francis-matthew

advertisement

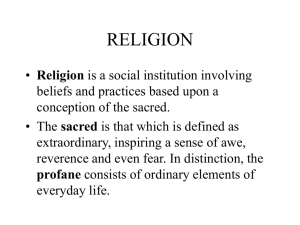

iGov workshop on Islam and Religious Norms in the Public Sphere Return? It never left. Exploring the ‘sacred’ as a resource for bridging the gap between the religious and the secular Matthew Francis Kim Knott Introduction This paper draws on a critical discussion of the assumptions underlying both the secularization thesis as well as the contemporary discussion of religion in the public sphere. Building on our own research as well as a report we co-authored (as part of a wider team) for the UK government, we demonstrate both the need for a paradigmatic shift in understanding how religion and secularity relate to each other and highlight practical policy benefits of adopting such an approach. 1 We start by critiquing the dominant theoretical paradigm for explaining religious/secular relations in modernity: the secularization thesis and assumed constructs of religion and secularity. We then move on to explain how the concept of the ‘sacred’ can be seen to signal deeply-held values on both sides of the religious/secular distinction. Moving on from this theoretical discussion, we provide a resource for determining the location of the sacred within religious/secular ideologies, through suggesting a matrix of markers than can be used to identify and capture data relating to these deeplyheld values. We apply this matrix to some examples, to show how the presence of the sacred within contemporary debates can be mapped out. Recognizing the sacred as both secular and religious opens up constructive potential for serious democratic debate between differing ideological camps and we conclude by offering some examples of the value of this approach for policy makers and analysts. Constructions of religion and secularity The secularization thesis sets out that religion, since the enlightenment, has been of decreasing social significance. The withdrawal of religion from the public sphere has been understood to be a decline in the influence of religious values and institutions on society. Whether this decline is the result of the waning of religious belief,2 or the retreat of beliefs from the public sphere to the private world of individuals3 has been contested. However, despite varying positions on the continuing resilience of some form of religious belief the arguments are, more or less, framed in relation to the secularization thesis. Whilst the thesis in its contemporary form has found a place in academic literature since the 1960s, its roots can be traced back through the founders of the sociological discipline - Comte, Durkheim and Weber all framed their discussions within a belief of the incompatibility of religious institutions Matthew D Francis, “Mapping the sacred: understanding the move to violence in religious and non religious groups” (PhD Dissertation, Leeds: University of Leeds, Forthcoming); Kim Knott, The location of religion: a spatial analysis (London: Equinox, 2005); Kim Knott et al., The roots, practices and consequences of terrorism : a literature review of research in the Arts & Humanities (Leeds: University of Leeds, October 2006), http://www.leeds.ac.uk//trs/documents/University%20of%20Leeds%20terrorism%20lit%20review%20for%20the%20H O.pdf. 2 Steve Bruce, God is dead: secularization in the West (Oxford: Blackwell, 2002). 3 Grace Davie, Religion in Britain since 1945: believing without belonging (Oxford: Blackwell, 1994). 1 Department of Theology and Religious Studies University of Leeds, Leeds, LS2 9JT, UK iGov workshop on Islam and Religious Norms in the Public Sphere within modernity - and further back still to the ideals of the enlightenment and its promotion of reason over superstition. The assumed dominance of modern secular ideals over religious values, which has formed the basis of the academic conception of secularization,4 has been adopted by popular European discourses in government and the media5 and, to a lesser extent, within mainstream perceptions in the US.6 These assumptions regarding the decline of religious belief and its significance have become so commonplace that the ‘return’ of the sacred in domestic and international arenas, from debates on the wearing of religious symbols in the UK,7 to religious legitimations of terrorist actions,8 has elicited widespread surprise – even within academia.9 However, despite the acceptance in popular assumptions of the secularization thesis, some academics have questioned the validity of the theory to account for the relationship between religion and society,10 including those who previously championed it.11 In our critique of it we are not primarily interested in its explanatory efficacy (though this is brought into question by our findings). Rather, we start by questioning the conceptualization of ‘religious’ and ‘secular’ which, in turn, subvert the assumption that the former has been subsumed by the latter. In contemporary accounts of ‘religion’, especially within discussions of the secularization thesis, the concepts of ‘religion’ and ‘secular’ are assumed to be oppositional epistemological categories separated by an impermeable boundary. Institutions, values, ideas, places and people are assumed to fall into either one or the other category – church and state; faith and reason; belief and science – and invariably, from the American constitution to the French educational system and the British National Health Service, this separation has led to the marginalization of religion in the public sphere. Likewise, when this boundary is threatened with transgression, it is seen as an imposition that should be forbidden, hence the opposition to an established church in America and to public displays of religiosity in the clothing of school pupils in France or nurses in the UK. Within these debates lies an idea of what constitutes religious forms and their opposite, the secular. However, the idea of ‘religion’ as a reified concept can be seen to have its place within the development of European Christianity, for example in the distinction between religious and secular vocations,12 and in the separation from ‘secular’ ideals in the burgeoning atheism of the European Roy Wallis and Steve Bruce, “Secularization: the orthodox model,” in Religion and modernization: sociologists and historians debate the secularization thesis, ed. Steve Bruce (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992), 8-30. 5 A senior adviser to Tony Blair, former British Prime Minister, famously declared that “we [the government] don’t do God” – see the 2003 BBC article by Roger Childs at (http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/3301925.stm) where he refers both to this utterance and the ‘howls of derision’ from the press when Blair invoked religious imagery. 6 R. Stephen Warner, “Work in progress toward a new paradigm for the sociological study of religion in the United States,” American Journal of Sociology 98, no. 5 (1993): 1046. 7 BBC, “Row over nurse wearing crucifix,” BBC, September 20, 2009, sec. Devon, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/devon/8265321.stm. 8 Osama bin Laden, “Oath to America,” in The Al Qaeda Reader, ed. Raymond Ibrahim (New York: Doubleday, 2007), 192-195. 9 Peter L Berger, “The descularization of the world: a global overview,” in The desecularization of the world: resurgent religion and world politics, ed. Peter L Berger (Washington D.C.: Ethics and Public Policy Center, 1999), 1-2. 10 David Martin, The religious and the secular: studies in secularization (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1969); David Martin, “The secularization issue: prospect and retrospect,” The British Journal of Sociology 42, no. 3 (1991): 465-474. 11 Peter L Berger, The sacred canopy: elements of a sociological theory of religion (New York: Doubleday, 1967); Berger, “The descularization of the world: a global overview.” 12 Richard King, Orientalism and religion: postcolonial theory, India and “the Mystic East” (London: Routledge, 1999), 35-41. 4 Department of Theology and Religious Studies University of Leeds, Leeds, LS2 9JT, UK iGov workshop on Islam and Religious Norms in the Public Sphere Enlightenment. 13 As such, the oppositional religious/secular binary can be seen to be a relatively recent, and clearly Western, construct. ‘Religion’ is commonly construed in emic terms (by people within Western cultures) as religious institutions, their traditions, beliefs and practices, and those who to a greater or lesser extent adhere to them, and ‘secular’ as all that falls outside this definition.14 However, the discursive division of these two categories suggests that they are interrelated, and as such we propose that they should be located as separate camps within a single epistemological field, as opposed to as an ‘either/or’ dichotomy.15 Furthermore, we argue that the boundary separating them has rarely, in practice, been impermeable and is subject to struggles and movements between them. Tony Blair, for example, former British Prime Minister, rarely discussed religion despite the established status of the Anglican Church, and George Bush, although head of a government with strict separation from any particular religious institution, frequently invoked ‘God’ in matters of state. This field can be portrayed dialectically, with a third, ‘post-secular’ position encompassing those who see the positive in both religious and secular positions, and who move beyond rigid conformity with one or the other or embrace both concepts strategically.16 However, here we will focus solely on dichotomous representations of the religious and secular, and the placement of these positions within the field. Figure 1 – The religious/secular field and its force relationships17 By drawing on the concept of the ‘sacred’, we aim to problematise the discursive distinction between these two camps, and thus to trouble the notion that we are seeing a return to the sacred in contemporary modernity. We will suggest that the ‘sacred’ never left modernity and that a proper exploration of it provides an explanation of its apparent ‘return’ and indeed a clearer understanding of the relationship between religious and secular thought. Before we discuss the concept of the ‘sacred’ in more depth, it is necessary to understand what values differentiate the various positions within the two broad camps of the religious and secular and what drives the various struggles that we witness between exponents in each camp, for example, holders of liberal-secularist positions, and Rodney Stark, “Atheism, faith, and the social scientific study of religion,” Journal of Contemporary Religion 14, no. 1 (1999): 41-62. 14 Knott, The location of religion: a spatial analysis, 59 15 Knott, The location of religion: a spatial analysis, 59-77. 16 Ibid., 71-72 See also a diagrammatical representation of the field in Figure 1. 17 Ibid., 125. 13 Department of Theology and Religious Studies University of Leeds, Leeds, LS2 9JT, UK iGov workshop on Islam and Religious Norms in the Public Sphere religious fundamentalists. We will explore these issues using an example of the persistence of references to the ‘sacred’ in religious and secular discourse, one which also throws into sharp relief the discursive religious/secular struggles within British society.18 In 1988 The Satanic Verses was published,19 quickly leading to protests in various countries, including the UK, on which we shall focus here.20 The vehemence of the British Muslim community’s response is well-known. Many of them felt that their religious symbols had been desecrated, and this led to the book becoming a “litmus-test for distinguishing faith from rejection”21 and so constituted a “boundary between Muslims … and non-Muslims (and thus religion and nonreligion).”22 However, it is also apparent that liberal-secularists who opposed the Muslim protests, also held deeply entrenched and non-negotiable positions. Rushdie, writing in a major British newspaper, noted that he cherished the art of the novel as much as Muslims did their brand of Islam.23 Later, he utilized religious metaphors, in a public lecture entitled Is Nothing Sacred and an essay called In Good Faith. These metaphors were echoed in a pamphlet issued in support by the writer Fay Weldon, Sacred Cows, and also in statements by other liberal-secularists, not least in a joint statement published in the New Statesman on 3rd March 1989:24 We are embattled in the war between the cultural imperatives of Western liberalism, and the fundamentalist interpretations of Islam, both of which seem to claim an abstract and universal authority […] On the one hand there is the liberal opposition to book burning and banning based on the important belief in the freedom of expression and the right to publish and be damned […] On the other side, there exists what has been identified as a Muslim fundamentalist position.25 From these examples it is clear that the debate between the two opposing camps was played out in terms of a struggle, with each vying to assert the undeniable truth of their position and the uncompromising nature of that of their opponents. Interestingly, both invoked the language of the ‘sacred’ and of non-negotiable values. That such language and values were not confined to the religious camp supports our assertion that, irrespective of any decline in religious belief or belonging, the sacred had not disappeared. Understanding the sacred Figure 2 below utilizes the earlier diagram to illustrate the oppositional ideological positions articulated so forcefully during The Satanic Verses controversy. Strong Muslim positions were pitted against equally vociferous secularist ones in a discursive struggle fought out in the public media. With exponents on both sides of the argument drawing on the language of the ‘sacred’ to This example is based on a case-study undertaken by Knott in: “Theoretical and methodological resources for breaking open the secular and exploring the boundary between religion and non-religion,” Historia Religionum 2 (2010): 129-133. 19 Salman Rushdie, The satanic verses (London: Viking, 1988). 20 A summary of the controversy and causes for Muslims’ protests can be found in Malise Ruthven, A satanic affair: Salman Rushdie and the rage of Islam (London: Chatto & Windus, 1990) and; Shabbir Akhtar, Be careful with Muhammad: the Salman Rushdie affair (London: Bellew Publishing, 1989) Responses from around the world can also be found in; Lisa Appignanesi and Sara Maitland, eds., The Rushdie file (London: Fourth Estate, 1989). 21 Akhtar, Be careful with Muhammad: the Salman Rushdie affair, 35. 22 Knott, “Theoretical and methodological resources for breaking open the secular and exploring the boundary between religion and non-religion,” 130. 23 Appignanesi and Maitland, The Rushdie file, 74-75. 24 Kim Knott, “Theoretical and methodological resources for breaking open the secular and exploring the boundary between religion and non-religion”, 131. 25 Appignanesi and Maitland, The Rushdie file, 137-140. 18 Department of Theology and Religious Studies University of Leeds, Leeds, LS2 9JT, UK iGov workshop on Islam and Religious Norms in the Public Sphere represent the importance and non-negotiability of their case, they repeatedly referred to the gulf or boundary between the two positions. Such boundaries can lie dormant, invisible to outsiders, until they are threatened with transgression – as in this case when the deeply held but quietly expressed strength of feeling around the sanctity of the Prophet Muhammad was suddenly challenged and Muslims rose up in protest. Their response led liberal-secularists to come out in defense of Rushdie and his freedom as an author to express himself. In short, secularists realized the sanctity of their own position. Various Muslim positions Various Secularist positions undecided, agnostic, those wishing to bring opposing positions together (Post-secular) Struggles between camps Struggles within camps Figure 2 – The religious/secular field and The Satanic Verses controversy The concept of the ‘sacred’, as utilized in this discussion, finds its genesis within a Durkheimian notion of “things set apart and forbidden”26 although we have developed it in the context of recent spatial and cognitive approaches to the study of religion. In The Location of Religion Knott set out to develop a spatial methodology for locating religion within ‘secular’ contexts in which she modeled the inter-relational and dialectical nature of religious, secular and post-secular positions (see fig 1).27 In an extended case study, whilst noting the capacity of exponents from these different camps to present themselves in opposition to others, she also found that the nature of their arguments and claims had much in common, particularly in so far as they drew on the language of the ‘sacred’ to stake their positions. This observation is supported by the theoretical contributions offered by neo-Durkheimian anthropology, in particular the cognitive/cultural account of Veikko Anttonen. In his discussion of the ‘sacred’ as a category boundary,28 Anttonen argues that the sacred is not confined to the religious context: 26 Émile Durkheim, The elementary forms of religious life (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 46. Knott, The location of religion: a spatial analysis. 28 Veikko Anttonen, “Sacred,” in Guide to the study of religion, ed. Willi Braun and Russell T McCutcheon (London: Cassell, 2000), 271-282. 27 Department of Theology and Religious Studies University of Leeds, Leeds, LS2 9JT, UK iGov workshop on Islam and Religious Norms in the Public Sphere Sacrality is employed as a category-boundary to set things with non-negotiable value apart from things whose value is based on continuous transactions… People participate in sacred making activities and processes of signification according to paradigms given by the belief systems to which they are committed, whether they be religious, national or ideological.29 In acting as a category-boundary, the ‘sacred’ binds together those inside the boundary at the same time as separating them from those outside it. This understanding of the ‘sacred’, unlike the religious/secular distinction, is not a construct of modernity, and indeed “cuts across the modern religion-secular dichotomy”.30 The following diagram reflects this: it shows that attributions of the ‘sacred’ appear everywhere in the field, in all camps – whether secular, religious or post-secular. Secular Religious “sacred” attributions Post-secular Figure 3: The religious/secular field and attributions of the “sacred” The claim that one’s position is non-negotiable can be made by any exponent, according to the beliefs and values inherent in the worldview to which they subscribe. When such a position is strongly articulated – when a sacred boundary is transgressed – then differences are realized, dichotomous stances become apparent and battle-lines are drawn, as in the case of Muslim and secularist protagonists during The Satanic Verses controversy. A resource for identifying ideological positions Understanding where these non-negotiable boundaries lie is essential for policy-makers and analysts in order to understand the potential within society for conflict and thereby to avoid it. Therefore, we suggest a matrix of markers that can be used to assist in this process. Focusing on the public discourse of groups, these markers can be used to identify and capture data relating to key variables, such as the expression of ‘dichotomous world views’ or ‘external legitimating authorities’, that may signal conflict and even suggest capacity for violence. Utilization of this approach may assist in identifying and negotiating the sacred territory of various ideological positions, help in intervention and conflict mediation, and assist in policy formulation in areas such as public order, radicalization and community cohesion. 29 Ibid., 280-281. Timothy Fitzgerald, Discourse on civility and barbarity a critical history of religion and related categories (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 108. 30 Department of Theology and Religious Studies University of Leeds, Leeds, LS2 9JT, UK iGov workshop on Islam and Religious Norms in the Public Sphere An initial matrix of markers was first suggested in the literature review produced by the team at Leeds for the British Home Office in response to the omission we identified in the literature relating to understanding the move to violence in the beliefs of religious groups.31 In order to better explore this topic we suggested further research and some markers which could be used to facilitate this process. The matrix has been further developed by Francis in his exploration of the role of the sacred in the move to violence in religious and secular groups.32 The current list of markers has been developed iteratively through a number of case studies which have focused on violent religious (Aum Shinrikyo, al Qaeda) and secular groups (Red Army Faction) as well as a number of non-violent groups (Agonshu, Hizb ut-Tahrir in Uzbekistan and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee).33 During each case-study, statements made by the groups – in the form of interviews, treatises, propaganda and so on, were coded into the markers. Where new areas for examination became apparent, new markers were developed to capture this information. Some of the markers captured significantly more information than others and we suggest that additional markers could be developed in light of future research topics. The table below lists the matrix of markers of particular relevance to the subject of this paper. An explanation of the key markers follows before we go on to illustrate some of the data that these markers are designed to capture. Name of marker Definition Against Violence Basic Injustice Actual statement renouncing violence A sense of some basic injustice, which is non-accidental (i.e., it expresses the core values, true nature of society and is irredeemable), and which reinforces the sense of opposition/dichotomy – ‘clash of worlds’ Evidence of confrontation within the development of the group, either accidental or intentional Context of Group's Internal Development Context of Group’s Origins/Developme nt Conviction Desire for Social Change Dichotomous World-View Emergency Situation External Legitimating Evidence of confrontation within the wider society within which the group originated and specifically interacted with A deep and incontestable sense of conviction The intended aim of actions for social change, either in a specific area or globally (this does not mean the end of the world, but could mean global conversion to a particular faith or way of ruling.) An oppositional and dichotomous world-view (cosmology) The field of action takes on the character of an emergency situation, through real or a conflation of symbolic and real pressures, leading to the suspension of normal moral codes which regulate and limit action and the justification of emergency forms of action Worldview justified by appeal to legitimating authority external to/transcending the situation (God, religious scriptures, traditions, 31 Knott et al., The roots, practices and consequences of terrorism : a literature review of research in the Arts & Humanities. 32 Francis, “Mapping the sacred: understanding the move to violence in religious and non religious groups.” 33 It is problematic to make hard and fast distinctions between ‘violent’ and ‘non-violent’ labels and Francis (Ibid., Chapter 7) discusses this and the reasons for choosing these groups as ‘non-violent’ examples. Department of Theology and Religious Studies University of Leeds, Leeds, LS2 9JT, UK iGov workshop on Islam and Religious Norms in the Public Sphere Name of marker Definition Authority fundamental human rights or values) Followers Differ from Leader Where a follower consciously (or otherwise) expresses an idea that differs from a leader (or disagrees with). To show where beliefs expressed by leaders are not necessarily all taken on by followers. A clear awareness of the need and/or desire to frame actions within a discourse of ‘revenge’ Involvement in the Cycle of Reciprocal Violence No Common Ground No Innocent ‘Others’ No Justice Available in System Personal Benefit Question of Authority Recognition of Innocence Recourse to Sacrificial / Judicial Processes Symbolic Importance Violent Traditions Wider Struggle An absence of common ground with ‘Others’ allowing meaningful dialogue with other world views A sense that all members of the ‘Other’ group are involved and implicated in the opposition to the good, and so legitimate targets: there is no ‘innocence’ Statement claiming that the group has no recourse to judicial protection Explicit statement of benefits for followers – such as heightened physical or mental abilities, salvation, sense of righteousness, etc. Dispute within an ideology of who has the authoritative view of the historical and contemporary practice of the ideology Recognition that there ARE innocent ‘Others’, and that they should not be targeted Evidence of an attempt to conclude a cycle of violence through a sacrificial/judicial act A sense of symbolic importance given to the present action Evidence of specifically violent traits/influences (imagery/myth) within the traditions/beliefs of the group The present condition/field of action is situated within a wider struggle imbibed with normative value (good vs. evil; right vs. wrong). Table 1 – Matrix of relevant markers The following two markers have particular relevance to the case of The Satanic Verses controversy: Dichotomous World-View External Legitimating Authority34 These will be discussed and illustrated in turn. These and other markers are discussed in more detail in Francis, “Mapping the sacred: understanding the move to violence in religious and non religious groups.” 34 Department of Theology and Religious Studies University of Leeds, Leeds, LS2 9JT, UK iGov workshop on Islam and Religious Norms in the Public Sphere Dichotomous World-View This marker captures values that expound a ‘Them and Us’ mentality and which suggest a worldview influenced by a struggle between opposing forces such as, for example, God versus the Devil, Good versus Evil, Enlightened versus Unenlightened, Believer versus Non-Believer. A group expressing itself in this way views itself as on the side of good, and a clear distinction is made between those within the group and those without. For example, in some Muslim groups those outside of the group may be called ‘kafir’ (someone who does not believe in Allah) a term with negative connotations and which may also entail the threat of punishment. Secular groups, such as the Red Army Faction, also situate their values within a dichotomous world-view and in similar ways to religious groups make a clear distinction between members and their ‘Other’. These distinctions are evidence of the kind of non-negotiable values that groups believe differentiate them from their ‘Other’, and demonstrate the concept of the ‘sacred’ working as a border category. As discussed above, these struggles take place both within and between camps, and the following is a good example of how one Muslim, Salman Ghaffari, the Iranian Ambassador to the Holy See, viewed the struggle surrounding The Satanic Verses as one between all those in the religious camp against those in the secular camp:35 [Interviewer]: In the appeal you made to the Pope on February 15, you describe the Pope as a ‘defender of spirituality and of religion’. Are you thinking perhaps in terms of a kind of Holy Alliance between the Catholic Church and Islam against modern unbelief? [Ghaffari]: This holy union existed from the beginning. Islam has always hoped for this collaboration. Our history shows that Islam and Christianity can live together like brothers. Let us leave aside the ideological conflicts of the past. We hope that Christianity, with the help of Islam, can carry this world toward God and toward faith, preventing all oppression…. In this quotation Ghaffari suggests a dichotomous world view dividing those who have faith (in one God) from those who do not have faith (see Fig. 1). As Islam and Christianity are more commonly presented in mutual distrust and opposition, we can see that this idea of a dichotomous world view can be found to suggest unlikely partnerships and values. This idea, of a division between those with faith and those without, was also found in an open letter by an Indian Muslim MP (Syed Shahabuddin) to the Times of India on the 13th October 1988: 36 Rest assured, Rushdies will come and go but the names of Mohammad, Christ or Buddha will last till the end of time. And soon your Satanic Verses will be laid aside, having served its literary purpose of generating excitement… But the Koran, the Bible and the Gita shall continue to be read by millions and not only read but revered and acted upon. In this quotation, Shahabuddin explicitly invoked all faith (including polytheistic faith) against the secularism which Rushdie was seen to represent. However, Shahabuddin, in the same letter, also brought into play a more common dichotomous view of the world, when he mentions the Crusades: 37 Rushdie ‘the Islamic scholar, the man who studied Islam at university’ has to brag about his Islamic credentials, so that he can convincingly vend his wares in the West, which has not yet 35 This interview was reproduced in Appignanesi and Maitland, The Rushdie file, 82. Ibid., 39. 37 Ibid. 36 Department of Theology and Religious Studies University of Leeds, Leeds, LS2 9JT, UK iGov workshop on Islam and Religious Norms in the Public Sphere laid the ghost of the crusades to rest, but given it a new cultural wrapping which explains why writers like you [Rushdie] are so wanted and pampered. The mention of the Crusades evokes a dichotomy based on Western versus non-Western (in this case, Islamic) values. Understanding this helps explain the response of many critics of The Satanic Verses to what they saw as the Western imposition of their secular values onto the culture and values of those in the former British colonies. It also clarifies how the struggle over The Satanic Verses could be seen to be representative of a power struggle – between Muslims and their ‘Other’, in this case Western powers (and Westernized elites).38 The liberal-secularists also upheld a dichotomous world view, as shown in an article in The Guardian newspaper where the author, the literary editor W L Webb, wrote:39 “For some reason… we seem to have supposed, if we thought about their coexistence at all, that these two tracks of Islamic fundamentalism, and existential, post-Christian modernism would continue on their parallel paths for ever. The wonder is, of course, that the collision didn’t occur before now…” Furthermore, whilst Webb argued that it was necessary to avoid normative reductions of the affair to good versus evil typologies (“[W]e must be careful not to reduce the Rushdie affair to … a simple neo-Victorian opposition between our light and their darkness”) he seems to do exactly that, in his conclusion to the article. He concludes by saying that “No one quite knows how it [coexistence] works when the protagonists, close neighbors in fact, turn to look at each other with a wild surmise and discover their dismaying proximity and incompatibility.” The divisions were stated even more clearly in the following statement published in the New Statesman:40 We are embattled in the war between the cultural imperatives of Western liberalism, and the fundamentalist interpretations of Islam, both of which seem to claim an abstract and universal authority […] On the one hand there is the liberal opposition to book burning and banning based on the important belief in the freedom of expression and the right to publish and be damned […] On the other side, there exists what has been identified as a Muslim fundamentalist position. Here the differing ‘camps’ demonstrated self-defined divisions in how they viewed the world, divisions marked by values relating to the sanctity of the Prophet in Islam, and also by that “frail religion whose faith happens to be the power of words and our willingness to suffer for them”41 in the values of the liberal-secularists. Although we have demonstrated these values in relation to the Rushdie Affair, it is apparent that they still play driving roles in defining positions held by various groups in more contemporary cases, such as the Danish Cartoon Affair, debates over headscarves in France and the Qur’an-burning protests in It was also, of course, part of a struggle on a more mundane level too – Shahabuddin’s outrage over the novel could also be seen as a cynical ploy to win the Muslim vote in the upcoming Indian general elections, as suggested by Kenan Malik, “Exploding the fatwa myths,” www.guardian.co.uk, February 12, 2009, http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2009/feb/09/religion-islam-fatwa-khomeini-rushdie. 39 William L Webb, “The Imam and the scribe,” The Guardian (London, February 17, 1989). 40 Appignanesi and Maitland, The Rushdie file, 137-140. 41 Norman Mailer, as quoted in Richard Webster, A brief history of blasphemy: liberalism, censorship and “the satanic verses” (Southwold: Orwell, 1990), 56. 38 Department of Theology and Religious Studies University of Leeds, Leeds, LS2 9JT, UK iGov workshop on Islam and Religious Norms in the Public Sphere the United States. Understanding the boundaries that mark these divisions foreshadows future conflicts as well as aiding comprehension in how to avoid and/or heal future disagreements. External Legitimating Authority This marker captures justifications attributed to God or another legitimating authority in justifications of violence. In a recent example, bin Laden’s speeches frequently reference Allah as a spiritual justification for the actions of al Qaeda, as seen in the following quotation from one of his speeches:42 God Almighty hit the United States at its most vulnerable spot. He destroyed its greatest buildings. Praise be to God. This marker has also been defined in such a way that it also captures legitimization from nonreligious sources, such as through interpretations of secular ideologues. The value of a legitimating authority which is external to the group represents another non-negotiable aspect of a group’s beliefs: for these legitimations to have any validity for the group they must have an absolute and unquestionable authority as their source. One clear example of how these values were expressed in the Rushdie Affair comes from the Ghaffari interview cited earlier:43 [Interviewer]: Finally, I’d like to ask a hypothetical question about the Rushdie affair, as one man to another. If Mr Rushdie were in this room, unarmed, and you were armed with a pistol, would you pull the trigger without any hesitation? [Ghaffari]: Yes, certainly I would. The law of God is clear. The specific law in this case is also. But why do you find this behaviour strange? If God orders and allows that someone be executed, the carrying out of this divine precept serves to teach all of society. In this case, Ghaffari cites justification for his (hypothetical) actions through their sanction by God. God, as shown in this example, has authority over all of society, not just Muslim society, both directly and through his law. The authoritative status of Islamic law is also referenced in the following quotation, in which Amir Taheri (Iranian journalist and author of a biography of Khomeini) explained the process behind Khomeini’s fatwa against Rushdie:44 He [Khomeini] was told of the contents of The Satanic Verses through an aide and decided that Rushdie was guilty on all three charges, any one of which would carry the death penalty under Islamic law. He was found to be ‘an agent of corruption on earth’, one who has ‘declared war on Allah’ and, last but not least, a murtad – a born Muslim who has abandoned his faith and crossed over to the enemies of Islam. This quotation highlights several important Islamic values which Rushdie is said to have threatened – in terms of moral corruption, insult to Allah and also in abandoning the privileged position of his inherited faith. All of these charges are encompassed within the external legitimacy of Islamic law 42 Paul Chilton, Analysing political discourse : theory and practise (London: Routledge, 2004), 166. Appignanesi and Maitland, The Rushdie file, 82-83. 44 From The Times, London, 13th February 1989, and reproduced in Ibid., 88. 43 Department of Theology and Religious Studies University of Leeds, Leeds, LS2 9JT, UK iGov workshop on Islam and Religious Norms in the Public Sphere and, in concentrating on this area, the marker has drawn out further examples of non-negotiable values. In terms of non-negotiability, this aspect is not stressed much more strongly than in the command to kill, expressed by Khomeini and also explained by Taheri: “Sometimes, true believers must act even before any harm is done to Islam. The prophet is quoted as saying; ‘Kill the harmful ones before they can do harm.’”45 As well as demonstrating the non-negotiability of the Muslim position in regard to the values they felt were under threat, this quotation also cited another external source of legitimation – the Prophet. However, Rushdie too invoked an external legitimating authority, in this case freedom of expression which, he wrote, “is at the very foundation of any democratic society…”46 The concept of a freedom of expression as a universal right formed the basis of much of the liberalsecularist opposition to Muslim protests over The Satanic Verses. But the idea of a democratic society also played an important role, as mentioned by Rushdie, above, and also in a feature article in The Sunday Times:47 Thatcher made it clear that ‘there are no grounds in which the government would consider banning’ the book. ‘It is an essential part of our democratic system that people who act within the law should be able to express their opinions freely.’ These non-negotiable abstract values, and the commitment of those who upheld them, indicate that the sacred was as present in the liberal-secularist discourse as it was in the Islamic values highlighted in the examples above. The secular position was as intractable as that of the Muslim protestors, as shown in Rushdie’s statement that:48 Frankly I wish I had written a more critical book. A religion that claims it is able to behave like this, religious leaders who are able to behave like this, and then say this is a religion that must be above any whisper of criticism – that doesn’t add up. The above examples show how the matrix can be applied to the Rushdie Affair, with some discussion based around two of the markers. The matrix, in its operationalisation of the sacred, can identify and focus attention on the public values of the groups to which it is being applied. In this case, we have chosen the Rushdie Affair as it not only provides examples of Islamic religious values which were publicly expressed in many countries, not just Britain, but also because it is a good example of where secular values were demonstrated to hold the same non-negotiability. This reinforces our claim that the sacred has never been absent, even within secular ideological systems, at the same time as demonstrating a new method of analyzing the presence of religious norms in the public sphere. The sacred, the matrix and public policy Recognizing the sacred as both secular and religious opens up constructive potential for serious democratic debate between differing ideological camps. In the above example we drew on the 45 Ibid., 89. In an open letter to Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, on 7th October 1988 and reproduced in Ibid., 35. 47 From The Sunday Times, London, 19th February 1989 and reproduced in Ibid., 45. 48 Rushdie, writing in The Guardian, London, February 15th 1989, as reproduced in Ibid., 77. 46 Department of Theology and Religious Studies University of Leeds, Leeds, LS2 9JT, UK iGov workshop on Islam and Religious Norms in the Public Sphere values expressed by liberal-secularist defenders of free speech and those who held conservative Islamic values. In doing so we highlighted what is distinctive about the irruption of the ‘sacred’ in public discourse, in both religious and secularized environments, and how such instances may contribute to the construction and maintenance of non-negotiable identities. We argue that this matrix of markers constitutes a methodology that, contributes to public understanding about the importance of sacred beliefs and values for people’s identities; deepens knowledge about ‘secular’ society, its beliefs and values and their relationship to religion; shows how beliefs can be interrogated; and challenges assumptions about the relationship of religion and the secular with reference to the ‘sacred’. The matrix of markers suggested above was constructed as part of a research project to interrogate beliefs in relation to understanding the change in and role of beliefs in the move to violence. Through application of the matrix to the statements of groups it was possible to highlight values which were suggestive of violent potentialities, by exploring the values and the ways in which they were expressed.49 If we had applied the same research question to the Rushdie Affair, we would have expected markers, such as the Violent Traditions marker, to capture information on how such non-negotiable values indicated or legitimated violent responses in the face of threats to the sacred. An example of a statement espousing these values may be found in the interview with Ghaffari, above, where he stated that it was God’s law that Rushdie be killed. Within the context of understanding the move to violence, a better understanding of the violent potentialities of values is a useful outcome. However, this should be tempered with a recognition of the complexities of these values and the differences in their application, from group to group and individual to individual.50 Beyond the question of the move to violence, it is also apparent that a greater understanding of the importance of sacred beliefs and values to the identity of groups would have been of public benefit. Such an understanding could have helped bridge the gap in the discourse between the liberalsecularist and Muslim communities that clashed over The Satanic Verses. Indeed, some authors recognized this at the time. Michael Ignatieff, for example, suggested that the liberal claim to “hold freedom sacred” should be undertaken as “a contestable concept” in the spirit of listening, understanding and enduring offence.51 In this example, it is interesting that Ignatieff argued exactly that the idea of ‘freedom’ should not be viewed as “a holy belief, nor even a supreme value,” in so doing demonstrating his awareness of the potential impermeability of the ‘sacred’ boundary separating the liberal-secularist from Islamic positions. Francis, “Mapping the sacred: understanding the move to violence in religious and non religious groups.” For example, with Islamic norms there are many differing interpretations of teachings that could be said to be violent. Even, for example, between those espoused in many al Qaeda statements and that of Hizb ut-Tahrir in Uzbekistan, the latter which is explored in the works of Emmanuel Karagiannis, “Political Islam in Uzbekistan: Hizb ut-Tahrir al-Islami,” Europe-Asia Studies 58, no. 2 (2006): 261-280; Emmanuel Karagiannis and Clark McCauley, “Hizb ut-Tahrir al-Islami: evaluating the threat posed by a radical Islamic group that remains nonviolent,” Terrorism and Political Violence 18 (2006): 315-334; Vitaly V. Naumkin, Radical Islam in Central Asia: between pen and rifle, The Soviet bloc and after (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2005). In these works the authors suggest that the Islamic values of Hizb ut-Tahrir do not easily suggest the potential for violent action, in contrast to those held by al Qaeda. 51 Michael Ignatieff, “Defenders of Rushdie tied up in knots,” The Observer (London, April 2, 1989). 49 50 Department of Theology and Religious Studies University of Leeds, Leeds, LS2 9JT, UK iGov workshop on Islam and Religious Norms in the Public Sphere Taheri also recognized the non-negotiable nature of such a boundary, in this case in relation to Islam, when he said:52 The entire Islamic system consists of the so-called Hodud, or limits beyond which one should simply not venture. Islam does not recognize unlimited freedom of expression. Call them taboos, if you like, but Islam considers a wide variety of topics as permanently closed. The model that we have suggested – the matrix – allows those interested in the ideological norms of groups to explore such boundaries, and encourages the kind of awareness shown by exponents such as Ignatieff and Taheri. In many cases, simply raising awareness of the nature of these boundaries, even within ‘secular’ society, is a beneficial end for policy-makers. Understanding where potential conflicts might arise, and using that knowledge to act sensitively can bypass such conflict in the first place. It also deepens understanding of the nature of religious values within secular systems, as well of the similarities between systems – in terms of adherence to matters of sacred concern – that are generally seen only in oppositional terms. We suggest that the matrix has utility not only in academic studies of the religious norms in the public and private spheres, but also in policy applications. Through application of the matrix the above benefits could help shape policy to be sensitive to areas of potential ideological nonnegotiability. 52 Appignanesi and Maitland, The Rushdie file, 88-89. Department of Theology and Religious Studies University of Leeds, Leeds, LS2 9JT, UK iGov workshop on Islam and Religious Norms in the Public Sphere Bibliography Akhtar, Shabbir. Be careful with Muhammad: the Salman Rushdie affair. London: Bellew Publishing, 1989. Anttonen, Veikko. “Sacred.” In Guide to the study of religion, edited by Willi Braun and Russell T McCutcheon, 271-282. London: Cassell, 2000. Appignanesi, Lisa, and Sara Maitland, eds. The Rushdie file. London: Fourth Estate, 1989. BBC. “In quotes: Jack Straw on the veil.” BBC, October 6, 2006, sec. Politics. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk_politics/5413470.stm. ———. “Row over nurse wearing crucifix.” BBC, September 20, 2009, sec. Devon. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/devon/8265321.stm. Berger, Peter L. “The descularization of the world: a global overview.” In The desecularization of the world: resurgent religion and world politics, edited by Peter L Berger, 1-18. Washington D.C.: Ethics and Public Policy Center, 1999. ———. The sacred canopy: elements of a sociological theory of religion. New York: Doubleday, 1967. Bruce, Steve. God is dead: secularization in the West. Oxford: Blackwell, 2002. Chilton, Paul. Analysing political discourse : theory and practise. London: Routledge, 2004. Davie, Grace. Religion in Britain since 1945: believing without belonging. Oxford: Blackwell, 1994. Durkheim, Émile. The elementary forms of religious life. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001. Fitzgerald, Timothy. Discourse on civility and barbarity a critical history of religion and related categories. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007. Francis, Matthew D. “Mapping the sacred: understanding the move to violence in religious and non religious groups”. PhD Dissertation, Leeds: University of Leeds, Forthcoming. Ignatieff, Michael. “Defenders of Rushdie tied up in knots.” The Observer. London, April 2, 1989. Karagiannis, Emmanuel. “Political Islam in Uzbekistan: Hizb ut-Tahrir al-Islami.” Europe-Asia Studies 58, no. 2 (2006): 261-280. Karagiannis, Emmanuel, and Clark McCauley. “Hizb ut-Tahrir al-Islami: evaluating the threat posed by a radical Islamic group that remains nonviolent.” Terrorism and Political Violence 18 (2006): 315-334. King, Richard. Orientalism and religion: postcolonial theory, India and “the Mystic East”. London: Routledge, 1999. Knott, Kim. The location of religion: a spatial analysis. London: Equinox, 2005. ———. “Theoretical and methodological resources for breaking open the secular and exploring the boundary between religion and non-religion.” In Keynote Lecture. Messina, Sicily, 2009. ———. “Theoretical and methodological resources for breaking open the secular and exploring the boundary between religion and non-religion.” Historia Religionum 2 (2010): 115-133. Knott, Kim, Alistair McFadyen, Seán McLoughlin, and Matthew Francis. The roots, practices and consequences of terrorism : a literature review of research in the Arts & Humanities. Leeds: University of Leeds, October 2006. http://www.leeds.ac.uk//trs/documents/University%20of%20Leeds%20terrorism%20lit%20re view%20for%20the%20HO.pdf. bin Laden, Osama. “Oath to America.” In The Al Qaeda Reader, edited by Raymond Ibrahim, 192195. New York: Doubleday, 2007. Malik, Kenan. “Exploding the fatwa myths.” guardian.co.uk, February 12, 2009. http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2009/feb/09/religion-islam-fatwa-khomeinirushdie. Department of Theology and Religious Studies University of Leeds, Leeds, LS2 9JT, UK iGov workshop on Islam and Religious Norms in the Public Sphere Martin, David. The religious and the secular: studies in secularization. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1969. ———. “The secularization issue: prospect and retrospect.” The British Journal of Sociology 42, no. 3 (1991): 465-474. Naumkin, Vitaly V. Radical Islam in Central Asia: between pen and rifle. The Soviet bloc and after. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2005. Rushdie, Salman. The satanic verses. London: Viking, 1988. Ruthven, Malise. A satanic affair: Salman Rushdie and the rage of Islam. London: Chatto & Windus, 1990. Stark, Rodney. “Atheism, faith, and the social scientific study of religion.” Journal of Contemporary Religion 14, no. 1 (1999): 41-62. Wallis, Roy, and Steve Bruce. “Secularization: the orthodox model.” In Religion and modernization: sociologists and historians debate the secularization thesis, edited by Steve Bruce, 8-30. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992. Warner, R. Stephen. “Work in progress toward a new paradigm for the sociological study of religion in the United States.” American Journal of Sociology 98, no. 5 (1993): 1044-1093. Webb, William L. “The Imam and the scribe.” The Guardian. London, February 17, 1989. Webster, Richard. A brief history of blasphemy: liberalism, censorship and “the satanic verses”. Southwold: Orwell, 1990. Department of Theology and Religious Studies University of Leeds, Leeds, LS2 9JT, UK