M C O

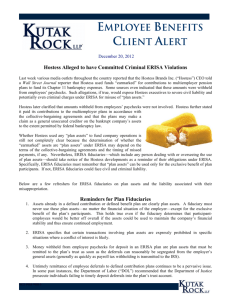

advertisement