Market

advertisement

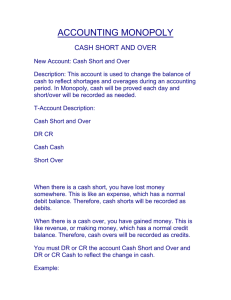

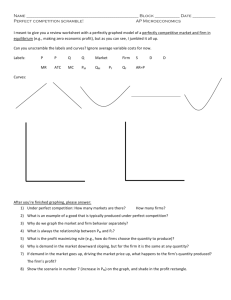

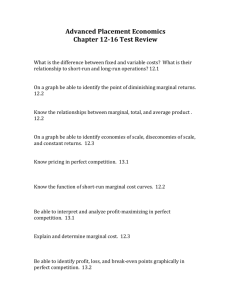

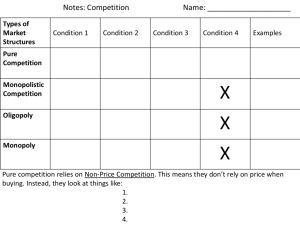

Market In an economic sense, a market is a system by which buyers and sellers bargain for the price of a product, settle the price and transact their business—buy and sell a product. Personal contact between the buyers and sellers is not necessary. In some cases, e.g., forward sale and purchase, even immediate transfer of ownership of goods is not necessary. Market does not necessarily mean a place. The market for a commodity may be local, regional, national or international. What makes a market is a set of buyers, a set of sellers and a commodity. While buyers are willing to buy and sellers are willing to sell, and there is a price for the commodity. The Four Types of Market Structure Number of Firms? Many firms Type of Products? One firm Monopoly • Tap water • Cable TV Few firms Oligopoly • Tennis balls • Crude oil Differentiated products Monopolistic Competition • Novels • Movies Identical products Perfect Competition • Wheat • Milk Copyright © 2004 South-Western Market Structure • Market structure – identifies how a market is made up in terms of: – – – – – – The number of firms in the industry The nature of the product produced The degree of monopoly power each firm has The degree to which the firm can influence price Profit levels Firms’ behaviour – pricing strategies, non-price competition, output levels – The extent of barriers to entry – The impact on efficiency Market Structure Perfect Competition Pure Monopoly More competitive (fewer imperfections) Market Structure Perfect Competition Pure Monopoly Less competitive (greater degree of imperfection) Market Structure Pure Monopoly Perfect Competition Monopolistic Competition Oligopoly Duopoly Monopoly The further right on the scale, the greater the degree of monopoly power exercised by the firm. GAME THEORY AND THE ECONOMICS OF COOPERATION • Game theory is the study of how people behave in strategic situations. • Strategic decisions are those in which each person, in deciding what actions to take, must consider how others might respond to that action. GAME THEORY AND THE ECONOMICS OF COOPERATION • Because the number of firms in an oligopolistic market is small, each firm must act strategically. • Each firm knows that its profit depends not only on how much it produces but also on how much the other firms produce. The Prisoners’ Dilemma • The prisoners’ dilemma provides insight into the difficulty in maintaining cooperation. • Often people (firms) fail to cooperate with one another even when cooperation would make them better off. The Prisoners’ Dilemma • The prisoners’ dilemma is a particular “game” between two captured prisoners that illustrates why cooperation is difficult to maintain even when it is mutually beneficial. Figure 2 The Prisoners’ Dilemma Bonnie’ s Decision Confess Bonnie gets 8 years Remain Silent Bonnie gets 20 years Confess Clyde gets 8 years Clyde’s Decision Bonnie goes free Clyde goes free Bonnie gets 1 year Remain Silent Clyde gets 20 years Clyde gets 1 year Copyright©2003 Southwestern/Thomson Learning The Prisoners’ Dilemma • The dominant strategy is the best strategy for a player to follow regardless of the strategies chosen by the other players. The Prisoners’ Dilemma • Cooperation is difficult to maintain, because cooperation is not in the best interest of the individual player. Figure 3 An Oligopoly Game Iraq’s Decision High Production Iraq gets $40 billion Low Production Iraq gets $30 billion High Production Iran’s Decision Iran gets $40 billion Iraq gets $60 billion Iran gets $60 billion Iraq gets $50 billion Low Production Iran gets $30 billion Iran gets $50 billion Copyright©2003 Southwestern/Thomson Learning Oligopolies as a Prisoners’ Dilemma • Self-interest makes it difficult for the oligopoly to maintain a cooperative outcome with low production, high prices, and monopoly profits. Figure 4 An Arms-Race Game Decision of the United States (U.S.) Arm Disarm U.S. at risk U.S. at risk and weak Arm Decision of the Soviet Union (USSR) USSR at risk USSR safe and powerful U.S. safe and powerful U.S. safe Disarm USSR at risk and weak USSR safe Copyright©2003 Southwestern/Thomson Learning Figure 5 An Advertising Game Marlboro’ s Decision Advertise Marlboro gets $3 billion profit Don’t Advertise Marlboro gets $2 billion profit Advertise Camel’s Decision Don’t Advertise Camel gets $3 billion profit Marlboro gets $5 billion profit Camel gets $2 billion profit Camel gets $5 billion profit Marlboro gets $4 billion profit Camel gets $4 billion profit Copyright©2003 Southwestern/Thomson Learning Figure 6 A Common-Resource Game Exxon’s Decision Drill Two Wells Drill Two Wells Exxon gets $4 million profit Texaco gets $4 million profit Texaco’s Decision Exxon gets $6 million profit Drill One Well Texaco gets $3 million profit Drill One Well Exxon gets $3 million profit Texaco gets $6 million profit Exxon gets $5 million profit Texaco gets $5 million profit Copyright©2003 Southwestern/Thomson Learning Why People Sometimes Cooperate • Firms that care about future profits will cooperate in repeated games rather than cheating in a single game to achieve a onetime gain. Figure 7 Jack and Jill Oligopoly Game Jack’s Decision Sell 40 Gallons Jack gets $1,600 profit Sell 40 Gallons Jill’s Decision Sell 30 Gallons Sell 30 Gallons Jill gets $1,600 profit Jack gets $1,500 profit Jill gets $2,000 profit Jack gets $2,000 profit Jill gets $1,500 profit Jack gets $1,800 profit Jill gets $1,800 profit Copyright©2003 Southwestern/Thomson Learning PUBLIC POLICY TOWARD OLIGOPOLIES • Cooperation among oligopolists is undesirable from the standpoint of society as a whole because it leads to production that is too low and prices that are too high. Restraint of Trade and the Antitrust Laws • Antitrust laws make it illegal to restrain trade or attempt to monopolize a market. – Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 – Clayton Act of 1914 Controversies over Antitrust Policy • Antitrust policies sometimes may not allow business practices that have potentially positive effects: – Resale price maintenance – Predatory pricing – Tying Controversies over Antitrust Policy • Resale Price Maintenance (or fair trade) – occurs when suppliers (like wholesalers) require retailers to charge a specific amount • Predatory Pricing – occurs when a large firm begins to cut the price of its product(s) with the intent of driving its competitor(s) out of the market • Tying – when a firm offers two (or more) of its products together at a single price, rather than separately Summary • Oligopolists maximize their total profits by forming a cartel and acting like a monopolist. • If oligopolists make decisions about production levels individually, the result is a greater quantity and a lower price than under the monopoly outcome. Summary • The prisoners’ dilemma shows that selfinterest can prevent people from maintaining cooperation, even when cooperation is in their mutual self-interest. • The logic of the prisoners’ dilemma applies in many situations, including oligopolies. Summary • Policymakers use the antitrust laws to prevent oligopolies from engaging in behavior that reduces competition. Market Structure • Monopoly: – High barriers to entry – Firm controls price OR output/supply – Abnormal profits in long run – Possibility of price discrimination – Consumer choice limited – Prices in excess of MC • While a competitive firm is a price taker, a monopoly firm is a price maker. • A firm is considered a monopoly if . . . – it is the sole seller of its product. – its product does not have close substitutes. WHY MONOPOLIES ARISE • The fundamental cause of monopoly is barriers to entry. WHY MONOPOLIES ARISE • Barriers to entry have three sources: – Ownership of a key resource. – The government gives a single firm the exclusive right to produce some good. – Costs of production make a single producer more efficient than a large number of producers. Monopoly Resources • Although exclusive ownership of a key resource is a potential source of monopoly, in practice monopolies rarely arise for this reason. Government-Created Monopolies • Governments may restrict entry by giving a single firm the exclusive right to sell a particular good in certain markets. Government-Created Monopolies • Patent and copyright laws are two important examples of how government creates a monopoly to serve the public interest. Natural Monopolies • An industry is a natural monopoly when a single firm can supply a good or service to an entire market at a smaller cost than could two or more firms. Natural Monopolies • A natural monopoly arises when there are economies of scale over the relevant range of output. Figure 1 Economies of Scale as a Cause of Monopoly Cost Average total cost 0 Quantity of Output Copyright © 2004 South-Western HOW MONOPOLIES MAKE PRODUCTION AND PRICING DECISIONS • Monopoly versus Competition – Monopoly • • • • Is the sole producer Faces a downward-sloping demand curve Is a price maker Reduces price to increase sales – Competitive Firm • • • • Is one of many producers Faces a horizontal demand curve Is a price taker Sells as much or as little at same price Figure 2 Demand Curves for Competitive and Monopoly Firms (a) A Competitive Firm’s Demand Curve Price (b) A Monopolist’s Demand Curve Price Demand Demand 0 Quantity of Output 0 Quantity of Output Copyright © 2004 South-Western A Monopoly’s Revenue • A Monopoly’s Marginal Revenue – A monopolist’s marginal revenue is always less than the price of its good. • The demand curve is downward sloping. • When a monopoly drops the price to sell one more unit, the revenue received from previously sold units also decreases. A Monopoly’s Revenue • A Monopoly’s Marginal Revenue – When a monopoly increases the amount it sells, it has two effects on total revenue (P Q). • The output effect—more output is sold, so Q is higher. • The price effect—price falls, so P is lower. Figure 3 Demand and Marginal-Revenue Curves for a Monopoly Price $11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 –1 –2 –3 –4 Demand (average revenue) Marginal revenue 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Quantity of Water Copyright © 2004 South-Western Profit Maximization • A monopoly maximizes profit by producing the quantity at which marginal revenue equals marginal cost. • It then uses the demand curve to find the price that will induce consumers to buy that quantity. Figure 4 Profit Maximization for a Monopoly Costs and Revenue 2. . . . and then the demand curve shows the price consistent with this quantity. B Monopoly price 1. The intersection of the marginal-revenue curve and the marginal-cost curve determines the profit-maximizing quantity . . . Average total cost A Demand Marginal cost Marginal revenue 0 Q QMAX Q Quantity Copyright © 2004 South-Western Profit Maximization • Comparing Monopoly and Competition – For a competitive firm, price equals marginal cost. P = MR = MC – For a monopoly firm, price exceeds marginal cost. P > MR = MC A Monopoly’s Profit • Profit equals total revenue minus total costs. – Profit = TR - TC – Profit = (TR/Q - TC/Q) Q – Profit = (P - ATC) Q Figure 5 The Monopolist’s Profit Costs and Revenue Marginal cost Monopoly E price B Monopoly profit Average total D cost Average total cost C Demand Marginal revenue 0 QMAX Quantity Copyright © 2004 South-Western A Monopolist’s Profit • The monopolist will receive economic profits as long as price is greater than average total cost. Figure 6 The Market for Drugs Costs and Revenue Price during patent life Price after patent expires Marginal cost Marginal revenue 0 Monopoly quantity Competitive quantity Demand Quantity Copyright © 2004 South-Western THE WELFARE COST OF MONOPOLY • In contrast to a competitive firm, the monopoly charges a price above the marginal cost. • From the standpoint of consumers, this high price makes monopoly undesirable. • However, from the standpoint of the owners of the firm, the high price makes monopoly very desirable. Figure 7 The Efficient Level of Output Price Marginal cost Value to buyers Cost to monopolist Value to buyers Cost to monopolist Demand (value to buyers) Quantity 0 Value to buyers is greater than cost to seller. Value to buyers is less than cost to seller. Efficient quantity Copyright © 2004 South-Western The Deadweight Loss • Because a monopoly sets its price above marginal cost, it places a wedge between the consumer’s willingness to pay and the producer’s cost. – This wedge causes the quantity sold to fall short of the social optimum. Figure 8 The Inefficiency of Monopoly Price Deadweight loss Marginal cost Monopoly price Marginal revenue 0 Monopoly Efficient quantity quantity Demand Quantity Copyright © 2004 South-Western The Deadweight Loss • The Inefficiency of Monopoly – The monopolist produces less than the socially efficient quantity of output. The Deadweight Loss • The deadweight loss caused by a monopoly is similar to the deadweight loss caused by a tax. • The difference between the two cases is that the government gets the revenue from a tax, whereas a private firm gets the monopoly profit. PUBLIC POLICY TOWARD MONOPOLIES • Government responds to the problem of monopoly in one of four ways. – Making monopolized industries more competitive. – Regulating the behavior of monopolies. – Turning some private monopolies into public enterprises. – Doing nothing at all. Increasing Competition with Antitrust Laws • Antitrust laws are a collection of statutes aimed at curbing monopoly power. • Antitrust laws give government various ways to promote competition. – They allow government to prevent mergers. – They allow government to break up companies. – They prevent companies from performing activities that make markets less competitive. Increasing Competition with Antitrust Laws • Two Important Antitrust Laws – Sherman Antitrust Act (1890) • Reduced the market power of the large and powerful “trusts” of that time period. – Clayton Act (1914) • Strengthened the government’s powers and authorized private lawsuits. Regulation • Government may regulate the prices that the monopoly charges. – The allocation of resources will be efficient if price is set to equal marginal cost. Figure 9 Marginal-Cost Pricing for a Natural Monopoly Price Average total cost Regulated price Loss Average total cost Marginal cost Demand 0 Quantity Copyright © 2004 South-Western Regulation • In practice, regulators will allow monopolists to keep some of the benefits from lower costs in the form of higher profit, a practice that requires some departure from marginal-cost pricing. Public Ownership • Rather than regulating a natural monopoly that is run by a private firm, the government can run the monopoly itself (e.g. in the United States, the government runs the Postal Service). Doing Nothing • Government can do nothing at all if the market failure is deemed small compared to the imperfections of public policies. PRICE DISCRIMINATION • Price discrimination is the business practice of selling the same good at different prices to different customers, even though the costs for producing for the two customers are the same. PRICE DISCRIMINATION • Price discrimination is not possible when a good is sold in a competitive market since there are many firms all selling at the market price. In order to price discriminate, the firm must have some market power. • Perfect Price Discrimination – Perfect price discrimination refers to the situation when the monopolist knows exactly the willingness to pay of each customer and can charge each customer a different price. PRICE DISCRIMINATION • Two important effects of price discrimination: – It can increase the monopolist’s profits. – It can reduce deadweight loss. Figure 10 Welfare with and without Price Discrimination (a) Monopolist with Single Price Price Consumer surplus Deadweight loss Monopoly price Profit Marginal cost Marginal revenue 0 Quantity sold Demand Quantity Copyright © 2004 South-Western Figure 10 Welfare with and without Price Discrimination (b) Monopolist with Perfect Price Discrimination Price Profit Marginal cost Demand 0 Quantity sold Quantity Copyright © 2004 South-Western PRICE DISCRIMINATION • Examples of Price Discrimination – Movie tickets – Airline prices – Discount coupons – Financial aid – Quantity discounts CONCLUSION: THE PREVALENCE OF MONOPOLY • How prevalent are the problems of monopolies? – Monopolies are common. – Most firms have some control over their prices because of differentiated products. – Firms with substantial monopoly power are rare. – Few goods are truly unique. Summary • A monopoly is a firm that is the sole seller in its market. • It faces a downward-sloping demand curve for its product. • A monopoly’s marginal revenue is always below the price of its good. Summary • Like a competitive firm, a monopoly maximizes profit by producing the quantity at which marginal cost and marginal revenue are equal. • Unlike a competitive firm, its price exceeds its marginal revenue, so its price exceeds marginal cost. Summary • A monopolist’s profit-maximizing level of output is below the level that maximizes the sum of consumer and producer surplus. • A monopoly causes deadweight losses similar to the deadweight losses caused by taxes. Summary • Policymakers can respond to the inefficiencies of monopoly behavior with antitrust laws, regulation of prices, or by turning the monopoly into a government-run enterprise. • If the market failure is deemed small, policymakers may decide to do nothing at all. Summary • Monopolists can raise their profits by charging different prices to different buyers based on their willingness to pay. • Price discrimination can raise economic welfare and lessen deadweight losses. Market Structure • Advantages and disadvantages of monopoly: • Advantages: – – – – May be appropriate if natural monopoly Encourages R&D Encourages innovation Development of some products not likely without some guarantee of monopoly in production – Economies of scale can be gained – consumer may benefit Market Structure • Disadvantages: – Exploitation of consumer – higher prices – Potential for supply to be limited - less choice – Potential for inefficiency – X-inefficiency – complacency controls on costs over Market Structure Price Kinked Demand Curve £5 Kinked D Curve D = elastic D = Inelastic 100 Quantity Monopolistic or Imperfect Competition • In each case there are many firms in the industry • Each can try to differentiate its product in some way • Entry and exit to the industry is relatively free • Consumers and producers do not have perfect knowledge of the market – the market may indeed be relatively localised. Can you imagine trying to search out the details, prices, reliability, quality of service, etc for every plumber in the UK in the event of an emergency?? Oligopoly • Competition between the few – May be a large number of firms in the industry but the industry is dominated by a small number of very large producers • Concentration Ratio – the proportion of total market sales (share) held by the top 3,4,5, etc firms: – A 4 firm concentration ratio of 75% means the top 4 firms account for 75% of all the sales in the industry Oligopoly • Example: • Music sales – The music industry has a 5-firm concentration ratio of 75%. Independents make up 25% of the market but there could be many thousands of firms that make up this ‘independents’ group. An oligopolistic market structure therefore may have many firms in the industry but it is dominated by a few large sellers. Market Share of the Music Industry 2002. Source IFPI: http://www.ifpi.org/site-content/press/20030909.html Oligopoly • Features of an oligopolistic market structure: – Price may be relatively stable across the industry – kinked demand curve? – Potential for collusion – Behaviour of firms affected by what they believe their rivals might do – interdependence of firms – Goods could be homogenous or highly differentiated – Branding and brand loyalty may be a potent source of competitive advantage – Non-price competition may be prevalent – Game theory can be used to explain some behaviour – AC curve may be saucer shaped – minimum efficient scale could occur over large range of output – High barriers to entry Oligopoly Price The kinked demand curve - an explanation for price stability? The Assume If The thefirm principle firmthe therefore, seeks firm ofto is the lower effectively charging kinked its price demand a faces price to of £5‘kinked gain a and a curve competitive producing demand rests on an curve’ advantage, the output principle forcing of 100. itsit rivals to will follow maintain that: asuit. stable Anyorgains rigid pricing it makes will If it chose to raise price above £5, its quickly beOligopolistic structure. lost and the firms % change may in rivals a. would If a firm not raises followitssuit price, andits the firm demand will overcome this beby smaller engaging thaninthe non% effectively rivalsfaces will not an follow elasticsuit demand reduction price competition. in price – total revenue curve for its product (consumers would would b. Ifagain a firm fall lowers as theitsfirm price, nowitsfaces buy from the cheaper rivals). The % a relatively rivalsinelastic will all dodemand the same curve. change in demand would be greater than the % change in price and TR would fall. £5 Total Revenue B Total Revenue A Kinked D Curve Total Revenue B D = elastic D = Inelastic 100 Quantity Duopoly • Market structure where the industry is dominated by two large producers – Collusion may be a possible feature – Price leadership by the larger of the two firms may exist – the smaller firm follows the price lead of the larger one – Highly interdependent – High barriers to entry – Cournot Model – French economist – analysed duopoly – suggested long run equilibrium would see equal market share and normal profit made – In reality, local duopolies may exist Monopoly • Pure monopoly – where only one producer exists in the industry • In reality, rarely exists – always some form of substitute available! • Monopoly exists, therefore, where one firm dominates the market • Firms may be investigated for examples of monopoly power when market share exceeds 25% • Use term ‘monopoly power’ with care! Monopoly • Monopoly power – refers to cases where firms influence the market in some way through their behaviour – determined by the degree of concentration in the industry – – – – – Influencing prices Influencing output Erecting barriers to entry Pricing strategies to prevent or stifle competition May not pursue profit maximisation – encourages unwanted entrants to the market – Sometimes seen as a case of market failure Monopoly • Origins of monopoly: – Through growth of the firm – Through amalgamation, merger or takeover – Through acquiring patent or license – Through legal means – Royal charter, nationalisation, wholly owned plc Monopoly • Summary of characteristics of firms exercising monopoly power: – Price – could be deemed too high, may be set to destroy competition (destroyer or predatory pricing), price discrimination possible. – Efficiency – could be inefficient due to lack of competition (X- inefficiency) or… • could be higher due to availability of high profits Monopoly • Innovation - could be high because of the promise of high profits, Possibly encourages high investment in research and development (R&D) • Collusion – possible to maintain monopoly power of key firms in industry • High levels of branding, advertising and non-price competition Monopoly • Problems with models – a reminder: – Often difficult to distinguish between a monopoly and an oligopoly – both may exhibit behaviour that reflects monopoly power – Monopolies and oligopolies do not necessarily aim for traditional assumption of profit maximisation – Degree of contestability of the market may influence behaviour – Monopolies not always ‘bad’ – may be desirable in some cases but may need strong regulation – Monopolies do not have to be big – could exist locally Monopoly Costs / Revenue MC £7.00 AC Monopoly Profit This(D) AR Given isthe both curve barriers the forshort a to monopolist entry, run and likely the long monopolist run to be equilibrium relatively will be position price able to inelastic. exploit for a monopoly abnormal Output assumed profits in the to be atrun long profit as maximising entry to the output (note caution market is restricted. here – not all monopolists may aim for profit maximisation!) £3.00 MR Q1 AR Output / Sales Monopoly Welfare implications of monopolies Costs / Revenue MC £7 AC Loss of consumer surplus £3 AR MR Q2 A look back at the for The The higher price monopoly in price a competitive price anddiagram lower would be perfect competition will reveal output market £7 permeans unit would with that beoutput £3 consumer with levels that inat equilibrium, price will by be surplus output lower is levels Q2. reduced, at Q1.indicated equal to the MC of production. the grey shaded area. On the face of it, consumers We lookprices therefore a facecan higher and at less comparison of the differences choice in monopoly conditions between and competitive output in a comparedprice to more competitive situation compared environments. to a monopoly. Q1 Output / Sales Monopoly Welfare implications of monopolies Costs / Revenue MC £7 AC Gain in producer surplus The monopolist will benefit be affected from additional by a loss producer of producer surplus equal showntobythe thegrey grey triangle rectangle. shaded but…….. £3 AR MR Q2 Q1 Output / Sales Monopoly Welfare implications of monopolies Costs / Revenue MC £7 AC The value of the grey shaded triangle represents the total welfare loss to society – sometimes referred to as the ‘deadweight welfare loss’. £3 AR MR Q2 Q1 Output / Sales Contestable Markets • Theory developed by William J. Baumol, John Panzar and Robert Willig (1982) • Helped to fill important gaps in market structure theory • Perfectly contestable market – the pure form – not common in reality but a benchmark to explain firms’ behaviours Contestable Markets • Key characteristics: – Firms’ behaviour influenced by the threat of new entrants to the industry – No barriers to entry or exit – No sunk costs – Firms may deliberately limit profits made to discourage new entrants – entry limit pricing – Firms may attempt to erect artificial barriers to entry – e.g… Contestable Markets • Over capacity – provides the opportunity to flood the market and drive down price in the event of a threat of entry • Aggressive marketing and branding strategies to ‘tighten’ up the market • Potential for predatory or destroyer pricing • Find ways of reducing costs and increasing efficiency to gain competitive advantage Contestable Markets • ‘Hit and Run’ tactics – enter the industry, take the profit and get out quickly (possible because of the freedom of entry and exit) • Cream-skimming – identifying parts of the market that are high in value added and exploiting those markets Contestable Markets • Examples of markets exhibiting contestability characteristics: – Financial services – Airlines – especially flights on domestic routes – Computer industry – ISPs, software, web development – Energy supplies – The postal service? The Goal Of Profit Maximization • To analyze decision making at the firm, let’s start with a very basic question – What is the firm trying to maximize? • A firm’s owners will usually want the firm to earn as much profit as possible • We will view the firm as a single economic decision maker whose goal is to maximize its owners’ profit • Why? – Managers who deviate from profit-maximizing for too long are typically replaced either by • Current owners or • Other firms who acquire the underperforming firm and then replace management team with their own – Many managers are well trained in tools of profit-maximization Understanding Profit: Two Definitions of Profit • Profit is defined as the firm’s sales revenue minus its costs of production • If we deduct only costs recognized by accountants, we get one definition of profit – Accounting profit = Total revenue – Accounting costs • A broader conception of costs (opportunity costs) leads to a second definition of profit – Economic profit = Total revenue – All costs of production – Or Total revenue – (Explicit costs + Implicit costs) Why Are There Profits? • Economists view profit as a payment for two necessary contributions • Risk-taking – Someone—the owner—had to be willing to take the initiative to set up the business • This individual assumed the risk that business might fail and the initial investment be lost – Innovation • In almost any business you will find that some sort of innovation was needed to get things started The Firm’s Constraints: The Demand Constraint • Demand curve facing firm is a profit constraint – Curve that indicates for different prices, quantity of output customers will purchase from a particular firm • Can flip demand relationship around – Once firm has selected an output level, it has also determined the maximum price it can charge • Leads to an alternative definition – Shows maximum price firm can charge to sell any given amount of output Total Revenue • The total inflow of receipts from selling a given amount of output • Each time the firm chooses a level of output, it also determines its total revenue – Why? • Because once we know the level of output, we also know the highest price the firm can charge • Total revenue—which is the number of units of output times the price per unit—follows automatically The Cost Constraint • Every firm struggles to reduce costs, but there is a limit to how low costs can go – These limits impose a second constraint on the firm • The firm uses its production function, and the prices it must pay for its inputs, to determine the least cost method of producing any given output level • For any level of output the firm might want to produce – It must pay the cost of the “least cost method” of production The Total Revenue And Total Cost Approach • At any given output level, we know – How much revenue the firm will earn – Its cost of production • Loss – A negative profit—when total cost exceeds total revenue • In the total revenue and total cost approach, the firm calculates Profit = TR – TC at each output level – Selects output level where profit is greatest The Marginal Revenue and Marginal Cost Approach • Marginal revenue –Change in total revenue from producing one more unit of output • MR = ΔTR / ΔQ • Tells us how much revenue rises per unit increase in output The Marginal Revenue and Marginal Cost Approach • Important things to notice about marginal revenue – When MR is positive, an increase in output causes total revenue to rise – Each time output increases, MR is smaller than the price the firm charges at the new output level • When a firm faces a downward sloping demand curve, each increase in output causes – Revenue gain • From selling additional output at the new price – Revenue loss • From having to lower the price on all previous units of output – Marginal revenue is therefore less than the price of the last unit of output Using MR and MC to Maximize Profits • Marginal revenue and marginal cost can be used to find the profit-maximizing output level – Logic behind MC and MR approach • An increase in output will always raise profit as long as marginal revenue is greater than marginal cost (MR > MC) – Converse of this statement is also true • An increase in output will lower profit whenever marginal revenue is less than marginal cost (MR < MC) – Guideline firm should use to find its profit-maximizing level of output • Firm should increase output whenever MR > MC, and decrease output when MR < MC Figure 2(a): Profit Maximization Dollars $3,500 TC 3,000 2,500 Profit at 5 Units 2,000 Profit at 3 Units 1,500 1,000 TR DTR from producing 2nd unit 500 Total Fixed Cost Profit at 7 Units DTR from producing 1st unit 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Output Figure 2(b): Profit Maximization Dollars 600 MC 500 400 300 200 100 0 –100 –200 1 2 3 profit rises 4 5 6 7 profit falls 8 Output MR The MR and MC Approach Using Graphs • Figure 2 also illustrates the MR and MC approach to maximizing profits • Can summarize MC and MR approach – To maximize profits the firm should produce level of output closest to point where MC = MR • Level of output at which the MC and MR curves intersect • This rule is very useful—allows us to look at a diagram of MC and MR curves and immediately identify profit-maximizing output level An Important Proviso • Important exception to this rule – Sometimes MC and MR curves cross at two different points – In this case, profit-maximizing output level is the one at which MC curve crosses MR curve from below What About Average Costs? • Different types of average cost (ATC, AVC, and AFC) are irrelevant to earning the greatest possible level of profit – Common error—sometimes made even by business managers—is to use average cost in place of marginal cost in making decisions • Problems with this approach – ATC includes many costs that are fixed in short-run—including cost of all fixed inputs such as factory and equipment and design staff – ATC changes as output increases • Correct approach is to use the marginal cost and to consider increases in output one unit at a time – Average cost doesn’t help at all; it only confuses the issue • Average cost should not be used in place of marginal cost as a basis for decisions Dealing With Losses: The Short Run and the Shutdown Rule • You might think that a loss-making firm should always shut down its operation in the short run – However, it makes sense for some unprofitable firms to continue operating • The question is – Should this firm produce at Q* and suffer a loss? • The answer is yes—if the firm would lose even more if it stopped producing and shut down its operation • If, by staying open, a firm can earn more than enough revenue to cover its operating costs, then it is making an operating profit (TR > TVC) – Should not shut down because operating profit can be used to help pay fixed costs – But if the firm cannot even cover its operating costs when it stays open, it should shut down Dealing With Losses: The Short-Run and the Shutdown Rule • Guideline—called the shutdown rule—for a lossmaking firm – Let Q* be output level at which MR = MC – Then in the short-run • If TR > Q* firm should keep producing • If TR < Q* firm should shut down • If TR = Q* firm should be indifferent between shutting down and producing • The shutdown rule is a powerful predictor of firms’ decisions to stay open or cease production in shortrun Figure 4(a): Loss Minimization Dollars TFC Q* Output Figure 4(b): Loss Minimization Dollars MC Q* MR Output Figure 5: Shut Down Dollars TC TVC Loss at Q* TFC TR TFC Q* Output The Long Run: The Exit Decision • We only use term shut down when referring to short-run • If a firm stops production in the long-run it is termed an exit • A firm should exit the industry in long- run – When—at its best possible output level—it has any loss at all Using The Theory: Getting It Wrong—The Failure of Franklin National Bank • In the mid-1970’s, Franklin National Bank—one of the largest banks in the United States—went bankrupt • In mid-1974, John Sadlik, Franklin’s CFO, asked his staff to compute average cost to bank of a dollar in loanable funds – Determined to be 7¢ – At the time, all banks—including Franklin—were charging interest rates of 9 to 9.5% to their best customers – Ordered his loan officers to approve any loan that could be made to a reputable borrower at 8% interest Using The Theory: Getting It Wrong—The Failure of Franklin National Bank • Where did Franklin get the additional funds it was lending out? – Were borrowed not at 7%, the average cost of funds, but at 9 to 11%, the cost of borrowing in the federal funds market • Not surprisingly, these loans—which never should have been made—caused Franklin’s profits to decrease – Within a year the bank had lost hundreds of millions of dollars – This, together with other management errors, caused bank to fail Using The Theory: Getting It Right—The Success of Continental Airlines • Continental Airlines was doing something that seemed like a horrible mistake – Yet Continental’s profits—already higher than industry average—continued to grow • A serious mistake was being made by the other airlines, not Continental – Using average cost instead of marginal cost to make decisions • Continental’s management, led by its vice-president of operations, had decided to try marginal approach to profit Macroeconomics • Macroeconomics is the study of the economy as a whole. Its goal is to explain the economic changes that affect many households, firms, and markets at once. Macroeconomics • Macroeconomics answers questions like the following: Why is average income high in some countries and low in others? Why do prices rise rapidly in some time periods while they are more stable in others? Why do production and employment expand in some years and contract in others? The Economy’s Income and Expenditure When judging whether the economy is doing well or poorly, it is natural to look at the total income that everyone in the economy is earning. What is National Income? • National income measures the total value of goods and services produced within the economy over a period of time • National Income can be calculated in three main ways • 1. The sum of factor incomes earned in production • 2. Aggregate demand for goods and services • 3. The sum of value added from each productive sector of the economy Why is national income important? • Measuring the level and rate of growth of national income (Y) is important to economists when they are considering: – Economic growth and where a country is in the business cycle – Changes to average living standards of the population – Looking at the distribution of national income (i.e. measuring income and wealth inequalities) The Economy’s Income and Expenditure • For an economy as a whole, income must equal expenditure because: Every transaction has a buyer and a seller. Every dollar of spending by some buyer is a dollar of income for some seller. Gross Domestic Product • • Gross domestic product (GDP) is a measure of the income and expenditures of an economy. It is the total market value of all final goods and services produced within a country in a given period of time. The Circular-Flow Diagram The equality of income and expenditure can be illustrated with the circular-flow diagram. The Circular-Flow Diagram Revenue Goods & Services sold Market for Goods and Services Firms Spending Goods & Services bought Households Inputs for production Wages, rent, and profit Market for Factors of Production Labor, land, and capital Income The Measurement of GDP GDP is the market value of all final goods and services produced within a country in a given period of time. The Measurement of GDP • • • Output is valued at market prices. It records only the value of final goods, not intermediate goods (the value is counted only once). It includes both tangible goods (food, clothing, cars) and intangible services (haircuts, housecleaning, doctor visits). The Measurement of GDP • • It includes goods and services currently produced, not transactions involving goods produced in the past. It measures the value of production within the geographic confines of a country. The Measurement of GDP • It measures the value of production that takes place within a specific interval of time, usually a year or a quarter (three months). What Is Counted in GDP? GDP includes all items produced in the economy and sold legally in markets. What Is Not Counted in GDP? • • GDP excludes most items that are produced and consumed at home and that never enter the marketplace. It excludes items produced and sold illicitly, such as illegal drugs. Other Measures of Income • • • • • Gross National Product (GNP) Net National Product (NNP) National Income Personal Income Disposable Personal Income Gross National Product • • Gross national product (GNP) is the total income earned by a nation’s permanent residents (called nationals). It differs from GDP by including income that our citizens earn abroad and excluding income that foreigners earn here. Net National Product (NNP) • • Net National Product (NNP) is the total income of the nation’s residents (GNP) minus losses from depreciation. Depreciation is the wear and tear on the economy’s stock of equipment and structures. National Income • • National Income is the total income earned by a nation’s residents in the production of goods and services. It differs from NNP by excluding indirect business taxes (such as sales taxes) and including business subsidies. Personal Income • • • Personal income is the income that households and noncorporate businesses receive. Unlike national income, it excludes retained earnings, which is income that corporations have earned but have not paid out to their owners. In addition, it includes household’s interest income and government transfers. Disposable Personal Income • • Disposable personal income is the income that household and noncorporate businesses have left after satisfying all their obligations to the government. It equals personal income minus personal taxes and certain nontax payments. The Components of GDP GDP (Y ) is the sum of the following: Consumption (C) Investment (I) Government Purchases (G) Net Exports (NX) Y = C + I + G + NX The Components of GDP • Consumption (C): The spending by households on goods and services, with the exception of purchases of new housing. • Investment (I): The spending on capital equipment, inventories, and structures, including new housing. The Components of GDP • Government Purchases (G): The spending on goods and services by local, state, and federal governments. Does not include transfer payments because they are not made in exchange for currently produced goods or services. • Net Exports (NX): Exports minus imports. GDP and Its Components (1998) Total (in billions of dollars) Per Person (in dollars) % of Total Gross domestic product, Y $8,511 $31,522 100 percent Consumption, C 5,808 21,511 68 Investment, I 1,367 5,063 16 Government purchases, G 1,487 5,507 18 Net exports, NX -151 -559 -2 GDP and Its Components (1998) GDP and Its Components (1998) Consumption 68 % GDP and Its Components (1998) Investment 16% Consumption 68 % GDP and Its Components (1998) Investment 16% Consumption 68 % Government Purchases 18% GDP and Its Components (1998) Government Purchases Investment Net Exports 18% 16% -2 % Consumption 68 % Real versus Nominal GDP • • Nominal GDP values the production of goods and services at current prices. Real GDP values the production of goods and services at constant prices. Real versus Nominal GDP An accurate view of the economy requires adjusting nominal to real GDP by using the GDP deflator. GDP Deflator • • The GDP deflator measures the current level of prices relative to the level of prices in the base year. It tells us the rise in nominal GDP that is attributable to a rise in prices rather than a rise in the quantities produced. GDP Deflator The GDP deflator is calculated as follows: Nominal GDP GDP deflator = 100 Real GDP Converting Nominal GDP to Real GDP Nominal GDP is converted to real GDP as follows: (Nominal GDP20xx ) Real GDP20xx = X 100 (GDP deflator20xx ) Real and Nominal GDP Year Price of Hot dogs Quantity of Hot dogs Price of Hamburgers Quantity of Hamburgers 2001 $1 100 $2 50 2002 $2 150 $3 100 2003 $3 200 $4 150 Real and Nominal GDP Calculating Nominal GDP: 2001 ($1 per hot dog x 100 hot dogs) + ($2 per hamburger x 50 hamburgers) = $200 2002 ($2 per hot dog x 150 hot dogs) + ($3 per hamburger x 100 hamburgers) = $600 2003 ($3 per hot dog x 200 hot dogs) + ($4 per hamburger x 150 hamburgers) = $1200 Real and Nominal GDP Calculating Real GDP (base year 2001): 2001 ($1 per hot dog x 100 hot dogs) + ($2 per hamburger x 50 hamburgers) = $200 2002 ($1 per hot dog x 150 hot dogs) + ($2 per hamburger x 100 hamburgers) = $350 2003 ($1 per hot dog x 200 hot dogs) + ($2 per hamburger x 150 hamburgers) = $500 Real and Nominal GDP Calculating the GDP Deflator: 2001 ($200/$200) x 100 = 100 2002 ($600/$350) x 100 = 171 2003 ($1200/$500) x 100 = 240 Real GDP in the United States Billions of 1992 Dollars (Periods of falling real GDP) 8,000 7,000 6,000 5,000 4,000 3,000 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 GDP and Economic Well-Being • • GDP is the best single measure of the economic well-being of a society. GDP per person tells us the income and expenditure of the average person in the economy. GDP and Economic Well-Being • • Higher GDP per person indicates a higher standard of living. GDP is not a perfect measure of the happiness or quality of life, however. GDP and Economic Well-Being • Some things that contribute to well-being are not included in GDP. The value of leisure. The value of a clean environment. The value of almost all activity that takes place outside of markets, such as the value of the time parents spend with their children and the value of volunteer work. GDP, Life Expectancy, and Literacy Country Real GDP per Person (1997) Life Expectancy United States $29,010 77 years 99% Japan 24,070 80 99 Germany 21,260 77 99 Mexico 8,370 72 90 Brazil 6,480 67 84 Russia 4,370 67 99 Indonesia 3,490 65 85 China 3,130 70 83 India 1,670 63 53 Pakistan 1,560 64 41 Bangladesh 1,050 58 39 920 50 59 Nigeria Adult Literacy Summary • • Because every transaction has a buyer and a seller, the total expenditure in the economy must equal the total income in the economy. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) measures an economy’s total expenditure on newly produced goods and services and the total income earned from the production of these goods and services. Summary • • GDP is the market value of all final goods and services produced within a country in a given period of time. GDP is divided among four components of expenditure: consumption, investment, government purchases, and net exports. Summary • • Nominal GDP uses current prices to value the economy’s production. Real GDP uses constant base-year prices to value the economy’s production of goods and services. The GDP deflator--calculated from the ratio of nominal to real GDP--measures the level of prices in the economy. Summary • • GDP is a good measure of economic wellbeing because people prefer higher to lower incomes. It is not a perfect measure of well-being because some things, such as leisure time and a clean environment, aren’t measured by GDP. Graphical Review The Circular-Flow Diagram Revenue Goods & Services sold Market for Goods and Services Firms Spending Goods & Services bought Households Inputs for production Wages, rent, and profit Market for Factors of Production Labor, land, and capital Income GDP and Its Components (1998) Government Purchases Investment Net Exports 18% 16% -2 % Consumption 68 %