported values of these assets may be subject to upwards revaluation only under

IFRS.

***Test value for impairment under both U.S. GAAP and IFRS and expense as experienced. Recovery of impairment only allowed under IFRS.

Illustrating a Reconciliation from IFRS to US GAAP

A simple reconciliation can provide the conclusion to any one of the comparisons presented in the partial balance sheet and income statement. We present the reconciliation between IFRS and US GAAP required for the revaluation of plant and equipment.

As stated under IFRS

Net Income Shareholders’

Equity

$100,000 $1,000,000

US GAAP Adjustment

(A) Reversal of depreciation 10,000 200,000

(B) Reversal of revaluation

Surplus for fixed assets . 0 (700,000)

As stated under US GAAP $110,000 $ 500,000

Students are then asked to explain why Adjustment A results in an increase to the reported net income (increase of $100,000 to $110,000); why the increase to

Shareholders’ Equity is greater than the increase in net income ($10,000 vs. $200,000); and which equity account is affected by the adjustment in A. (Answer: Retained

Earnings)

Summary

In the U.S., teaching some details of both standards is currently a worthwhile learning objective. The U.S. roadmap for convergence set forth a view that IFRS and US GAAP could coexist in the global marketplace [6]. Although there are projects underway to converge the two frameworks, this goal is becoming more difficult as existing IFRS are being modified in order to arrive at a body of standards viewed as “acceptable for use in

Europe” [9].

It is important to acknowledge that convergence is occurring between the two frameworks. For example, IFRS now treats Goodwill with annual testing for impairment and will soon adopt capitalization of interest expense during the construction of longterm projects—both required in the U.S. And the U.S. has adopted aspects of IFRS’s approach to share-based payments as compensation. Under the SEC’s most recent roadmap [8] it is also possible that IFRS will replace US GAAP for certain companies as announced in that timetable for change.

The approach we have described in our paper helps instructors to begin “the dance” of

IFRS and US GAAP in their classrooms. Both standards are significant in the preparation of financial information, and students will have to deal with both of them in their professional lives for some time.

Additional Differences between IFRS and US GAAP

Reduced disclosure of contingencies is permitted under IFRS if disclosure would be severely prejudicial to an entity’s position in a dispute with another party. No similar provision to that allowed under IFRS exists under US GAAP. This difference is another example of the operation of the conservatism principle in the U.S.

In U.S. segment reporting (FASB 131) disclosure follows the same lines as reporting for internal control. IFRS (IAS 14), on the other hand, emphasizes product and geography.

The U.S. standard requires identification of the factors in identifying segments, whereas

IFRS do not so require. The U.S. does not require the reporting of liabilities by segment, whereas IFRS do require liabilities to be disclosed. IFRS is converging to U.S. GAAP after 2009.

The previous discussion is presented based on our understanding from our reading of the

Doupnik et al. text [1] and E&Y Basic Guide Fall 2007 for classroom use Spring 2008

[2].

REFERENCES

1 Doupnik, T. and H. Perera, International Accounting, Boston: McGraw-Hill Irwin,

2007

2 Ernst & Young, U.S. GAAP vs. IFRS: The Basics, 2007

3 Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). Selected standards from US GAAP, including FASB 13 and 131

4 http://www.centralhome.com/ballroomcountry/waltz.htm accessed 4/17/08

5 http://www.iasplus.com accessed 4/17/08

6 International Accounting Standards Board (IASB). A roadmap for convergence between IFRS and U.S. GAAP 2006-2008 at http://www.iasb.org

archives accessed

11/10/08

7 International Accounting Standards Board (IASB). Selected standards from

International Financial Reporting Standards including IAS 2, 14, 16, 17, 36

8 Sogoloff, R. Madla, R. and S. Wolfe, Deloitte & Touche LLP, “Heads Up,” August 28,

2008, Vo. 15, Issue 33

9 Street, D. L. and C. L. Linthicum, IFRS in the U.S.: It May Come Sooner Than You

Think: A Commentary, Journal of International Accounting Research , Volume 6, No. 1,

2007