On The Relative Distortions of State Sales and Corporate Income Taxes

advertisement

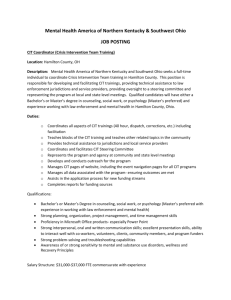

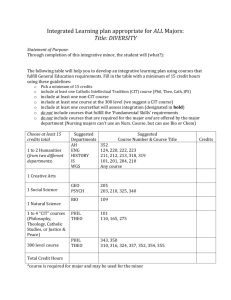

On The Relative Distortions of State Sales and Corporate Income Taxes Donald Bruce Center for Business and Economic Research University of Tennessee (dbruce@utk.edu) John Deskins* Department of Economics and Finance Creighton University (johndeskins@creighton.edu) William Fox Center for Business and Economic Research University of Tennessee (billfox@utk.edu) June 2008 *Corresponding Address: John Deskins, College of Business Administration, Creighton University, 2500 California Plaza, Omaha, NE 68178 1 On The Relative Distortions of State Sales and Corporate Income Taxes Abstract: We use a 1985-2005 panel of state data to investigate the relative tax base elasticities of two major US state taxes—corporate income taxes and sales taxes—with respect to changes in their tax rates. We focus on these two taxes because they are essentially flat-rate taxes at the state level, making it relatively straightforward to construct estimates of their bases using aggregate collections and rate data. Building on recent work on the elasticity of taxable income for the federal personal and corporate income taxes, we estimate several regressions of alternative measures of state tax bases on state tax rates and other controls. We find that both tax bases are responsive to changes in tax rates, and that neither one is universally more elastic than the other. Our estimated elasticities are a bit larger than estimates from recent federal studies, due in large part to taxpayers’ ability to move taxable base across state lines without changing federal taxable income. JEL Codes: H2, H7 2 1. Introduction The efficiency implications of tax policy rest fundamentally on the degree to which government intervention distorts the behavior of firms and individuals. An increasingly common way to quantify the overall distortions of particular tax policies is to examine the responsiveness of the tax base with respect to the tax rate. Most prior studies in this area have examined the responsiveness of taxable income to tax rates, focusing on the federal personal income tax (see Feldstein, 1995, and Gruber and Saez, 2002, for example). Additional research has examined the effects of the federal corporate income tax (Gruber and Rauh, 2005). This approach has the benefit of providing a broad and more general means of capturing the overall welfare consequences of tax policy relative to focusing on a particular aspect of the behavioral effect of taxes, such as labor supply or savings behavior, since examination of the overall tax base change encompasses all behavioral elements. 1 Only a very small number of studies have been identified that examine, wholly or in part, the elasticity of taxable income for state-level taxes (Long, 1999, for example). In this study, we investigate the relative distortions of state sales and corporate income taxes by constructing a series of regression models to estimate the responsiveness of each state tax base to changes in the respective tax rate. We focus on these two taxes because in practice, they typically operate as essentially flat-rate systems at the state level. It is therefore straightforward to calculate accurate approximations of their tax bases by dividing aggregate collections by the tax rate. State individual income taxes, which are a major source of state tax revenue, typically have progressive rate structures and also typically involve tax bases that differ markedly from such available proxies as personal 3 income. Using a panel of state data spanning the years 1985 to 2005, we examine several alternative measures of tax bases in order to provide a broad sense of the robustness and reliability of our results. A better understanding of the relative distortions caused by state sales and corporate income taxes will aid in the design of more efficient tax systems on three dimensions. First, it will provide information to help determine the optimal size of government by providing a better understanding of the deadweight costs of taxation that partially offset the marginal benefits of publicly-provided goods and services. Second, the results will aid in the design of more efficient state tax portfolios in the choice of whether to place a relatively heavier reliance on sales or corporate income taxes to fulfill revenue requirements. Third, when compared with the available results from studies of federal taxes, the results can speak to the debate concerning the optimal allocation of taxing responsibilities of national versus sub-national governments in a federal system by providing information on the relative distortions of taxes at these different levels of government. Analysis of taxable base elasticities at the state level adds several dimensions that have not received significant attention at the national level. First, cross-state tax base mobility can add an important cause of distortions. That is, in addition to all the ways in which taxes may distort behavior when imposed at the national level, they can induce taxpayers to shift potentially taxable bases, either by relocating real economic activity or by engaging in tax planning, between states. The potential for cross-state mobility to affect the elasticity is likely to vary between taxes on sales, individual income and corporate income. An extensive literature has developed on how specific taxes affect 1 Feldstein (1995) makes an effective case for examining the responsiveness of taxable income. 4 business location (see Wasylenko, 1997), but this literature only accounts for part of the overall taxable base elasticity. 2 Further, the measured base responses could depend on a set of tax-specific institutional rules that determine which activity is taxable and where. The specific rules can influence a taxpayer’s ability to engage in tax planning activities, and therefore the taxable base elasticity, without affecting the mobility of real activity. The rules also influence the base breadth, and the elasticity may differ across components of the base. The standard determining nexus is a key aspect affecting the capacity to engage in tax planning. Sales tax nexus requires physical presence. 3 On the other hand, essentially every state uses either a “doing business” or an “earning income” concept to define nexus for the corporate income tax (CIT). The CIT nexus standards generally do not require physical presence for corporations to be taxable, though the issues continue to be litigated. Further, states have been relatively aggressive in seeking to limit corporate tax planning strategies. Some impose combined reporting rules, others assert nexus over passive investment companies without physical presence and others disallow deductions for some types of related companies without physical presence (Fox, Luna and Murray, 2005). Our results indicate that taxable bases respond significantly to tax rates. More specifically, we find that both the sales and the corporate income tax bases are responsive to changes in statutory tax rates, and that neither tax base is universally more elastic than the other. Furthermore, consistent with our expectations, our estimated elasticities for 2 3 The literature is more limited on individual taxes (for example, see Conway and Houtenville, 2001). Quill v. North Dakota, 112 U.S. 298 (1992). 5 state sales and corporate income taxes are slightly larger than corresponding estimates for federal personal and corporate income taxes from the earlier research noted above. 2. Earlier Research on Taxable Income Elasticities Only a small number of studies have been identified that examine the responsiveness of taxable bases to changes in tax rates for state sales, personal income, or corporate income taxes. However, a large body of literature has developed recently on the taxable income elasticity of the federal personal and corporate income taxes, both of which are relevant to the present study. Lindsey (1987) and Feldstein (1995) were among the first to estimate the elasticity of taxable income with respect to marginal tax rates, focusing on the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981 and the Tax Reform Act of 1986, respectively. Calculated elasticities in both studies exceeded -1.0 in absolute value, suggesting that the overall deadweight loss of the personal income tax (PIT) was substantial. More recent studies of the same tax reforms using arguably better data sources and methods found smaller elasticities, centering on a value of -0.7 (Navratil, 1995, and Auten and Carroll, 1999). Studies of data surrounding the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993 by Sammartino and Weiner (1997) and Goolsbee (2000) considered the timing of induced changes in taxable income, revealing large short-term elasticities but smaller mid- or long-term elasticities. As data and methods have improved over time, consensus estimates on the elasticity of taxable income have gradually fallen. Gruber and Saez (2002) examined data from 1979 through 1990 and reported an overall elasticity of taxable income of -0.4 and an elasticity of adjusted gross income (AGI) of -0.2. Saez (2003) noted that the ideal 6 tax change for analyzing behavioral responses is mostly a rate change (with few other rule changes), that affects similar taxpayers differently. His ideal case was the “bracket creep” of the early 1980s, in which tax rates changed even though real income might have remained constant. Using this to identify treatment and control groups, Saez (2003) estimated an elasticity of taxable income of -0.3, with elasticities of AGI and wages revealing that most of the response to tax rate changes involves reporting changes rather than labor supply fluctuations. Kopczuk (2005) placed this body of literature in perspective. Noting that most tax reforms involve base (and other) changes in addition to tax rate changes, he concluded that no permanent or structural elasticity of taxable income exists. The elasticity varies over time as different policies change, and within a period of time for varying types of taxpayers. Additional evidence on the variability of taxable income elasticities has been presented in recent work by Giertz (2006) and Heim (2006). While most of the available literature in this broad area has focused on the federal PIT, some recent research has considered the taxable income elasticity for the federal CIT. Specifically, Gruber and Rauh (2005) use micro-level data to estimate the responsiveness of corporate income to changes in a constructed marginal effective corporate income tax rate, at the federal level. Their primary specification estimates an elasticity of taxable income for the federal CIT of -0.2. Very little research has considered these issues with state-level taxes. Long (1999) is perhaps the earliest exception. He examined changes in taxable income reported on federal personal income tax returns in response to variations in state personal income tax rates using micro-level data from 1991. He estimated a taxable income 7 elasticity ranging from around -0.2 to around -0.4, depending on income level, in response to state marginal tax rate differentials. In another recent state-level study, Bruce, Deskins, and Fox (BDF, 2007) examined the elasticity of taxable income for state corporate income taxes as a function of the CIT rate, holding constant state economic activity and other variables. BDF’s approach focused on how firms respond to tax differentials through tax planning, which does not account for the entire set of potential behavioral responses, but BDF employed a similar methodology to that adopted here. The technique used by BDF isolated location distortions (i.e., the movement of physical economic activity) from tax planning activities, which they consider to be the myriad ways in which businesses shift taxable income across state boundaries (or ensure it is not taxable anywhere) to reduce tax liabilities without moving physical business activity. They found that the corporate income tax base shrinks by around seven percent following a one-percentage-point increase in the CIT rate, abstracting from locational distortions. The total response of taxable income to the tax rate (tax planning distortions plus locational distortions) is expected to be at least as great as the tax planning response found in BDF because of the additional potential for physical economic activity to move between states. BDF did not study state personal income or sales taxes. We are sympathetic to the basic message of Kopczuk (2005), Giertz (2006), and Heim (2006) that the pursuit of a single taxable income (or base) elasticity is perhaps a fruitless exercise. With this in mind, we focus instead on a comparison of relative taxable base elasticities across two major state taxes using aggregate data. This is perhaps a more interesting policy issue at the state level since state governments rely on a 8 broader menu of tax instruments to fund public services. Better information about the relative distortions of these alternative taxes might enable state policy makers to design more efficient tax systems. 3. Empirical Design and Data This study attempts to better understand the distortionary effects of state sales and corporate income taxes from a broad perspective. Our basic approach is to estimate a series of regressions of the tax base on the tax rate, for each tax, to produce an estimate of the elasticity of taxable base and, correspondingly, an understanding of the relative efficiency properties of each tax. Our panel regression models take the following forms: Sales Tax Basei,t = α0 + α1 Sales Tax Ratei,t + α2 Populationi,t + S i + T t + εit, CIT Basei,t = β0 + β1 CIT Ratei,t + β2 Populationi,t + S i + T t + μit, where i and t are state and year indices, the Si terms are state fixed effects, the Tt terms are year fixed effects, and the εit and μit terms represent well-behaved residuals. Our panel of data covers all 50 states for the years 1985 through 2005. Note that population is included as a control variable in each model in order to account for scale issues. We now turn to a detailed description of all regression variables. 4 Tax Bases We begin by describing our measures for the sales and corporate income tax bases. For the sales tax base, our first measure is the actual sales tax base as reported by state revenue departments. Unfortunately, we were only able to acquire a sufficiently 4 Summary statistics are presented in Appendix Table 1 and variable descriptions and source notes are presented in Appendix Table 2. 9 long time series of sales tax base data for a subset of sales-taxing states. 5 Given the limited number of observations on the actual tax base, we rely on the flat-rate nature of most state sales taxes in calculating an alternative measure of the base as sales tax revenues divided by the state general sales tax rate. 6 Of course, this approach may yield some mismeasurement because several states use more than one tax rate. For example, seven states tax food for consumption at home at a preferred rate and others levy higher rates on hotel rooms or selected other transactions. Nonetheless, the correlation coefficient between the state-reported sales tax base and our estimated measure is 0.91 among states with data for both measures, which provides considerable comfort in using the estimated base. We also attempted to gather corporate income tax base data from each state, but had far less success than for the sales tax. 7 Thus we rely exclusively on two estimated CIT base measures. Our first measure is CIT collections divided by the top marginal state CIT rate for those states with a corporate income tax. 8 This approach is more likely to suffer from division bias as well as measurement error for the CIT compared to the sales tax since states depart from flat rates more frequently with the CIT. The consequences are likely to be minor in this context for two reasons: First, the majority of 5 We were able to acquire actual sales tax base data from a) four states for the full period 1985 through 2005, b) 15 states for between six and 14 years, and c) three states for five years or less. Overall, we have 231 observations for actual sales tax bases reported by states. 6 Alaska, Delaware, Montana, New Hampshire, and Oregon have no broad based sales tax and are excluded from the sales tax portion of this study (Federation of Tax Administrators, various years). 7 For the CIT, we were able to acquire actual base data for the full period 1985 through 2005 for only two states; we were able to acquire data for five or more years but less than the entire study period from 8 states, and data for one to four year from three states. Overall, we have 133 observations for actual the CIT base as reported by states. 8 Nevada and Wyoming have no broad business tax. Michigan imposed a single business tax until 2007 (sometimes described as a business activities tax or value added tax). Texas is currently phasing out a franchise tax on earned surplus. South Dakota imposes a corporate income tax on banks. Washington imposes a gross receipts tax termed the business and occupations tax. (Federation of Tax Administrators, 10 states (31 out of 44 that taxed corporate income in 2001) have a single rate. Second, the threshold for the top bracket is relatively low in the 13 states with progressive rate schedules, such that the majority of income falls into the top bracket. Indeed, a simple correlation coefficient between the actual CIT base data that we were able to acquire and our approximated measure is 0.96 among states with data for both measures. 9 As another alternative CIT base measure, we divide federal CIT collections (reported for each state) by the top marginal federal CIT rate. We use this measure purely for comparison purposes, however, because differences between the federal and state CIT structures lead us to strongly prefer base measures that are derived from state data.10 Tax Rates and Other Control Variables For sales tax rates, we use the statutory general sales tax rate in each state.11 We measure the CIT rate as the top statutory marginal CIT rate. The use of the top rate potentially introduces measurement error since not every corporation is taxed at the highest marginal rate. The effect of this will be the familiar attenuation bias: estimated elasticities will be closer to zero than the true values. However, this error is likely to be relatively small for the same reasons stated above. Also, we feel that the statutory top marginal rate is the most appropriate measure since 1) most income is taxed at the top 2004) For the purposes of our analysis, Michigan, Texas, South Dakota, and Washington are treated as if they have no CIT. 9 We estimate a parallel model that modifies our baseline to include the income threshold for the top CIT bracket, since this top bracket threshold is directly correlated with the degree to which the tax base is understated by our estimation method. Results for this alternative model, which can be found in Appendix Table 3, are largely similar to the baseline results. 10 An important distinction is that federal CIT data are generally reported for the state from which the firm files its return rather than the states where economic activity is located. 11 Significant variation exists in statutory CIT and sales tax rates, both between states and within states, during the time frame of this analysis. For each of these taxes, over half of the states changed the rate at least one time from 1985 to 2005. 11 rate, and 2) many firms likely view the top marginal rate as the most important policy signal at the aggregate level. In our baseline models we include only the tax rate and a population control, as described in equations 1 and 2 above. However, we go on to estimate other models that include several additional elements to account for differences in the defined base breadth. For the sales tax, we include in these additional models several dummy variables that denote exemptions of certain categories of purchases from sales taxation. In particular, we include dummy variables that denote the presence of exemptions for a) groceries, b) prescription drugs, c) farm equipment, and d) utilities. We also include four dummy variables to denote when these four items are taxed at reduced rates. Complete data for these exemptions are only available for the period 1994 through 2005. 12 In the more detailed CIT models, we include several elements of the CIT structure that would be incorporated in an effective tax rate calculation. For example, we include the sales factor weight in the state corporate income tax apportionment formula. The apportionment formula uses a state’s share of the corporation’s national property, sales, and payroll to distribute the corporation’s national profits to the state for tax purposes. These three factors are added together using weights that the states have been varying as economic development tools. In general, for given tax rates, locating relatively more payroll and property in a state with a high sales factor weight while selling in other states will reduce tax liability compared with locating the payroll and property in a state with a low sales factor weight and higher weights on property and payroll factors (see Edmiston, 2002). We measure the sales factor weight through the use of three categorical variables that denote a) an equally weighted formula in which the sales factor weight is one-third 12 (our reference category), b) a sales factor weight of 50 to 60 percent, and c) a sales factor weight of greater than 60 percent. States have aggressively increased the weight on the sales factor in the formula to lessen origin-based taxation and increase destination taxation. This may reduce the corporate income tax on many multistate (and presumably more mobile) firms without affecting the tax liability of firms that produce and sell within a single state and therefore do not apportion income. For example, in 1990, 32 of the 44 CIT states applied equal weight to all three factors. By 2004, only 12 states applied equal weight to all factors, while 23 states double-weighted the sales factor (a 50 percent weight), and the remainder applied more than 50 percent weight to sales. 13 A dummy variable is used to control for the presence of a combined reporting requirement to help explain state CIT base fluctuations. Combined reporting could reduce economic activity in a state by driving away firms if such requirements effectively raise the CIT burden by disallowing some tax planning opportunities, but it could also broaden the base by lowering the potential for tax planning. Another dummy variable is also included to identify whether states impose throwback rules, which are intended to raise the CIT base by including in firms’ sales factor those transactions that cannot be or are not taxed in the destination state. Throwback rules can create location distortions by raising the origin component of the CIT. 14 Next we include the top marginal personal income tax (PIT) rate to allow for the possibility of base shifting between the PIT and CIT. For example, a higher PIT rate may 12 Observations for 14 states are missing for 1996. We drop these observations from our analysis. A significant amount of this variation occurred during the time period of this analysis. Indeed, 24 states increased their sales factor weight at least once during this time period. 13 13 entice firms to hold more retained earnings, as opposed to paying higher dividends, thus affecting the CIT base. Also, relative PIT and CIT rates might affect the selected organizational forms of new firms, as firms choose between C-Corp, S-Corp, LLC, partnership and other business structures. Our final CIT base determinant is a dummy denoting whether states permit limited liability companies (LLCs; see Fox and Luna, 2005). The LLC structure can be preferred over the C-corporation structure because LLCs also offer limited liability, but in many cases they are treated as pass-through entities with the income taxed only under the PIT system. 15 Further, LLCs are often exempt from some other corporate taxes, such as the corporate license tax in Louisiana. In addition, single-member LLCs allow for several means of tax planning within broader corporate structures. 16 5. Results and Discussion Sales Tax Results. We begin our discussion of empirical results with the sales tax. Note that tax base and tax rate measures enter our regressions in natural logs to facilitate elasticity interpretations of coefficient estimates. Additionally, our estimates are not directly comparable to earlier elasticity-of-taxable-income estimates, which typically include the net-of-tax price rather than the tax rate itself. To facilitate comparisons to earlier results, we multiply our elasticities by (τ-1)/τ, where τ is the average value of the 14 Combined reporting requirements and throwback rules are very common and visible policies that have been used to offset the effects of tax planning but are not the only tools available to limit tax planning. It is much more difficult to obtain reliable data on other policies for all states over a sufficient period of time. 15 The LLC structure also offers some advantages over S-corporations. For example, there is no limit on the number of members of an LLC whereas an S corporation is limited to 100 shareholders (75 before 2005). 16 See Bruce, Deskins, and Fox (2007) for a full discussion of this issue. 14 particular tax rate used in our analysis. 17 We return to this below. Table 1 presents results for our sales tax regressions. In the first column of the table, we present results from our constructed sales tax base measure. Here we find that state sales tax bases decline by 0.49 percent in response to a one-percent increase in the statutory sales tax rate. Based on this estimate, a state that raises its sales tax rate from 6 percent to 7 percent (an increase of one percentage-point, or 16.7 percent) would experience a sales tax base decline of around 8.8 percent. 18 In the second column of the table, we present results using data for the actual sales tax base as reported by states. As previously stated, there are only 231 observations for this model. Here the decline in the tax base associated with a one-percent increase in the rate falls to 0.239 percent. In the third column, we present results from a third model that utilizes our constructed tax base measure, but only uses those same 231 observations that are used in the model presented in the second column to determine to what degree this difference in the two elasticity estimates presented is due to the different set of observations versus mismeasurement in our constructed base measure. In this model, we estimate an elasticity of -0.328. We take this to indicate that the mismeasurement in our constructed tax base measure, for reasons discussed above, yields an elasticity that is around one-third higher than the true elasticity. Applying this to our original estimate of -0.490 would yield an estimate of the true elasticity of about -0.357. In table 2 we present results from the expanded sales tax model in which we include the various exemption (and partial exemption) dummies, as described above to 17 Prior studies typically regress some form of the the log of the tax base on the log of the net of tax price (one minus the tax rate). Since we regress the log of the base on the log of the tax rate itself, which we view as more appropriate given our use of aggregate data, adjusting our estimated elasticities as described in the text gives us equivalent net-of-tax price elasticities. 15 account for differences in breadth of the base. Here we present results for a model with the inclusion of a) just the grocery and prescription drug exemptions, b) just the farm equipment and utilities exemptions, and c) with all exemptions. We do this as a result of limitations on data availability for the exemption categories. In all of these models, we only use data for the period 1994 through 2005, as previously stated. For the models with farm equipment and utilities exemptions, we lose observations for 14 states due to missing data for 1996. In column four we present results from our baseline model, without any exemptions but for the same estimation sample for comparison purposes. In all of these models we find very similar elasticity estimates for the tax rate, ranging from a low (in absolute value) of -0.332 to a high of -0.348. Further, the elasticity estimate in our baseline model is virtually the same as in the models with the exemption dummies, indicating that the inclusion of the dummies does not significantly change our elasticity estimate. This suggests that base breadth has no effect on the taxable base elasticity. Further, we conclude that the decline in our tax base elasticity estimate from our baseline model in Table 1 to the results in Table 2 is due to the difference in the time period considered in the two models (1985-2005 versus 1994-2005). To investigate the possibility of a changing sales tax base elasticity over time, we present an additional model in which we expand our baseline to include an interaction between the sales tax rate and a time trend (which replaces the year fixed effects in order to facilitate the interaction). 19 Results are presented in Table 3, and indicate that the base 18 Multiplying our baseline sales tax elasticity of -0.490 by (τ-1)/τ, which at our average sales tax rate of 5.03 percent would mean multiplying by 0.8, yields a corresponding net-of-tax price elasticity of -0.392. 19 The timed trend takes on the values 1 through 21 for the years 1985 through 2005, respectively. 16 elasticity has grown (in absolute value) over time. 20 The estimated annual taxable base elasticities are shown graphically in Figure 1. As illustrated, the elasticity grew from just over 0.4 (in absolute value) in 1985 to over 0.5 by 2003, an increase of about one-fourth. Possible explanations for the more elastic sales tax bases include the growth of crossborder sales (especially via electronic commerce) and the general upward trend in state sales tax rates. Corporate Income Tax Results. Table 4 presents baseline results for the corporate income tax. In the first column, where the state CIT base is calculated as state CIT revenues divided by the top CIT rate, we find that a one-percent increase in the top CIT rate is associated with a 0.447-percent drop in the CIT base. This estimated elasticity is larger than the -0.20 estimate in the second column, which uses a base constructed from federal data that are reported for each state. The elasticity estimate derived using state data is very similar to the estimate of -0.48 from Bruce, Deskins, and Fox (2007), which isolated the part of the tax base response that is associated with tax planning activity (and which analyzed data for a smaller number of years). The similar elasticities indicate that essentially all of the behavioral response to changes in the CIT rate are associated with tax planning activity rather than locational distortions. These overall findings are generally consistent with the literature that concludes that tax rates affect the location of businesses, but the quantitative effects are very small (see Wasylenko, 1997). In addition, our estimated CIT base elasticities are at least as large as the taxable income elasticity 20 We also estimated a model with a quadratic specification in which we included a) the time trend, b) the time trend squared, c) the CIT rate multiplied by the time trend, and d) the CIT rate multiplied by the time trend squared. Results from this model were virtually identical to the results presented and are available from the authors upon request. 17 with the federal CIT of -0.2 that was reported in Gruber and Rauh (2005). 21 This is consistent with the earlier hypothesis that state-level responses should be larger than their federal counterparts due to the added dimension of mobility between the states. Turning to the first column of Table 5, we present results for our expanded CIT model in which we include several elements that define the tax base. In this model, the taxable base elasticity is very close to the baseline estimate, indicating that as with the sales tax, base breadth has little influence on the taxable base elasticity since adding these elements in the model does not significantly change the baseline results. Other results indicate that a double weighted sales factor weight used in the corporate income tax apportionment formula increases the tax base, relative to states with an equally weighted formula. Further, results indicate that a weight of more than 60 percent on the sales factor also increases the tax base relative to an equally weighted formula. This is the reverse of the expectation by some that higher weight on the sales factor lowers corporate income taxes. In fact, greater weight on the sales factor changes the distribution of taxes by lowering the liability of firms with relatively more sales than payroll and property, and raising the liability of firms with relatively more payroll and property than sales. This is potentially consistent with higher average tax liabilities. Further, the conclusion can still be supportive of state efforts to seek economic development benefits from greater weight on the sales factor. We discuss the apportionment formula further below. We also find that a higher top marginal PIT rate reduces the CIT base. This runs counter to our expectation that a higher PIT rate may enhance the CIT. State PIT rates have fallen consistently over the past 20 years, and the result may evidence that states 21 Multiplying our baseline corporate income tax elasticity of -0.447 by (τ-1)/τ, which at the average CIT rate of 7.55 percent would mean multiplying by 0.87, gives us a corresponding net-of-tax price elasticity of 18 have been more willing to reduce PIT rates in places where the CIT base has been more stable. In the second column of Table 5 we turn back to a consideration of state CIT apportionment formulas. In particular, we investigate the extent to which the taxable base elasticity depends on the apportionment formula. Thus we include an interaction between the top CIT rate and the dummy variables denoting a double weighted sales factor and a sales factor weight of more than 60 percent. Here we find that the taxable base elasticity is closer to zero for states with double-weighted sales factors. Specifically, when using our state measure of the CIT base, the estimated elasticity is only about -0.349 for those states as compared to -0.595 in other states. This is expected since greater weight on the sales factor reduces the origin component of the base. In our final model, we consider whether the taxable base elasticity for the CIT has changed over time, as was the case with the sales tax above. In Table 6 we present results from an adaptation of our CIT model with the several other base controls to include an interaction between the CIT rate and a time trend. 22 Results indicate that the taxable base elasticity for the CIT has grown (in absolute value) substantially over time. This changing effect is depicted in Figure 1. As illustrated, the CIT taxable base elasticity grew (in absolute value) from around -0.4 in 1985 to nearly double its original value by 2003. Several factors could have contributed to this growing distortionary effect of the CIT rate, including an increased ability to move real economic activity to lower tax jurisdictions as technology has expanded the ability to separate production and about -0.389, still above that found by Gruber and Rauh (2005). 22 As in the corresponding sales tax base model, we replace the year fixed effects with a time trend. Also, as in the sales tax model above, we estimated a model with a quadratic specification, and again, results did not differ substantially from those presented. 19 consumption for both goods and services. Also, opportunities have expanded for using tax planning to move bases to lower-tax (or no-tax) jurisdictions as state and local tax practices at large accounting firms have grown rapidly and new business structures, such as LLCs, have developed. The taxable base elasticity may continue to rise as globalization becomes more of a reality. 6. Conclusions We present a series of state-level panel regressions of the responsiveness of state tax bases to changes in state tax rates. Our analysis, which focuses on state sales and corporate income taxes, builds upon recent research on the elasticity of taxable income with respect to changes in marginal tax rates. That research had its origins in the federal PIT area, followed more recently by work on the federal CIT. Only a few studies have explored these issues using state tax data. Our analysis yields several interesting conclusions. First, state sales and corporate income tax bases appear to be responsive to tax rate changes, with elasticity estimates in the neighborhood of -0.3 to -0.35 for the sales tax and -0.4 to -0.6 for the CIT. As expected, the CIT appears to exhibit relatively higher base elasticities than the sales tax. The elasticities for both taxes are observed to be somewhat higher than those found for the federal PIT and CIT using microdata. Specifically, when we convert our tax rate estimates into net-of-tax price elasticities (as presented in prior studies), we find ranges on the order of -0.24 to -0.28 for the sales tax and -0.35 to -0.52 for the CIT. A second key finding is that both base elasticities have grown between 1985 and 2005, with the CIT base elasticity nearly doubling in size and the sales tax base elasticity 20 growing by about one-quarter. In fact, the two base elasticities were approximately the same in 1985, but have moved apart with the more rapid changes in the CIT. It will be important for future research to explore the possible causes for the growing elasticities of these important state tax bases. A third key finding is that controlling for the breadth of the base using characteristics of state tax rules such as sales tax exemption categories, CIT apportionment formulas, and the like, does not appear to have much impact on the estimated elasticities. In some cases, these policy decisions expand or contract the base but do not alter the degree to which the measured base responds to rate changes. Other policy decisions, such as combined reporting, are intended to reduce tax planning, but do not appear to alter the underlying base elasticity. Still, the dollar base loss from a higher rate will rise with policy choices that expand the base. The extent to which these policies have other (non-base) impacts also deserves further attention. A natural extension of the paper would be, of course, to include an analysis of state personal income tax elasticities as well. This will be difficult, however, given that the progressive nature of most state PIT structures complicates the process of calculating PIT bases for each state. A fruitful approach might be to gather state-specific reported PIT base values, but researchers will still face a difficult choice over which PIT rate to use in empirical analysis. 23 Another possibility would be to replicate prior studies by using microdata but instead focusing on state PIT rates. 23 Collection of state level PIT base data is also complicated since the authors found that most states do not report (and in some cases even aggregate) base data. 21 References Auten, Gerald, and Robert Carroll. 1999. “The Effect of Income Taxes on Household Income.” Review of Economics and Statistics 81(4): 681-693. Borjas, George J. 1980. “The Relationship between Wages and Weekly Hours of Work: The Role of Division Bias.” The Journal of Human Resources 15(3): 409-423. Bruce, Donald, John Deskins, and William F. Fox. 2007. “On the Extent, Growth, and Efficiency Consequences of State Business Tax Planning,” in Taxing Corporate Income in the 21st Century, A. Auerbach, J. Hines, and J. Slemrod, editors, Cambridge University Press. Bruce, Donald, William F. Fox, and M. H. Tuttle. 2006. “Tax Base Elasticities: A Multi-State Analysis of Long-Run and Short-Run Dynamics.” Southern Economic Journal 73(2): 315-341. Conway, Karen Smith, and Andrew J. Houtenville. 2001. “Elderly Migration Flows and State Government Policy – Evidence from the 1990 Census Migration Flows.” National Tax Journal 54 (1): 103-123. Edmiston, Kelly. 2002. “Strategic Apportionment of the State Corporate Income Tax.” National Tax Journal 55 (2): 239-262. Feldstein, Martin. 1995. “The Effect of Marginal Tax Rates on Taxable Income: A Panel Study of the 1986 Tax Reform Act.” The Journal of Political Economy 103 (3): 551-572. Fox, William F., and LeAnn Luna. 2002. “State Corporate Tax Revenue Trends: Causes and Possible Solutions.” National Tax Journal 55 (3): 491-508. Fox, William F., and LeAnn Luna. 2005. “Do Limited Liability Companies Explain Declining State Tax Revenues?” Public Finance Review November: 690-720. Fox, William F., LeAnn Luna, and Matthew N. Murray. 2005. “How Should a Subnational Corporate Income Tax on Multistate Business be Structured?” National Tax Journal 58 (1): 139-59. Giertz, Seth. 2006. “A Sensitivity Analysis and New Estimates of the Elasticity of Taxable Income for the 1980s and 1990s.” Working Paper, Congressional Budget Office. Goolsbee, Austan. 2000. “What Happens When You Tax the Rich? Evidence from Executive Compensation.” Journal of Political Economy 108: 352-378. 22 Gruber, Jonathan, and Joshua Rauh. 2005. “How Elastic is the Corporate Income Tax Base?” Presented at Taxing Corporate Income in the 21st Century, co-sponsored by the Office of Tax Policy Research at the University of Michigan and the Burch Center at the University of California, Berkeley. Gruber, Jonathan, and Emmanuel Saez. 2002. “The Elasticity of Taxable Income: Evidence and Implications.” Journal of Public Economics 84: 1-32. Heim, Bradley. 2006. “The Elasticity of Taxable Income: Evidence from a New Panel of Tax Returns.” Working Paper, Office of Tax Analysis, U.S. Department of the Treasury. Kopczuk, Wojciech. 2005. “Tax Bases, Tax Rates, and the Elasticity of Reported Income.” Journal of Public Economics 89(11-12): 2093-2119. Lindsey, Lawrence. 1987. “Individual Taxpayer Response to Tax Cuts, 1982-1984: With Implications for the Revenue Maximizing Tax Rate.” Journal of Public Economics 33: 173-206. Long, James E. 1999. “The Impact of Marginal Tax Rates on Taxable Income: Evidence from State Income Tax Differentials.” Southern Economic Journal 65(4): 855869. Navratil, J., 1995. Essays on the Impact of Marginal Tax Rate Reductions on the Reporting of Taxable Income on Individual Income Tax Returns. Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University. Saez, Emmanuel. 2003. “The Effect of Marginal Tax Rates on Taxable Income: A Panel Study of Bracket Creep.” Journal of Public Economics 87(5-6): 1231-1258. Sammartino, Frank, and David Weiner. 1997. “Recent Evidence on Taxpayers’ Response to the Rate Increases in the 1990s.” National Tax Journal 50: 683-705. Wasylenko, Michael. 1997. “Taxation and Economic Development: The State of the Economics Literature.” New England Economic Review March/April, 37-42. 23 Table 1: Baseline Regression Results - Sales Tax Variable Ln (Sales Tax Rate) Ln (State Sales Tax Revenues/Sales Tax Rate) -0.490*** Tax Base Measure Ln(State Reported Base) -0.239*** Ln (State Sales Tax Revenues/Sales Tax Rate) -0.328*** (0.054) (0.093) (0.105) Population (millions) 0.024*** 0.010 0.008 (0.007) (0.007) (0.008) 18.507*** 18.423*** 18.716*** (0.099) (0.149) (0.170) 945 0.866 231 0.958 231 0.945 Constant Number of Observations Within R-squared Entries are fixed-effcts panel regression coefficients with standard errors in parentheses. *, **, and *** denote statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels. Regression includes state and year fixed effects. 24 Table 2: Regression Results - Sales Tax, Controlling for Various Exemptions Variable Ln (Sales Tax Rate) Grocery Exemption Partial Grocery Exemption Prescription Drug Exemption Partial Prescription Drug Exemption Farm Equipment Exemption Partial Farm Equipment Exemption Utilities Exemption Partial Utilities Exemption Population (millions) Constant Number of Observations Within R-squared Tax Base Measure Ln (State Sales Tax Revenues/Sales Tax Rate) Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Baseline -0.348*** -0.332*** -0.344*** -0.342*** (0.076) (0.077) (0.077) (0.077) -0.036 - -0.008 - (0.026) - (0.030) - 0.001 - 0.008 - (0.034) - (0.035) - -0.192*** - -0.205*** - (0.036) - (0.040) - ---- - ---- - ---- - ---- - - 0.024 0.007 - - (0.022) (0.022) - - 0.009 0.013 - - (0.015) (0.015) - - 0.046*** 0.043*** - - (0.015) (0.015) - - 0.016 0.014 - - (0.015) (0.014) - 0.007 0.007 0.005 0.008 (0.007) (0.008) (0.007) (0.007) 18.595*** 18.341*** 18.583*** 18.369*** (0.141) (0.138) (0.143) (0.137) 540 0.877 526 0.872 526 0.879 540 0.869 Entries are fixed-effcts panel regression coefficients with standard errors in parentheses. *, **, and *** denote statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels. Regressions include state and year fixed effects. ---- denotes insufficient variation. 25 Table 3: Regression Results - Sales Tax with Time Trend Interaction Variable Ln (Sales Tax Rate) Tax Base Measure Ln (State Sales Tax Revenues/Sales Tax Rate) -0.412*** (0.058) Ln (Sales Tax Rate)*Time Trend -0.006* (0.003) Population (millions) 0.023*** Time Trend 0.058*** Constant 17.382*** (0.007) (0.005) (0.095) Number of Observations Within R-squared 945 0.857 Entries are fixed-effcts panel regression coefficients with standard errors in parentheses. *, **, and *** denote statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels. Regression includes state fixed effects. 26 Table 4: Baseline Regression Results - Corporate Income Tax Variable Ln (Top CIT Rate) Tax Base Measure Ln (State Revenues/CIT Rate) Ln (Federal Base) -0.447*** -0.200** (0.076) (0.080) Population (millions) 0.107*** 0.056*** (0.0175) (0.016) Constant 15.902*** 11.255*** (0.186) (0.198) 924 0.519 924 0.773 Number of Observations Within R-squared Entries are fixed-effcts panel regression coefficients with standard errors in parentheses. *, **, and *** denote statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels. Regressions include state and year fixed effects. All percentages are on a 0-100 scale. 27 Table 5: Regression Results - Corporate Income Tax, Controlling for Other Base-Defining Elements Tax Base Measure Ln (State Revenues/CIT Rate) Model 1 Model 2 -0.530*** -0.595*** Variable Ln (Top CIT Rate) (0.076) (0.081) Sales Factor Appt: Double Weight 0.059** -0.428** (0.029) (0.215) Sales Factor Appt: Greater Than Double Weight 0.203*** 0.316 (0.063) (0.653) - 0.246** Ln(Top CIT Rate)*Double Weight Sales Factor Ln(Top CIT Rate)*Greater Than Double Weight Sales Factor Combined Reporting LLC Throwback Rule - (0.108) - -0.066 - (0.329) 0.032 0.023 (0.046) (0.046) -0.009 -0.013 (0.042) (0.042) -0.052 -0.057 (0.054) (0.055) Ln (Top PIT Rate) -0.038*** -0.035*** (0.008) (0.008) Population (millions) 0.099*** 0.096*** (0.016) (0.016) Constant 16.096*** 16.257*** (0.194) (0.206) 924 0.539 924 0.542 Number of Observations Within R-squared Entries are fixed-effcts panel regression coefficients with standard errors in parentheses. *, **, and *** denote statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels. Regressions include state and year fixed effects. All percentages are on a 0-100 scale. 28 Table 6: Regression Results - Corporate Income Tax with Time Trend Interaction Tax Base Measure Ln (State Revenues/CIT Rate) -0.423*** Variable Ln (Top CIT Rate) (0.093) Ln (Top CIT Rate)*Time Trend -0.018*** (0.006) Sales Factor Appt: Double Weight 0.069** Sales Factor Appt: Greater Than Double Weight 0.194*** (0.032) (0.070) Combined Reporting 0.092* (0.052) LLC 0.188*** (0.035) Throwback Rule -0.082 (0.061) Ln (Top PIT Rate) -0.033*** Population (millions) 0.090*** Time Trend 0.047*** Constant 15.305*** (0.009) (0.017) (0.012) (0.206) Number of Observations Within R-squared 924 0.413 Entries are fixed-effcts panel regression coefficients with standard errors in parentheses. *, **, and *** denote statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels. Regression includes state fixed effects. All percentages are on a 0-100 scale. 29 Figure 1: Taxable Base Elasticity Over Time 0 2005 2003 2001 1999 1997 1995 1993 1991 1989 1987 1985 -0.1 -0.2 Elasticity -0.3 -0.4 CIT Sales -0.5 -0.6 -0.7 -0.8 -0.9 Year 30 Appendix 1: Summary Statistics State CIT Revenues/Top CIT Rate (millions) Federal Base Measure - CIT (millions) State Sales Tax Revenues/Sales Tax Rate (millions) State Reported Sales Tax Base (millions) Top CIT Rate Sales Tax Rate Grocery Exemption* Partial Grocery Exemption* Prescription Drug Exemption* Partial Prescription Drug Exemption* Farm Equipment Exemption* Partial Farm Equipment Exemption* Utilities Exemption* Partial Utilities Exemption* Sales Factor Apportionment: Double Weighted Sales Factor Apportionment: Greater Than Double Weight Combined Reporting Throwback Rule LLC Population (millions) Threshold - Top CIT Bracket Notes: All percentages are on a 0-100 scale. All dollar amounts are expressed as current year dollars. *Entries in 1985 column are for 1994. 31 Mean 4,124 32,145 33,100 62,400 7.39 4.56 0.56 0.04 0.96 0.02 0.24 0.22 0.20 0.18 0.14 0.02 0.20 0.56 0 4.75 225,000 1985 Std.Dev. 4,115 48,674 35,800 42,200 2.25 1.07 0.50 0.21 0.21 0.15 0.43 0.42 0.40 0.39 0.35 0.15 0.41 0.50 0 5.07 483,094 Mean 7,708 106,320 75,900 85,600 7.63 5.24 0.60 0.07 0.98 0.02 0.13 0.22 0.20 0.25 0.57 0.16 0.32 0.55 1 5.80 192,857 2005 Std.Dev. 12,600 133,574 76,800 89,800 1.63 1.00 0.50 0.25 0.15 0.15 0.34 0.42 0.40 0.44 0.5 0.37 0.47 0.50 0 6.45 249,227 Appendix 2: Data Descriptions and Source Notes Variable State CIT Revenues/Top CIT Rate Federal Base Measure - CIT State Sales Tax Revenues/ Sales Tax Rate State Reported Sales Tax Base Top CIT Rate Sales Tax Rate Grocery Exemption Partial Grocery Exemption Prescription Drug Exemption Partial Prescription Drug Exemption Farm Equipment Exemption Partial Farm Equipment Exemption Utilities Exemption Partial Utilities Exemption Sales Factor Apportionment: Double Weighted Sales Factor Apportionment: Greater Than Double Weight Combined Reporting Throwback Rule LLC Population (millions) Threshold - Top CIT Bracket Definition Corporate income tax (CIT) revenues divided by top marginal CIT rate. (1) Federal CIT collections divided by top marginal federal CIT rate.(2) Sales tax revenues divided by sales tax rate. (1) State reported sales tax base. (3) Highest marginal corporate income tax rate. (4) General sales tax rate. (4) 1 if a state exempts groceries from sales taxation. (4) 1 if a state taxes groceries at a reduced sales tax rate. (4) 1 if a state exempts prescription drugs from sales taxation. (4) 1 if a state taxes prescription drugs at a reduced sales tax rate. (4) 1 if a state exempts farm equipment from sales taxation. (4) 1 if a state taxes farm equipment at a reduced sales tax rate. (4) 1 if a state exempts utilities from sales taxation. (4) 1 if a state taxes utilitiess at a reduced sales tax rate. (4) 1 if sales factor weight in CIT appt formula is between 34 and 60 percent. (4) 1 if sales factor weight in CIT appt formula is greater than 60 percent. (4) 1 if a state has a combined reporting requirement. (5) 1 if a state has a throwback rule. (5) 1 if a state allows LLCs. (6) State population. (8) Minimum income level for top CIT rate. (4) Source Notes: 1. Authors' calculations based on data from State Government Finances , U.S. Census Bureau, various years, and State Tax Handbook , Commerce Clearing House, various years. 2. Authors' calculations based on data from Statistics of Income, Tax Statistics , Internal Revenue Service, various years, and Federal Tax Guide , Commerce Clearing House, various years. 3. Reported by state revenue departments. 5. State Tax Handbook , Commerce Clearing House, various years. 6. State Tax Handbook , Commerce Clearing House (various years) and various state revenue departments. 7. www.llcweb.com 8. Statistical Abstract of the United States , U.S. Census Bureau, various years. 32 Appendix 3: Corporate Income Tax Robustness Checks Tax Base Measure Ln (State Revenues/CIT Rate) -0.530*** Variable Ln (Top CIT Rate) (0.076) Threshold - Top CIT Bracket (thousands) Sales Factor Appt: Double Weight -0.0001 0.059** Sales Factor Appt: Greater Than Double Weight 0.203*** (0.002) (0.029) (0.063) Combined Reporting 0.032 (0.046) LLC -0.009 Throwback Rule -0.052 (0.042) (0.055) Ln (Top PIT Rate) -0.038*** (0.008) Population (thousands) 0.099*** Constant 16.101*** (0.016) (0.194) Number of Observations Within R-squared 924 0.539 Entries are fixed-effcts panel regression coefficients with standard errors in parentheses. *, **, and *** denote statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels. Regression includes state and year fixed effects. All percentages are on a 0-100 scale. 33