Relationship of Child Psychopathology to Parental Alcoholism and Antisocial Personality Disorder

advertisement

Relationship of Child Psychopathology to Parental

Alcoholism and Antisocial Personality Disorder

SAMUEL KUPERMAN, M.D .. STEVEN S. SCHLOSSER, MAT., ]AMA LIDRAL, BA,

AND

WENDY REICH, PH.D.

ABSTRACT

Objective: To evaluate the contributions of familial factors, including parental diagnoses of alcoholism andlor antisocial

personality disorder (ASPD), to the risk of developing various child psychiatric diagnoses. Method: Four hundred sixtythree children and their biological parents were interviewed with adult and child versions of the Semi-Structured

Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism. Demographic and psychiatric data were compared across 3 groups of children on the basis of the presence of parental alcoholism and ASPD (no other parental diagnoses were examined).

Generalized estimating equations analyses allowed the inclusion of multiple children from each family in the analyses.

Results: Among offspring, parental alcoholism was associated with increased risks for attention-deficit hyperactivity dis-

order, conduct disorder (CD), and overanxious disorder. Parental alcoholism plus ASPD was associated with increased

risk for oppositional defiant disorder. Dysfunctional parenting style was associated with increased risks for CD, alcohol

abuse, and marijuana abuse. Low family socioeconomic status was associated with increased risk for CD. Conclusions:

Parental diagnoses of alcoholism and ASPD were associated with increased risks for a variety of childhood psychiatric

disorders, and dysfunctional parenting style was associated with the diagnoses of CD, alcohol abuse, and marijuana

abuse. J. Am. Acad. Child Ado/esc. Psychiatry, 1999, 38(6):686-692. Key Words: childhood psychopathology, genetics,

alcohol, antisocial personality disorder, children of alcoholic parents.

The rate of behavioral probJems in children of alcoholics

(COAs) seems increased compared with the rate ofbehavioral problems in children whose parents are not alcoholic. West and Prinz (1987) reported an increased

frequency of delinquency, truancy, social inadequacy, and

somatic problems. Roosa et al. (1988) and Tubman

(1993) each stated that COAs have more anxiety and low

mood symptoms than children whose parents are not

alcoholic. Connolly et aI. (1993) reported that COAs have

lower verbal and reading scores and have more schoolrelated behavior problems at age 9 and more home-related

problems at age 13. Finally, COAs begin drinking at an

earlier age (Fergusson et al., 1994) and have more alcoholrelated problems (Hill and Muka, 1996; Schuckit, 1982).

Accepted December 7. 1998.

Dr. Kuperman is Associate Professor and Mr. Schlosser and Ms. Lidral are

Research Assistants. Department of"Psychilltry. University of IOWIl College of

Medicine. 10WI' City. Dr. Reich is Research Associate Professor; Department of

Psychiatry. WllShington University School of Medicine. St. Louis.

Reprint requests to Dr. Kuperman, Department of Psychiatry. University of

Iowa Hospitals and Clinics. 200 Hau.kins Drive. RM 1873 JPP. Iowa City. IA

52242-1057.

0890-8567/99/.)806-0686101999 by the American Academy of Child

and Adolescent Psychiatry.

The association of parental alcoholism with the rates

of actual child psychiatric disorders is less clear. Early

studies of COAs found a positive increase in the rate of

attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (AOHO) (Earls

et al., 1988; Goodwin, 1985; Goodwin et al., 1975;

Stewart et al., 1980) and childhood conduct disorder

(CD) or oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) (Earls

et al., 1988; Merikangas et al., 1985; Steinhausen et al.,

1984), but more recent studies have not confirmed these

nndings. Hill and Hruska (1992) examined the rates of

psychopathology in 53 children from families with multigenerational alcoholism and compared them with rates

in 42 children who had no nrst-degree relatives with a

DSM-III diagnosis; the 2 groups did not differ in the

rates of specific DSM-III diagnoses. Reich et al. (1993)

found that the rates of DSM-III diagnoses of ODD,

CD, overanxious disorder (OAO), and marijuana abuse

significantly increased as the number of parents with

alcohol dependence increased from 0 to 2 in a study of

123 children. Finally, Hill and Muka (1996) found that

38 adolescents with multiple family members with alcoholism were more likely to have a psychiatric diagnosis

(but no specific diagnosis) than 38 matched adolescents

686

J. AM. ACAD. CHI!.D A[)O!.ESc:. PSYCHIATRY, '>8:6. JUNE 1999

PSYCHOPATH OL O GY IN C H I LD REN OF ALCOH OLI C S

from families without a history of alcoholism in firstand second-degree relatives.

The differences in published rates of child psychiatric

disorders in COAs have 4 possible explanations. First,

the increased rates of parental separation, decreased family income, and a dysfunctional parenting style (DPS)

(Connolly et aI., 1993) have not been accounted for in

studies of COAs . These factors by them selves are associated with higher rates of child psychopathology (Garm ezy

and Masten, 1994; Patterson et al., 1989; Patterson and

Stouthamer-Loeber, 1984). Second, only a few studies

have examined the possibility that the increased rate of

childhood psychiatric disorders in COAs is due to a

comorbid psychiatric diagnosis in the alcoholic parent

or to psychiatric illness in the nonalcoholic spouse (Hill

er al., 1977; Tubman, 1993). Third, studies have frequently

used restrictive subject groups (e.g., examining children

of parents in treatment for alcoholism , or, conversely,

examining children with specific psychiatric disorders

followed by investigation of their parents for alcoholism) with relatively small sample sizes, limiting the ability to generalize findings (Connolly et al., 1993). Fourth,

studies have used relatively small sample sizes in comparison to the complex issues being explored.

The Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcohol ism (COGA) is a National Institute on Alcohol Abuse

and Alcoholism-funded study that is able to address

these concerns. COGA is composed of 6 sites located at

the State University of New York at Brooklyn, the University of Connecticut at Farmington, Indiana University

in Indianapolis, Washington University in St. Louis, the

University of Iowa in Iowa City, and the Univer sity of

California at San Diego. Data collected for COGA are

wide-ranging and for each participant include fam ily

and demographic information, laboratory tests, and a

semistructured psychiatr ic assessment.

The goal of this study was to use the COGA sample

to assess whether the: risks for specific child psychiatric

diagnoses were increased in COAs , and if so, to determine

whether these increa ses were related to parental diagnoses of alcoholism and antisocial personality disorder

(ASPD) and/or DPS and low socioeconomic status (SES).

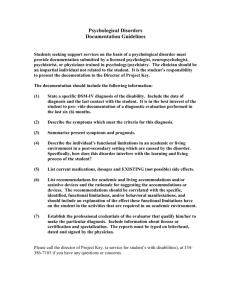

METHOD

A description of the stu dy design and copies of all interview instruments were approved by th e institutional review boards at all 6 sites.

Parents provided info rmed con sent and child ren yo unger th an 18

years of age provided informed assent for parti cipation in th e stu dy.

J. AM. ACAD . CHILD A D O I. ESC. PSYCHIA T RY, .,8:(" JUN E 1999

Subjects

Three quarters of the children in thi s stu dy were from high-risk

COGA families identified through the following criteria. First, an adult

family member had to be in treatment for alcoholism. Second, according to the Semi-Stru ctured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism

(SSAGA) (Bucholz er al., 199 4). th is individual was determi ned to have

both a DSM-lll-R diagn osis of alcoh ol dependence and a Feighner

diagno sis of definite alcoho lism (Feighner et al., 1972) . Third, this

inde x per son gave perm ission to contact all his/her immediate and

extended relatives, includ ing children. for enrollment into th e stu dy.

The remaining children came from low-risk C O G A families whose parents were recruited from dental and fam ily practice clinics, businesses,

churches, and driver's license renewal centers. The parents of these children were also interviewed with the SSAGA.T he presence or absence of

any psychiatric disorder, including alcohol dependence, was not used to

exclude low-risk families.

Indiv iduals in this study yo unger th an the age of 18 were interviewed using the Child Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics

of Alcoholism (C- SSAGA). which closely follows the D iagnostic

Interview for Children and Adolescents (Reich er al., 1982) and

allows the identification of DSM-lll-R diagno ses. Three versio ns of

the C-SSAGA exist: th e C-S SAGA-C for ch ildren aged 7 to 12 years,

the C-SSAG A-A for children aged 13 to 17 years (both versions have

age-app ropr iate wording and examples), and a parent co rroborating

versio n, the C-SSAGA-P.

To be included in th is stu dy a family had to have at least 4 completed sem istructu red interviews; both biological parents had to have

completed SSAGAs, each child had to have co mpleted a C-S SAGA,

and a parent (most likely the biological mother) had to complete a CSSAGA-P for each child . Research assistants who had extens ive training gave all interviews . Furthermore. all inte rviewers part icipated in

monthly conference calls to review subject data and redu ce the likelihood of int erviewer d rift. Different research assistants int erviewed

par ents and children , which minimi zed potential int erviewer bias

du e to a priori knowledge of parent or child symptomato logy.

C hild ren in the sam ple were separated into groups based on the

pr esen ce or absen ce of parental DSM-lll-R diagnoses of alco hol

dependence (alcoholism) and/or ASPO. To more clearly define "alcoholism ," i.e., a DSM-1I1-Rdiagnosis of alcohol dependence, 10 families in which any parent had a DSM-Ill-R diagnosis of alcohol abuse

were dropped from further analysis. Furthermore, becau se of small

numbers, 3 children whose parents had ASPO but no alcohol diagnoses

were also excluded from the analysis. T his resulted in the 3 parent

type (PT) groups: 118 child ren from 67 fam ilies in the "no parental

alcoholism or ASPO " (NPAA ) group, 266 child ren from 165 families

in th e "parental alcoh olism only" (PAO ) group, and 79 child ren from

50 families in the "both parental alcoholism and ASPO " (BPAA)group .

The relationsh ips of 2 different types of variables were examined

across the 3 PT groups. The first consisted of the actual DSM-lll-R

diagnoses of the children and the second consisted of family variables,

which had the possihiliry of influencing these psychiatri c diagnoses.

The diagnoses examined in this study were the disruptive behavior disorders of AOHO, ODD, and CD; the internalizing disorders of OAD

and separation anxiety disorder (SAD) ; and the substance abuse disorders of alcohol abuse and marijuana abuse. (Because of potential difficulties associated with the more episodic diagnosis of major depressive

disorder in children, it was not included in this study.) These diagnoses

were obtained in a mann er sim ilar to that of Bird er al. (1992 ) and

Shaffer et a1. (1996 ); computer algorithm s were used to combine sym ptoms from both the child and parent versions of the C-SSAGA. though

ident ical symptoms reported by both were counted only once.

687

KUPERMAN ET AL.

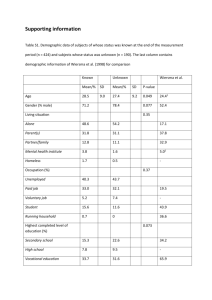

Family variables were divided into 2 clusters. The first cluster, as

shown in Table I, was based on the suggestion by Patterson er al.

(1989) that dysfunctional parenting led to disruptive behavior in

childhood. Twelve C-SSAGA questions were selected as indicators of

OPS for inclusion in this cluster. Four C-SSAGA questions, as shown

in Table I, were selected to form a second cluster based on some of

the risk factors for child psychopathology proposed by Garmezy and

Masten (1994). These consisted of items pertaining to low family

income, failure of parents to complete a high school education, and

marital breakdown and were generally considered to be an indicator

of family SES. A Cronbach a score was calculated on each of the

clusters to determine whether the individual items within the clusters

had sufficient internal consistency to allow the formation of a cluster

sum scale score. Cronbach a scores of .70 for cluster 1 and .60 for

cluster 2 indicated that sufficient internal consistency existed, and

the scores for these 2 clusters were subsequently used in the statistical

models below. Cluster 1 mean ± SO scores for the NPAA, PAO, and

BPAA groups were 1.50 ± 1.8, 2.00 ± 2.1, and 1.80 ± 2.3, respectively. Similarly, cluster 2 mean ± SO scores were 0.14 ± 0.4, 0.80 ±

1.0, and 1.3 ± 1.2 for the respective PT groups.

Statistical Analyses

Because COGA families were collected from 6 different sites, it

was possible that the families differed in a variery of ways (ethniciry,

education, income, etc.), Unequal contribution of families or children

from the different sites would than have the potential of significantly

influencing the data. The distributions of families and children by

site across the 3 different PT groups are shown in Table 2. Preliminary

comparisons indicated no significant differences in the distribution

of families by site across the 3 different PT groups. However, the dis-

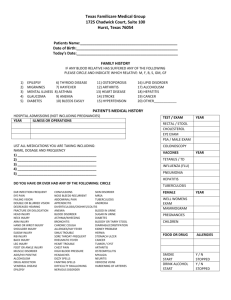

TABLE 1

C-SSAGA Questions That Formed the Basis for Cluster 1

and Cluster 2 Ratings

rriburion of children by site across the 3 PT groups was significantly

different (X 2 = 25.47, df= lO,p < .005).

Another potential complicating factor in analyzing the data was

that on average, each family in the study contributed approximately

2 children to the sample. Generalized estimating equations (GEE)

modeling was therefore performed to analyze the data because the

data for each child had the potential of not being independent from

those for other children in the study. The GEE model nested children

within mothers and adjusted for the fact that data from children in

the same family were correlated while examining the effects of independent variables-a child's gender, age (> 12 years of age), family

rype (whether the children came from high- or low-risk COGA families), placement in PAO group, placement in BPAA group, cluster 1

score, and cluster 2 score---on the dependent variable of a given child

psychiatric diagnosis. Additional independent variables, representing

the effects of recruitment site and recruitment site by PT group interactions, were added to the model based on the uneven distribution of

children across sites. The exchangeable working correlation matrix was

calculated in all cases; exchangeable refers to having a value of 1 on

the diagonal and identical off-diagonal elements corresponding to a

number estimated by default in SAS (Proc GenMod). With binary

data, the "Iogit link" function was used corresponding to logistic

regression. Goodness of fit was assessed using the measures of scaled

deviance and scaled Pearson X2 provided by the procedure. In all

cases the measures were less than I, suggesting a good fit of the model.

The GEE model revealed that of a total possible 35 recruitment

site and 70 recruitment site by PT group interactions, only 2 significant recruitment site effects were noted (each .04 < P < .05). This

occurrence was well below the expected rate of 5 in 100 based on a

probabiliry value of .05. Therefore, the data were reanalyzed with site

and site by PT group interactions eliminated from the GEE model.

RESULTS

Note: C-SSAGA = Child Semi-Structured Assessment for the

Genetics of Alcoholism.

Of the 167 families in the PAO group, a family with

only an alcoholic father was the most common means of

entry into this group (60.9%), followed by families who

had 2 alcoholic parents (21.1 %) and families in which

only the mother had alcoholism (18.0%). Of the 52 families in the BPM group, the distribution of alcoholism

among the parents was similar: only alcoholic fathers

(70.9%), 2 parents with alcoholism (24.0%), and only

alcoholic mothers (5.1 %). The distribution pattern of

parental ASPD in this group was also similar: having only

an ASPD father (91.1 %),2 parents with ASPD (6.4%),

and only an ASPD mother (2.5%).

As shown in Table 3, the percentage of children with

the disruptive diagnoses of ADHD and ODD increased

with parental alcoholism and ASPD. The internalizing

diagnoses of SAD and OAD showed a similar pattern

across the 3 PT groups. Surprisingly, the diagnoses of

alcohol abuse and marijuana abuse showed no pattern to

increasing parental alcoholism or ASPD.

Table 4 presents the odds ratios and significance levels

for the variables in the GEE model by child psychiatric

diagnosis. For the variable gender, an odds ratio greater

688

J. AM. ACAD. CHIl.D ADOl.ESC. PSYCHIATRY. j8:6. JUNE 1999

Cluster 1: Child-Parent Interactions

(Cronbach a = .70)

A.

B.

C.

O.

E.

F.

G.

H.

I.

J.

K.

L.

Your mother and you do not do things together

Your father and you do not do things together

Your mother does not show that she cares about others

Your father does not show that he cares about others

Your mother teases you or hurts your feelings

Your father teases you or hurts your feelings

Your mother frequently criticizes you

Your father frequently criticizes you

Your mother does not compliment you

Your father does not compliment you

You do not feel close to your mother

You do not feel close to your father

Cluster 2: Family Socioeconomic Status

(Cronbach a = .60)

A.

B.

C.

O.

Lives with only 1 biological parent in the household

Family income <$20,OOO/yr

Mother did not complete high school

Father did not complete high school

PSYC H O PAT H OLOG Y I N C H I L D REN OF A LCO HO LICS

TABLE 2

Distribution of the 219 Families" and 463 Children" by Recru itment Site Across the 3 Parent Type Groups

State Uni versity of New York

Families

C hildren

Uni versity of Co nnecticut

Families

C hild ren

Ind iana Un iversity

Families

C hildren

University of Iowa

Fam ilies

C hildren

Washingto n Un iversity

Families

C hildren

University of Ca liforn ia at San Diego

Families

C hild ren

NPAA

(Families n = 67)

(C hildre n n = 118)

PAO

(Families n = 167)

(C hildr en n = 266)

BPAA

(Families n = 52)

(C h ild ren n = 79)

8 (11.9)

21l (23. 7)

20 (12. 1)

34 (12.8)

10 (19.2)

13 (16.5)

13 ( 19.4)

16 ( 13.6)

33 (20 .0)

64 (24 .1)

11 (2 1.2)

17 (21.5)

(7.9)

(6.4)

6 (11.5)

8 (10.1 )

12 (17.9)

22 (18.6)

26 ( 15.8)

37 (13.8)

13 (2 5.0)

2 1 (26.6)

III (26.9)

30 (25.4)

5 1 (30.3)

80 (30 .1)

7 (l3.5)

14 (17.7)

13 (19.4)

III (15.3)

23 (13.9)

34 (l2.8)

3

4

(4.5)

(3.4)

13

17

No te: Values represent n (%) . NPAA = no parent al alcoho lism or antisocial person ality disorder ; PAO

only; BPAA = both parental alcoh olism and anti social personality disorder.

" X 2 = 11.80, df = 10, P = .30.

b Xl = 25.4 7, df = 10, P < .005 .

than 1 indicated that the disorder was more common in

males; for the variable age, an odds ratio greater than 1

indicated that the disorder was more common in children

older than 12 years. An odds ratio greater than 1 for family

type ind icated that the disorder was more common in children from high-risk COGA families. T he odds ratios for

the variables PAO and BPAA indicated the change in relative risk based on whether a child was in 1 of these 2 PT

group s in comparison to placement in the NPAA group .

5

6

(9.6)

(7.6)

= pare ntal alcoho lism

Note: N PAA = no parent al alcoholism or ant isocial personality

disorder; PAO = parent al alcoholism only; BPAA = both parenta l

alcoho lism and antisoc ial person ality disorder; ADHD = artcnrio ndeficit hyperactivity disorder.

Male gende r significantly increased th e odds ratio for

th e follo wing di agn oses: 3.20 times for AOHO (p <

.001) , 3.32 time s for CO (p < .0 1), and 2.17 times for

alcohol abuse (p < .05). Male gender seemed to be protective for th e d iagno sis of OAO, becau se th e risk for

this diagnosis was decreased 0.41 times (p < .05 ). An age

greater 12 years significantly increased the odds ratio for

only 1 diagnosis: 2.24 times for a diagnosi s of CO (p <

.05). The effect of age on th e d iagnoses of alcohol abuse

or mar ijuan a abuse could not be computed because all

children with th ese d iagnoses were older th an 12 years of

age. Family type had no significant effect on any of the

odds ratio s of the ch ild psychiatric diagnoses. In compari son with NPAA ch ild ren, PAO children had an

in creased relati ve risk of 3. 80 times for AOHO (p <

.01) ,6.57 times for CD (p < .001), and 7.79 times for

OAO (p < .001). In comparison with NPAA children,

BPAA children had a significant relative risk of 3.7 1 (p <

.0 1) fo r onl y one d iagnos is: 000. H igh er clu ster 1

scores were associated with a significant relative risk for 3

d iagno ses: 1.37-fold for CO (p < .001), 1.5 5-fold for

alcohol abuse (p < .001 ), and 1.44-fold for marijuana

abuse (p < .00 1). H igher cluster 2 scores showed a relative risk of 1.45 times for CO (p < .05).

J. AM. ACA D. CHIl. D A D O LESC. P SYC H I AT RY. 38:6 . J UN E 19 99

689

TABLE 3

Distributio n in Percent age of C h ildren With DSM -III-R

Di agnoses by Parent Type Gro up

C hild D iagnosis

ADHD

Opposition al defiant d isorder

Conduct diso rder

Separation anxiety disorder

O veranxious d isorde r

Alcoh ol abuse

M arijuana abuse

NPAA

= 11 8)

(n

5.9

5.9

8.5

5.9

2.5

7.6

5. 1

(n

PAO

= 266)

13.2

6.4

14.3

13.9

9.8

5.6

1.9

BPAA

= 79)

(n

19 .0

17 .7

10.1

16 .5

12.7

6.3

5. 1

KUPERMAN ET AL.

TABLE 4

Relative Risks (Odds Ratios) of Children Having a DSM-JlI-R Diagnosis With the Specified Independent Variable

Child Diagnoses

ADHD

Oppositional defiant disorder

Conduct disorder

Separation anxiety disorder

Overanxious disorder

Alcohol abuse

Marijuana abuse

Gender"

Age""

3.20'"

1.62

3.32"

0.41'

0.74

2.17'

2.46

0.74

0.90

2.24'

1.87

0.83

Family

Type"

PAO'

1.98

1.89

1.10

0.42

1.36

0.42

0.66

3.80"

0.41

6.57'''

7.79'"

0.92

0.43

0.30

BPAN

1.78

3.17"

0.46

1.96

1.40

1.14

3.35

Cluster I

Score!

Cluster 2

Score-

1.04

1.07

1.37'"

1.11

1.05

1.55'"

1.44'"

1.17

1.00

1.45'

0.83

1.14

0.99

0.64

Note: Generalized estimating equations modeling; PAO = parental alcoholism only; BPAA = both parental alcoholism and

antisocial personality disorder: ADHD = attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder.

.t An odds ratio> I indicates that the disorder was more common in males.

/, An odds ratio> 1 indicates that the disorder was more common in children older than 12 years.

. All children with alcohol abuse and marijuana abuse were older than 12 years.

d An odds ratio> I indicates that the disorder was more common in children from Collaborative Study on the Genetics of

Alcoholism families.

, An odds ratio> 1 indicates that the disorder was more common in children from the listed parent type group than in children from the "neither alcohol nor antisocial personality disorder" parent type group.

IAn odds ratio> 1 indicates that the disorder was more common in children with higher cluster 1 scores.

g An odds ratio> I indicates that the disorder was more common in children with higher cluster 2 scores.

'p

<

.05;" P < .01; .. , P < .001.

To determine whether cluster scores were directly

related to each other or to either PT group, 2 additional

GEE analyses were performed. These compared a cluster

score, either 1 or 2, with placement in the PAO group,

placement in the BPAA group, and the remaining

cluster score. PT group placement did not affect the relative risk of cluster 1 scores, though higher cluster 2

scores were related to a lA-fold increase in the relative

risk for higher cluster 1 scores (p < .002). PAO group

membership and BPAA group membership increased

the relative risk for higher cluster 2 scores 1.9 and 1.7

times, respectively (p < .004 for both). Higher cluster 1

scores increased the relative risk for higher cluster 2

scores 1.1 times (p < .002).

An indirect measure of the validity of the procedure

for determining child psychiatric diagnoses in this study

can be based on the similar age and gender relationships

of the examined psychiatric disorders compared with other

child psychiatry epidemiological studies: ADHD children

in this study were more likely to be male (Szarrnari, 1992);

children with a diagnosis of ODD were more likely to

be younger boys whereas CD occurred in older males

with more disruptive families (Bauermeister et al., 1994);

and a diagnosis of SAD occurred more often in younger

girls who came from lower SES homes, while OAD was

more common in older girls (Bell-Dolan and Brazeal,

1993). Unfortunately, age and gender data for the specific

diagnoses of alcohol or marijuana abuse were not available. However, comparisons of children in this study with

those in studies of frequent users of these substances, a prerequisite for children who go on to develop a substance

abuse diagnosis, were similar. Substance users were more

likely to be adolescent males (johnston et al., 1995) and

to have parents who were rejecting of their children

(Farrell et al., 1995).

The finding of increased psychopathology in the offspring of alcohol-dependent parents is not unique to

this study (Hill and Hruska, 1992; Hill and Muka, 1996;

Reich et al., 1993), but the relationship of specific diagnoses to parents with only alcoholism and parents with

both alcoholism and ASPD is. Specifically, children from

families with only parent alcoholism had a significant

relative risk for the diagnoses of ADHD, CD, particularly

in boys, and OAD in girls. Surprisingly, BPAA children

had a significant relative risk for only the single diagnosis of ODD though there was a suggestion for the diagnosis of marijuana abuse. A high cluster 1 score did not

seem to be related to parental diagnoses of alcoholism or

ASPD but did seem to be related to a diagnosis of CD.

Unfortunately, the study did not allow direct determination of whether disturbed parenting style was more

690

I. AM

DISCUSSION

ACAIl. CHILIl AIlOLESc:. PSYCHIATRY,

.~H:('.

JLJNE 1999

PSYCHOPATHOLOGY IN CHILDREN OF ALCOHOLICS

likely to lead to a diagnosis of CD or whether a diagnosis of CD was more likely to lead to disturbed parenting.

Unexpectedly, there were 2 "relationships" in this study

that were nonsignificant: the relationship between a

parental diagnosis of alcoholism and a childhood diagnosis of alcohol abuse, and between a parental diagnosis

of ASPD and a childhood diagnosis of CD. The lack of

a significant relationship for both of these may be due to

the relatively young age of the children in this study.

Overall, the average age of 12.1 ± 3.3 years for the children in the study who had an alcoholic parentts) was significantly younger than the averageage of 14.2 ± 3.0 years

for the children whose parents did not have this diagnosis (T= 6.31, df= 223.3,p < .0001). Both of these ages

were well below the late-adolescent to early-adulthood

years more commonly associated with the onset of alcohol abuse or dependence (Goodwin, 1985);(Schuckit,

1982). Additional support for this hypothesis was the

finding that the diagnosis of alcohol abuse was given

only to older children in this study; the average age of

the 29 children with this diagnosis was 16.6 ± 1.0 years.

Therefore, it is possible that as the children with alcoholic parents grow older they will themselves develop

increasing problems with alcoholism. Similarly, the average age of the 79 children with an ASPD parentis) was

12.2 ± 3.2 years, which was somewhat young for a diagnosis of CD. Combining the number of children with

ODD (the possible child precursor of adolescent CD)

with the number of children with CD produced a rate of

27.8% of the children with an ASPD parentfs) (BPAA

children) versus 14.4% in NPAA and 20.7% in PAO

children. These rates were in the direction that suggested

a relationship to parental ASPD.

A strength of this study is that it has improved upon

some of the methodological difficulties found in early

studies. Families were not selected on the basis of direct

parental involvement in alcohol treatment programs or

on the basis of children being followed in psychiatry

clinics; the study is therefore more representative of

alcohol-dependent parents and families in the general

population. Appropriate statistical methods were used to

allow the inclusion of multiple siblings from a given

family so that appropriate inferences could be made on

the contribution of familial data, in addition to that of

parental diagnoses of alcoholism and ASPD, to child

psychopathology. Finally, the sample size was larger than

in previous studies and increased the statistical power of

the analyses.

J. AM. ACAD. CHIl.D ADOl.ESC. PSYCHIATRY, .\8:6, JUNE 1999

However, limitations exist for this study. First, although

there were minimal site differences in the rates of 2 diagnoses, recruitment site differences in rates of psychopathology have been reported in other multisite studies such

as the Epidemiologic Catchment Area and the Depression

Collaborative studies (Coryell et al., 1981; Weissman

et al., 1988). The minimal differences in rates in the current study were felt to be due to chance and not to procedural differences because of standardized instruments and

interviewer training. Second, all comorbid parental diagnoses were not considered. This was an intentional decision because differentiation of children based on multiple

combinations of parental diagnosis would greatly decrease

the number of children in each PT group, thus reducing

statistical power. Third, the study design did not allow

examination of actual genetic transmission of specific

DSM-III-R diagnoses among the COAs. Therefore, findings can be interpreted as only familial in nature, neither

purely genetic nor environmental. Finally, although an

attempt was made to account for the factors of DPS and

family SES, the literature in this area is still incomplete

and the effect of additional individual items or clusters of

symptoms is unknown.

Clinical Implications

Children from families with an alcohol-dependent parent (or parents) were at increased risk for several psychiatric diagnoses includingADHD, CD, and OAD. BPAA

children were at increased risk for the single diagnosis of

ODD, though it is likely they were at increased risk for

the spectrum of child/adolescent equivalents of ASPD,

i.e., ODD in children and CD in adolescents. The risk for

alcohol abuse was not greater in the offspring of these parents, although this likely was the result of the relatively

young age of the examined offspring. Familial and SES

characteristics had an additive effect to parental diagnoses

on the risk of some childhood diagnoses but overall contributed less to this risk than did parental diagnoses.

The observed increased risk for the offspring of alcoholdependent and ASPD parents developing a child psychiatric disorder was familial in nature and included the potential of genetic predisposition as well as the possibility of

other environmental interactions that were not measured

by this study. This finding may lead to the hypothesis that

the etiology of the child psychiatric diagnoses discussed

above may be different from that of those occurring in

children whose parents do not have alcohol dependence or

ASPD or in parents who have the same psychiatric diagno-

691

K UP E RM A N ET A I..

sis as their offspring (e.g., a parent has a diagnosis of

ADHD and his or her child has the same diagnosis).

T he study raises several treatm ent issues: Will th e successful treatment of parental alcoho lism lower the risk

(or recurrent risk) of a psychiatri c disorder in th e offspring? Will the successful treatment of a ch ild with a

psychiatr ic disorder who has a parenrts) with alcoholism

lower that child's risk of develop ing alcoholism as he/ she

approaches the typ ical age of risk? Is the successful treatment of a child with a psychiatri c disorder who has parent s with alcoholism similar to the treatment of a child

with a psychiatric disorder whose parents do not have

alcoholism?The ongoing COGA study has the potential

to provide the opportunity to periodically reexamine the

child ren over time and, in a naturalistic way, to determine the outcome of several of these questions.

Collaboratioe Study 0 11 thr Generics ofAicoho lism: H. Begleiter. SVNY.

Principal tn restigm or. 7: Reich, W,ubillg toll University. Co-Principal

IIll'migator. Th e 6 sitrs an d Principal bll't'stigaton and Co- ln oestigators are

Indiana Uniuersit y (j. Num hugrr. [r., T.-K. Li. PM. Co 11nrally ,

H. Edmhrrg); Uniuersiry of louia (R. Crou'r, S. Kuperman); University of

CitliJom itl Stili Dirgo and Th « Scripps Rrsearch Instit ute (M . Sch ucla t.

r: Bloom ); Uniurrsiry 0/ Connrcticut ( V, Hrssrlbr ock): S VNY H S CH

(H. Brglrita. H. Porjesz): and Wasbillgloll University ill St. Louis ( T. Rricb.

C.R. Clol/illgt'r, j. Rice). This national collaborative sw dy is supported by the

National Institutr 0 11 Alcohol Ab use and Alcoholism (N 1AAA) by U.S.

Public Health Seruic« grtl1JtS N 1AAA U IOAA 0840 1. UIOAA08402. and

V IOAA 08403.

REFERENCES

Bauermeister jJ, Canine C, Bird H (1')') 4) , Epide m iology of disruptive beh avio t d isorders. In: Disruptiue Disorders. Cteen hill LL, ed. Philadelphi a:

Sau nders, PI' 177-1')4

Bell-Dol an D, Brazeal TJ (1') ')3). Separation anxie ty disorder, over an xio us

diso rder, and scho o l refu sal. In : Anxietv Disorders, Leonard H L. cd .

Phi ladelp hi a: Saunders. 1'1' 'i(,j - 'i78

.

Bird H R. Could MS . Sraghczz» B ( 1')')2). Aggrega ti ng d ata from mult iple

in fo rm an rs ill chil d psychiat ry epidem iological resear ch . ] Am Acad Child

Adolrsc Psychiatry 3 1:78-85

Bucholz KK. 'C ,dor~t R. Cloninge r C R er al. (1')') 4 ). A new. semi-str uctu red

psyc hiatric in terview fo r usc in gen et ic lin kage stud ies: a repo n on the

reliabi lity of rhc SSAC;A.] Stud Alcohol 55 : 14')-1 58

C o n no lly CM. Casswell S, Stewart J. Silva PA. O ' Brien M K ( 1')')3). T he

etTen nf parents alco ho l problems o n chil d ren's beh aviour as reported by

parel1ls and by teac hers . Add iction 88 : U83-1390

C o ryell W. Wi no kur C. Andreasen N C (198 1). Ellec t of case de fini t io n o n

alle ctive di so rde r rates. Am] Psvchiatrv U8 : 1106 - 1109

Earls 1'. Reich W. Jung KG , C lon i,;g<'r Cll. ( 1')8 8). Psychopatho logy in child ren of alcoh ol ic an d antisocial parent s. Alcohol Cl i» £\1' R" 12:48 1- 487

692

Farrell M P, Barnes GM , Baner jee S ( I')') S). Family cohesion as a buffe r against

the effec ts of pro blem- d rinki ng fathers o n psych ological di st ress. deviant

behavior. and heavy d rinki ng in ado lescent s. J Health SocBehau36:377-385

Feigh ne r J p, Robins E, G UI.e SB. Woodruff RA. W ino kur G . Mu nos R (1972 ).

D iagnostic criteria fo r use in psychi atri c research . Arch Gen Psychiatry

26 :S7-63

Fergusso n D M , Lynskey MT, Horwood l.J (1994 ). C hi ld hoo d exposu re to

alco ho l and ado lesce nt d rink ing patterns. Addiction 89 : 1007-10 16

Garmezy N , Mas ten AS (199 4) . C h ro nic adve rsities . In: Child and Adolescent

Psychiatry: ModernApproaclm. Rut ter M. Taylo r E. He rsov L. eds. London :

Blackwell Scientific Publicat ions. PI' 191-208

(;oodwi n D W (1985), Alco ho lism and genet ics: the sins of the fathers . Arch

Gm Psychiatry 42 :17 1-174

Good wi n DW , Sch ulsinger F, H ermansen l., G uzc SB. W in oku r G (19 75 ).

Alco ho lism and th e hype rac t ive chil d sy nd ro m e. J Nail Menr Dis

160:349-353

H ill SY, C lo ninger CR, Ayre FR (1977). Ind ependent familial tran sm ission

of alcoholism and opiate abuse. Alcohol Clin F..xp Res 1:335-34 2

Hi ll SY. Hruska DR (1992 ). C hild hood psychopathology in famil ies with

rnulr igenerarional alc o h o lism. JA m Acad Child Adolrsc Psychiat ry

31: 1024 - 1030

Hi ll SY. Muka D (19 96). C hild hood psychopa tho logy in ch ildre n fro m families of alco holic fema le probands. J Am Acad Child Adolrsc Psychiatry

J5 :725-7.B

joh nsron LD , O ' Ma lley PM . Bachman J G (199S) . National Sltrl't'J Result: on

Drug UseFromMonitoring thr filfllrt'SlUdy. 1975-1992. Vol I: Secondary

School St ud ents. Rockvi lle. MD: Narional In st irute o n Drug Abuse

Mcri ka ngas KR. Weissman MM. Pru soff BA. Pauls DL . Leckm an J F (1985).

Depre ssives with secon dar y alco ho lism: psychiat ric disord ers in offspring .

l Slltd Alcohol At»: 199-204

Patterso n G R, Debar yshe BD . Ram sey E (1')89 ). A developmental pe rspec tive on antisocia l beh avior. Am PsychoI 44:.U9-335

Patterson G R. Srourharner-Loeber M (1984). T he co rrela tio n of family ma nage mc nt practi ces and delin q uency. Child De u 55 : 1299-1307

Reich W, Ea rls F. Fra nkel O. Shay ka JJ (1993), Psych o pathol ogy in childr en

of alco ho lie.s.] Am Acad Ch ild Adolesc Psychiatry 32:')95-1002

Reich W. H er jan ic B, Weiner Z . Gandhy pR (198 2) . De velopment of a structured psychiat ric interview for chil d ren: agree ment on d iagnosis co mpa ring child and parent in terviews. J Ab no rm Child P~ychollO : 3 2 5 -.B 6

Roosa M W. Sandler IN. Beals J. Sho rt J L (1988). Risk sta tus o f adolesce nt

children of problem-dr inkin g parents . Am ] Commu nity Psycho/ 16:225-23')

Sch uc kit MA (1982 ). A st ud y of you ng men wi th alcohol ic close relat ives.

Am] Psychiatry 139: 79 1- 794

Shaffer D. Fisher P. Dulcan MK et al. ( 1')96) . The NIMH Diagnosti c int erview Schedule lor Children Version 2.3 (D1SC- 2 .3 ): description. acce ptability. prevalence rates. and perfor man ce in the MECA study.] Am Acad

Child Adolesc Psychiatry 35:865-877

Srcinhauscn He, G obel D . Nestler V ( 1984). Psychopathology in the offspring of alco ho lic pa rents.] Am Acad Child Psychiatry 23:46 5- 471

Stewart MA , DeBl oi s CS . Cu m m ings C (1980) . Psych iatr ic di sord er in the

pa rents o f hyperactive boys and t hose wi th co nd uct di sord er. ] Child

PSY"ho! Psychi,ury 2 1:283 - 292

Szatrnari I' (1992). The epi demiology of attention d eficit hyper act ivity d isor der. In : Attrntion-Deficit Hyperaa iuity Disorder; We is G . cd . Ph iladel ph ia:

Saunders . 1'1' .~ 6 1 -3 84

T ub man J G ( 1993), A pilot stud y of schoo l-age chi ld ren of m en wi th m odcrate to seve re alcoho l depend ence: materna l d istress an d child o ut co mes .

J Child Psycho! Psychiatry 34:729- 741

Weissma n MM , Leaf P] , T ischler G L et al, (1988 ). Affective d isord er s in five

Uni ted Sta tes co m m u nit ies. Psycho! Med /8:141-1 53

West M O . Pri nz RJ ( 1987 ), Pare nt al alcoholis m and ch ild hood psych opat ho logy, Psycho! Bull 102:20 4 -218

J , AM. ACAD. CHIl.D ALJ O l. ESC . PSYC H IAT RY, .18:6, JUN E 199 9