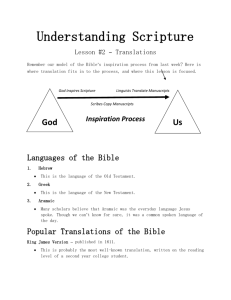

William Tyndale

advertisement

Introduction William Tyndale (sometimes spelled Tynsdale,Tindall, Tindill, Tyndall; c. 1492 – 1536) was an English scholar who became a leading figure in Protestant reform in the years leading up to his execution. He is remembered for his translation of the Bible into English. Tyndale's translation was the first English Bible to draw directly from Hebrew and Greek texts, the first English one to take advantage of the printing press, and first of the new English Bibles of the Reformation. Tyndale began a Bachelor of Arts degree at Magdalen Hall (later Hertford College) of Oxford University in 1506 and received his B.A. in 1512; the same year becoming a subdeacon. He was made Master of Arts in July 1515 and was held to be a man of virtuous disposition, leading an unblemished life. The M.A. allowed him to start studying theology, but the official course did not include the systematic study of Scripture. He was a gifted linguist, over the years becoming fluent in French, Greek, Hebrew, German, Italian, Latin, and Spanish, in addition to his native English. Tyndale became chaplain to the house of Sir John Walsh at Little Sodbury and tutor to his children in about 1521. His opinions proved controversial to fellow clergymen, and around 1522 he was called before John Bell, the Chancellor of the Diocese of Worcester, though no formal charges were laid. After the harsh meeting with Bell and other church leaders, and near the end of Tyndale's time at Little Sodbury, John Foxe describes an argument with a "learned" but "blasphemous" clergyman, who had asserted to Tyndale that, "We had better be without God's laws than the Pope's." Tyndale left for London in 1523 to seek permission to translate the Bible into English. He requested help from Bishop Cuthbert Tunstall, a wellknown classicist who had praised Erasmus after working together with him on a Greek New Testament. The bishop, however, declined to extend his patronage, telling Tyndale he had no room for him in his household. He then left England and landed on the continent, perhaps at Hamburg, in the spring of the year 1524, possibly travelling on to Wittenberg. At this time, possibly in Wittenberg, he began translating the New Testament, completing it in 1525, with assistance from Observant friar William Roy. In 1525, publication of the work by Peter Quentell, in Cologne, was interrupted by the impact of anti-Lutheranism. It was not until 1526 that a full edition of the New Testament was produced by the printer Peter Schoeffer in Worms, a free imperial city then in the process of adopting Lutheranism. The book was smuggled into England and Scotland, and was condemned in October 1526 by Tunstall, who issued warnings to booksellers and had copies burned in public. Cardinal Wolsey condemned Tyndale as a heretic, his first mention in open court as a heretic being in January 1529. In 1530, he wrote The Practyse of Prelates, opposing Henry VIII's planned divorce from Catherine of Aragon, in favour of Anne Boleyn, on the grounds that it was unscriptural and was a plot by Cardinal Wolsey to get Henry entangled in the papal courts of Pope Clement VII. Eventually, Tyndale was betrayed by Henry Phillips to the imperial authoritiesseized in Antwerp in 1535 and held in the castle of Vilvoorde near Brussels. He was tried on a charge of heresy in 1536 and condemned to death, despite Thomas Cromwell's intercession on his behalf. Tyndale "was strangled to death while tied at the stake, and then his dead body was burned". Tyndale's final words, spoken "at the stake with a fervent zeal, and a loud voice", were reported as "Lord! Open the King of England's eyes.“ Within four years, at the same king's behest, four English translations of the Bible were published in England, including Henry's official Great Bible. All were based on Tyndale's work. Impact on the English Language In translating the Bible, Tyndale introduced new words into the English language, and many were subsequently used in the King James Bible: Jehovah (from a transliterated Hebrew construction in the Old Testament; composed from the Tetragrammaton YHWH) Passover (as the name for the Jewish holiday, Pesach or Pesah) scapegoat (the goat that bears the sins and iniquities of the people in Leviticus, Chapter 16) As well as individual words, Tyndale also coined such familiar phrases as: lead us not into temptation but deliver us from evil knock and it shall be opened unto you twinkling of an eye (another translation from Luther) a moment in time fashion not yourselves to the world seek and you shall find ask and it shall be given you judge not that you not be judged the word of God which liveth and lasteth forever let there be light (Luther translated Genesis 1,3 as: Es werde Licht, which would be word for word translated: It will be light) the powers that be my brother's keeper the salt of the earth a law unto themselves filthy lucre it came to pass gave up the ghost the signs of the times the spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak (which is like Luther's translation of Mathew 26,41) live and move and have our being fight the good fight Controversy Over New Words and Phrases The hierarchy of the Roman Catholic Church did not approve of some of the words and phrases introduced by Tyndale, such as "overseer", where the it would have understood as "bishop," "elder" for "priest," and "love" rather than "charity.“ Tyndale, citing Erasmus, contended that the Greek New Testament did not support the traditional Roman Catholic readings. More controversially, Tyndale translated the Greek "ekklesia," (literally "called out ones“) as "congregation" rather than "Church." It has been asserted this translation choice "was a direct threat to the Church's ancient—but so Tyndale here made clear, nonscriptural—claim to be the body of Christ on earth. To change these words was to strip the Church hierarchy of its pretensions to be Christ's terrestrial representative, and to award this honor to individual worshipers who made up each congregation. Contention from Roman Catholics came not only from real or perceived errors in translation but also a fear of the erosion of their social power if Christians could read the bible in their own language. Thomas More commented that searching for errors in the Tyndale Bible was similar to searching for water in the sea, and charged Tyndale's translation of Obedience of a Christian Man with having about a thousand falsely translated errors. Bishop Cuthbert Tunstall of London declared that there were upwards of 2,000 errors in Tyndale's Bible. Tunstall in 1523 had denied Tyndale the permission required under the Constitutions of Oxford (1409), which were still in force, to translate the Bible into English. In response to allegations of inaccuracies in his translation in the New Testament, Tyndale in thePrologue to his 1525 translation wrote that he never intentionally altered or misrepresented any of the Bible in his translation, but that he had sought to "interpret the sense of the scripture and the meaning of the spirit. William Tyndale: The Father of English Prose The King James Bible, since its publication in 1611, has had a profound influence on the development of the English language, not only in the words and phrases that it employed but also in the syntax and grammatical usages that it rendered into the English vernacular. Modern literary and linguistic scholarship has certainly acknowledged the debt the English language owes to the K.J.B. or Authorized Version but very little credit seems to be given to the individual on whose work over 80 percent of the A.V. relied, William Tyndale. Tyndale’s early translations (his first translation of the New Testament was published outside of England in 1525) were based on the premise that “…it was impossible to stablysh the laye people eyes in their mother tonge, that they might se the precesse ordre in any truth excepte the scripture were paynly layed before their and meaninge of the text”. It was a belief for which he would eventually be asked to give his life. William Tyndale’s influence, not only on the early translations of the Bible into English, but also on the development of an Early English Modern prose has been significant enough to earn him the title of “The father of English Prose”. Tyndale was born in Catholic England in approximately 1492, a time of growing political and religious unrest, not only in England but also throughout most of Europe. The seeds of the Protestant reformation had been planted only a few years earlier during the Great Schism (1378-1417) during which time, two popes competed for the authority of the Church and as representatives of God’s divine will. The schism greatly undermined the authority of the pope and led the reformers to question, if the pope’s word was no longer infallible, on what authority could the Christian faith be built. The alternative authority that the reformers were looking for was found in the Bible itself. In 1409 Archbishop Thomas Arundel had banned the reading of the vernacular scripture and, as a result, the only scripture used in religious ceremonies was the Latin Vulgate based on St. Jerome’s translation. Not only was the scripture read in Latin which no one but the educated clergy understood, the service itself was performed in Latin. Tyndale, and other reformers, argued that the Church had degenerated into an empty form and that mass had become, for most participants, a meaningless ceremony. A number of other factors also played an important part in the pivotal role that Tyndale was to play in the development of the English language. Concomitant to the developments of the Protestant reformation was the rise of academic humanism as opposed to the scholasticism that had dominated the universities and academia for some time. With respects to the impetus towards translating the Latin Vulgate into English, the emphasis turned towards translating texts within a historical context and a return to the original language texts. This movement was resisted in the universities in a manner similar to that of the Church as it eroded the position of those in the universities whose authority lay with the medieval scholastic curriculum. There was also an increased knowledge of the original biblical languages. Much of the debate over the place of a vernacular scripture that took place between the Catholic Church and Tyndale was performed by Thomas More who fought vehemently against Tyndale’s translations and their implied associations with Martin Luther and the “heresies” of the reformation. More and the Church strongly opposed the translations into English by individuals because so much of the translations were open to interpretation, interpretations that could significantly alter the teachings of the church. Much of this debate surrounds the nature of the English language itself and the direction it was to take in the next few decades. In fact, England, in the 16th century was country of various vernaculars and dialects and there was as of yet no fully accepted English standard but here, Tyndale argues that, not only is English adequate as a language as a vehicle for God’s word, it was in fact superior to Latin. Tyndale also makes use of the strengths of native alliteration and repetition. Mueller goes on further to argue that Tyndale’s elimination of clausal subordination had far reaching consequences as “within fifty years, the staple of prose compositions become no longer asymmetric and recursive clausal conjunction but, rather, sentence forms of a binary, symmetric, and even schematic cast”. The reasons for Tyndale’s influence over the development of the English language, not only directly but also via the A.V., are numerous. First, there was little other available reading material and the Bible remained the chief written source of formal English for many well into the 19th century. The A.V. had a profound influence not only on writers like Milton, George Fox and John Bunyan, but also on 19th and 20th century writers like George Eliot, T.S. Eliot, Thomas Hardy, Rudyard Kipling, etc. The OED cites Tyndale over 1700 times (this number should be significantly higher if James Clark argues correctly that many of the citations attributed to Miles Cloverdale are actually Tyndale’s) and he is responsible for words such as ‘beautiful’ rather than the more common ‘belle’ or ‘fair’. Many of the phrases he uses appear to be of the popular, semi-proverbial kind such as, “eat the poore out of house and harbour” and “kysse the rodde”. He is also responsible for such time-honoured phrases as "let there be light," (Genesis 1), "the powers that be," (Romans 13), "my brother's keeper," (Genesis 4), "the salt of the earth," (Matthew 5), "a law unto themselves," (Romans 2), "filthy lucre" (1 Timothy 3) and, "fight the good fight"(1 Timothy 6). The Fate of William Tyndale Yet, for all of his effort, and perhaps as a profound testament to the power of his linguistic ability, he was strangled and burned at the stake in Brussels in 1536. But, if we are to accept, as the editors of The Oxford Companion to the English Language suggest, that the 1611 translation of the Bible stands as a landmark in the evolution of the English language and that its “verbal beauty is unsurpassed in the whole of English literature” then certainly most of that credit belongs to William Tyndale.