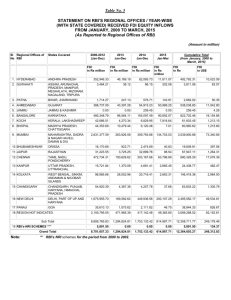

OECD GLOBAL FORUM ON INTERNATIONAL INVESTMENT DIRECT INVESTMENT IN THE 21

advertisement