Bubb, S

advertisement

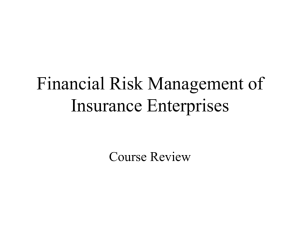

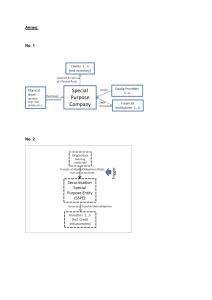

Asset Securitization is Too Big to Fail S.G. Badrinath Professor of Finance San Diego State University and S. Gubellini Assistant Professor of Finance San Diego State University First Draft May 2010 Please do not quote. ABSTRACT This paper explores the evolution and the current state of asset securitization. It begins with a brief review of securitization and how structured finance enabled the management of interest-rate and credit risks. It describes the role of credit default swaps in credit risk transfer. It documents the close historical relationship between securitization and various pieces of rule-making-FASB, Basel I and II, bankruptcy law, derivatives regulation and the role of rating agencies. It discusses the financial crisis from the perspective of the shadow banking system that emerged over the last few decades. It concludes with an assessment of the welfare implications of the various proposals for financial reform that are presently being contemplated. 2 1. Introduction Over the last 18 months, a tremendous amount of intellectual fire-power has been expended on attending to and then attempting to reform the Western financial system.1 Financial stability reports from central banks around the globe, reports from regulatory entities, IOSCO, FDIC, FASB, BIS, congressional inquiry commissions, and presidential reform agendas dominate the public policy space. One of the many concerns is the state of markets for asset securitization and the various practices by which interest rate and credit risk have been transferred through the global financial system. As Figure 1 shows large portions of this market have essentially stopped functioning since the Fall of 2008. During the intervening two years, this market has been kept on life-support by the FHA’s government backed programs and the US Federal Reserve purchases of nearly $1.25 trillion in mortgage backed securities. The latter program is scheduled to wind-down in the Spring of 2010. Market participants are understandably reluctant to enter into securitization arrangements without any clarity in terms of the legal, accounting and financial reforms that are being proposed. This paper surveys the landscape from a historical perspective and extracts lessons for both developed and developing markets alike. Media references to the financial crisis and its aftermath are focused on the failure of credit and accounting standards, of abusive practices by banks, investment banks, GSE’s, insurance companies and rating agencies. This court of public opinion simultaneously vilifies the roles played by these entities as well as the actions of those who came to their rescue and are now attempting to regulate them. In this telling, the common theme that emerges is one of excess, of testing and stretching the boundaries of prudent practice in adhering to credit standards, accounting conventions and legal constructions. What is rarely recognized in such forums is that securitization lies at the intersection of many evolving practices in the banking and financial 1 The financial crisis is often referred to as the sub-prime crisis, but the growth in sub-prime mortgage securitizations was mostly in the middle of the last decade and the performance failures in this asset class began in early 2007, well before the financial panic spread to other, ostensibly unconnected financial markets and securities. 3 system and that there has historically been a very direct connection between government policies, regulation and securitization. Accordingly, the paper commences by describing the evolution of securitization and its attempts to first manage interest rate risk and then subsequently credit risk. In this process the paper traces the development of CDOs and credit default swaps. It views securitization as the middle ground in a risk continuum that has bank lending with 100% risk retention at one end and 100% origination and distribution of loans at the other. The former extreme is exemplified by traditional banking where the lender holds the loan to maturity and manages the associated risks of default and interest rate changes. In the latter extreme, the lender only serves as an intermediary and private investors would absorb borrower and market risks in their entirety. In the middle, the lender retains a portion of the loan and securitizes the rest. With partial risk retention, intermediaries can signal the quality of the loan portfolio that is being securitized in the sense of Leland and Pyle (1977).2 The extent of this retention is masked by the complexity of the underlying instruments, the certification role of the rating agencies, the reluctance to regulate and the opaqueness of over-the-counter locations where many of these transactions are conducted. The paper continues to describe the benefits of securitization by examining the economic interests of consumers, lenders, and banks. It then addresses the growth of the shadow banking system and describes the causes for the recent financial panic. Next, the paper examines the centrality of securitization activities in the web of regulations and guidelines that have evolved over the last several decades. It highlights the tensions between securitization and FASB accounting standards, the bankruptcy code, the Basel Accords, credit derivative reform and the role of the rating agencies. As becomes evident, several of the rules devised by various institutions-FASB, FDIC, the Treasury, the SEC, the CFTC, Bankruptcy Law, and the Basel Accords- have their origins in periodic attempts to rein in extreme lending practices while attempting to preserve the essence of securitizations. 2 A recent proposal by the SEC suggests risk retention by requiring that the sponsor retain 5% of each tranche of ABS securitizations. This distorts the quality signal that ownership of the most risky tranche would send. 4 The consequences of a multi-decade thrust towards deregulation become evident along with the hubris in the power of market solutions and the innovations that accompany them. The general thrust of the reform proposals from the same rule-making agencies echoes similar sentiments. The piecemeal solutions to improve transparency, reduce excessive risk taking and complexity that are being proposed for the various affected parts of the financial system also raise some concerns about regulatory fragmentation. Still, informed market participants and regulators are working very hard behind the scenes to make the markets for asset securitization regain some semblance of normalcy. In other words, securitization is perceived as too big to fail. At the most basic level though, the ability to repackage cash flows and make them appear less risky is a market imperfection and the profits from exploiting that imperfection has become a social cost. The obvious benefits are home ownership, easy access to credit for borrowers, and an arguably lower cost at which banks are able carry out lending activities. To us it seems vital that such a cost-benefit analysis and how it generates welfare gains be central to any and all discussions of the political economy of securitization. The rest of the paper is as follows. Section 2 describes the various aspects of securitization. Section 3 briefly reviews the events in financial markets and the bailout of shadow banking over the past three years. Section 4 discusses the historical importance of regulatory trends in supporting securitization activities and the efforts at financial reform. Section 5 discusses alternative approaches and welfare implications and Section 6 concludes. 2. The characteristics of securitization. In its most elementary form, securitization refers to the process by which illiquid individual claims (loans) originated by financial institutions are transformed into securities and distributed to investors. While most of the media coverage addresses the fallout from commercial and residential real estate mortgages, the affected securitizations also involve loans, bonds, and a wide range of receivables and other cash-flow generating financial assets. However, the mortgage provides a useful starting point for describing and understanding the securitization process. Imagine a continuum, at one end of which loan funding remains essentially a primary market activity. Traditional thrift institutions would originate the loan, service the loan, fund it 5 with deposits and assume the associated interest rate risk as well as the risk of default of the individual borrower.3 At the other conceptual extreme, is a scenario where all the interest rate and credit risk is distributed in the secondary market to investors. In such a situation, there is no informational asymmetry as the lender does not have a stake in the quality of the loan. On this risk continuum, securitization occupies a middle ground where loans are bundled, risk is unbundled, and some of it is retained, with the entire structure being closely monitored. There is a three-step process. First, originated loans are pooled together into mortgage-backed securities enabling a diversification of borrower risk. Second, these assets are transferred in a true-sale to a special purpose vehicle (SPV) so that the cash flows from these assets cannot be attached in the event of originator bankruptcy.4 Third, the SPV issues different tranches or slices of bonds where the cash flow is passed through from the original mortgages comprising the pool according to different rules of priority. Typically, the senior and the largest tranches are paid first and bear the least risk. The lowest or equity tranche is the first to be affected by default in the underlying collateral pool. In this manner, securitization provides access to funding sources from secondary capital markets. As the structures are designed by the SPV, an iterative process with rating agencies is used to determine the type of credit rating that the different tranches can garner. The SPV engages an asset manager to trade the assets in the pool, a guarantor to provide credit guarantees on the performance of that pool, a servicer to process the cash flows generated from the pool and transferring them to the owners of the tranches and a trustee to oversee the activities of the SPV. Figure 2 provides a pictorial representation of the entire process. As comfort with securitization products and structures grew, numerous variations emerged over the years. In addition to the usual individual fixed-rate and adjustable-rate mortgages and mortgage backed securities (MBS), the assets pooled into the securitization began to include One of the primary reasons for the Savings and Loan Crisis of the 1980’s was the funding mismatches caused by borrowing short (via deposits) and lending long (to 30-year fixed rate mortgages). In addition to maturity mismatches, the Regulation Q ceiling on interest payable to depositors was kept artificially low, causing them to move to alternative interest bearing investments such as money market funds. 3 4 These entities have been variously described as special purpose entities (SPE), structured investment vehicles (SIV), or Asset Backed Commercial Paper (ABCP) conduits. While there are differences in the way the different entities operate, their common feature is that they all are bankruptcy remote. 6 loans and leveraged loans, high-yield corporate bonds as well as asset-backed securities (ABS). Thus the early collateralized mortgage backed obligation (CMO), were augmented by collateralized loan obligations (CLO), then by collateralized bond obligations (CBO), and later their aggregated version- the collateralized debt obligation (CDO). Once the securitization infrastructure was in place at most banks, new product development even involved the resecuritization of the lower (and more risky) CDO tranches into CDO-squared structures. Demand from private investors seeking yield in an environment of low interest rates began to mean that every conceivable cash flow stream was prone to being securitized. 2.1 Securitization and interest rate risk. On the risk continuum described above, the S&L crisis can be viewed as failure of the traditional model of concentrating risk in one set of entities. Indeed, after that crisis, mortgage securitization received a significant impetus with the government sponsored enterprises (GSE’s) taking on a more increased role in the mortgage market.5 Home ownership has been a cornerstone of public policy in the US and the GSE’s mandate was to provide liquidity, stability and affordability to this market.6 The typical view of securitization is one where the GSE’s attempted to manage interest rate risk by selling tranched securities rather than issuing debt to finance their purchase. This was done by prioritizing the cash flows to the tranches. Some tranches received only interest or only principal. Others allocated fixed rate payments to a floating rate and an inverse floating rate tranche, with different exposures to interest rate risk. Still others had explicit planned payment schedules, similar to a sinking fund to reduce uncertainty in payment times caused by variation in the speed at which mortgages are pre-paid. 5 This was not however, the starting point for securitization. Goetzmann and Newman (2009) point to a complex real estate market in the 1920’s with arrangements resembling securitization well before the GSE’s were created. 6 This mission is conducted by holding mortgages and MBS as well as guaranteeing other MBS issues. Loans that meet underwriting and product standards are purchased from the lenders and then pooled and sold to investors as MBS. The GSE’s received a fee for guaranteeing the performance of these securities. Second, they held some of the loans they purchase from banks for portfolio investment. Some of the holdings in the investment portfolio were themselves MBS issued by private firms (many of which have been subprime). Funding for the former is obtained from investors and funding for the latter is obtained by issuing agency debt creating moral hazard problems. 7 However, as part of that mandate to promote home ownership, Fannie Mae initially issued its own debt and retained the interest rate risk rather than passing it through to investors. Typically, the debt issued to finance the mortgage acquisition was of a shorter duration than the mortgage that it finances. Declines in interest rates triggered refinancing by borrowers in fixed-rate mortgages. Although the mortgage gets prepaid, the financing must still pay off at the higher original rate causing a loss to Fannie Mae. If interest rates rise, the borrower retains the mortgage and Fannie Mae still bears the loss of having to refinance its loan at the new higher rate. This feature of mortgages is curiously referred to as negative convexity. The bank-like behavior of the GSE has inevitably resulted in the bank-like consequences of maturity mismatch that plagued the S&Ls. In response, the GSE’s initially increased the issuance of callable debt to counter the impact of interest rate changes and later to access the over-the-counter interest rate swap market to accomplish maturity transformation. Ironically, the SPV’s that were structured as ABCP conduits became subject to similar maturity mis-match problems in 2009 when money market funds lost confidence in the safety of that paper. 7 2.2 Securitization and credit risk. Credit risk was initially managed by the GSE’s by strictly adhering to loan size, conformity and underwriting standards. As the mortgage market expanded, the guarantee business became a larger part of GSE operations. Loans that were bundled and sold as MBS came with a guarantee that the unpaid balances to security holders on individual mortgage defaults would be paid by the GSE. The GSE would then attempt to recover that amount through the foreclosure process. Therefore, the security holder would not have any exposure to credit risk. The Collateralized Debt Obligation (CDO) became a common way in which credit risk was tranched to investors in much the same way that mortgage pre-payment risk was distributed in a CMO. Although it is often mistakenly described as a credit derivative, a CDO is essentially a multi-class bond where tranche investors receive cash flows from reference assets in a collateral 7 Kacperczyk and Schnabl (2009) document the characteristics of the asset-backed commercial paper during the financial crisis. 8 pool according to strict definitions of priority. Demand for securitized product from such investors is part of what contributed to the financial meltdown of recent years. As CDOs and other private lenders entered the securitization space, various types of credit enhancements began to proliferate.8 The quality of the collateral asset pool and concerns regarding adverse selection by pool originators resulted in several assurances, both internal and external.9 Internal guarantees include a cash reserve from setting aside a portion of the underwriting fee for creating the collateralized structure, or a portion of the interest received from the collateral assets, after paying interest on the tranches, or even by deliberate overcollateralization where the volume of collateral assets placed in the structure is greater than the volume of liabilities, thereby providing a layer of protection when some assets default. In addition to credit guarantees from the GSEs issuing the MBS, external guarantees were obtained from the sponsor and by the direct purchase of credit insurance from mono-line insurance companies or over-the-counter insurance through credit default swaps.10 2.3 Securitization and credit risk transfer-the credit derivatives market. The credit default swap (CDS) has emerged as the primary vehicle through which credit risk is transferred and traded.11 Simply stated, a CDS is a put option on credit risk.12 Buyers of protection from a credit event pay a periodic premium. If there is a relevant credit event that affects the value of the underlying asset, then the protection buyers are made whole by the 8 Credit enhancement is a wonderful euphemism for loss distribution. 9 If originators have the most information about the quality of the underlying financial claims then it is reasonable to expect adverse selection on their part, only keeping the good loans and selling the bad ones. In the extreme, loan quality will decline across the board as demand for loans from securitizers weakens the incentive for originators to screen the loans This leads to issues of information asymmetry causing rational lenders to demand a lemonspremium, Duffie (2007). 10 Understandably, the level of these credit-enhancements was critical to obtaining a favorable rating from the rating agencies. 11 Although other structures like the Total return swap (TRS) and the Credit-Linked Note (CLN) are also related vehicles, we confine our discussion to the CDS instrument in the interest of brevity. Contract terms and definitions of the credit event are standardized by the International Swap Dealer’s Association (ISDA). More details on the CDS are available at www.isda.org. 12 9 protection seller and in this fashion they have shed the credit risk. Sellers of protection assume the credit risk in exchange for that periodic premium income. The appeal of the CDS becomes clear when it is compared with corresponding bond market transactions. Exposure to credit risk can be achieved either by owning the bond or selling the CDS. Owning the bond requires capital and also creates interest rate risk exposure while selling the CDS only requires mark-to-market adjustments and periodic collateral. Likewise, being short credit risk implies being either short the bond or buying the CDS. Again, the former is difficult to do while the latter is easy. In both cases, the CDS offers leverage and liquidity and is thus an easy expression of a view on credit in a manner that has not been possible in the secondary bond market. This “insurance” product has received considerable notoriety in the media. First, the direct purchase of a CDS without owning the underlying credit is akin to a short sale.13 Second, owners of the underlying credit can purchase protection against its possible default- an application similar to that of a protective put option. 14 Third, from initially insuring the default risk of bonds, the CDS market soon rapidly expanded to include CDS products on loans, mortgagebacked and asset-backed securities. Portfolio versions of these known as basket CDS and index CDS products traded in the middle of the decade. The now notorious ABX and TABX indexes, are securities that take one or two deals from 20 different ABS programs, with 5 different rating classes-AAA, AA, AA, BBB, BBB-. The bottom two are further combined into the TABX which is the most sub-prime and experienced the most rapid declines in value at the beginning of the financial crisis.15 The synthetic CDO is a special purpose securitization vehicle that makes extensive use of the CDS instrument. The Bistro structure conceived initially by JPMorgan in 1997 became a Some commentators have urged that this use of a CDS is similar to taking out insurance on some one’s home and then burning it down to realize its value. The criticism here is not of the CDS instrument at all, but more an expression of discontent with the short selling in general. 13 Traditional forms of insurance incorporate the notion of “insurable” interest where the primary purchasers of insurance are those owners of assets who deem it necessary to seek protection against its loss of value. Restricting CDS purchases to this class of market participants is identical to only permitting protective put options to be traded and would thus limit the flexibility of market participants. 14 15 As an illustration, the ABX.HE.A-06-01 is an index of asset-backed (AB), home-equity loans (HE) assembled from ABS programs originating in the first half of 2006. 10 template by which the cash flows to tranches of securitizations were generated from the premiums received by selling credit default swaps on a portfolio of underlying securitizable assets. In other words, instead of a pool of assets generating cash flows, the insurance premium representing their likelihood of default is itself distributed directly to the tranches. Since the rate of default in the pool of underlying assets governs the amount of the premium that will be received from credit default swaps sold on those assets, this amounts to essentially the same bet.16 2.4 The appeal of securitization. For investors, the appeal of securitization structures is that in normal times, there is a diverse pool of mortgages and loans which are low in correlation so that in the event of a default, the senior tranches will continue to be paid out from the cash flows that are not lost in that default. For borrowers, the appeal of securitization is that it makes credit more easily available and at better terms.17 For banks and financial institutions that originate these loans, the securitization is viewed as providing a lower cost method of funding than the typical secured lending activity that they have historically engaged in. However, Hansel and Krahnen (2007) find that CDO securitizations actually increase the risk appetites of sponsoring banks when the equity tranche is retained. Gorton and Souleles (2005) argue that the insulation of the SPV from the bankruptcy of the sponsor acts to reduce bank bankruptcy costs and is especially relevant for sponsoring banks that have large risks of bankruptcy. With hindsight, the implicit government guarantee embodied in “too big to fail” makes this argument somewhat redundant. 3. Securitization, bank runs and the bailout of shadow banking. The charges filed by the SEC in April 2010 against Goldman’s Sachs pertain to their lack of disclosure of information while such a synthetic structure was being created. 16 17 In a study sponsored by the American Securitization Forum, Sabry and Okongwu (2009) document that a 10 percent increase in securitization activity resulted in decrease of between 4 and 64 basis points on yield spreads, depending on the specific type of the loan. Moreover, a 10 percent increase in secondary market purchases (of loans) increases mortgage loans per capita by 6.43 percent. 11 Critics of securitization (Levitin, Pavlov and Wachter, 2009) argue that the securitization process was corrupted by the emergence of a shadow banking system in the late 1990s. These shadow banks are mortgage real estate investment trusts, insurance companies, private equity funds, the, money market funds, mutual funds, pension funds and hedge funds. Investment dollars from many of these entities served as the “deposits” that the special purpose vehicles, CDOs and the housing GSE’s employed to fund securitizations. Gorton (2009) argues that this shadow banking system is really the culmination of several decades of deregulation that facilitated the integration of the traditional banking system with capital markets. By some measures about 60% of the credit system is facilitated by shadow banking (Date and Konczal, 2010). Indeed, commercial banks had little choice but to compete in this arena, since holding loans and funding them with deposits was not a profitable business for them anymore.18 The financial crisis of the last few years involved a series of runs on this shadow banking system. This was first visible in the asset-back commercial paper (ABCP) market and then in the repurchase market where institutions obtained short-term financing. The behavior of two key spreads serves to illustrate the extent of the run on the shadow banks. The first is the 30-day A2/P2 and AA commercial paper spread which widened to 600 basis points in November 2008 from an average of 10 basis points in quieter times.19 The second is the option-adjusted spread on the Merrill Lynch AAA Master Asset Backed Securities index which widened from a normal range of 100-150 to 750 basis points at about the same time.20 Next the failure of the GSE’s made their implicit government guarantees explicit. The subsequent collapse of AIG whose aggressive selling of CDS insurance required a federal bailout, was another significant event in this crisis. The response of the central banks to this ongoing crisis was coordinated and strong. The European Central Bank, The Bank of England, Her Majesty’s Treasury, the U.S Federal Reserve, 18 This was one of the motivations behind the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act of 1999, which relaxed the separation of commercial and investment banking activities that were enshrined in the Depression Era Glass-Steagall Act. A2/P2 Commercial Paper refers to programs that garner at least one short-term credit rating of “2” but noe below it. AA are programs rated “1” or a “1+” but none below. 19 20 International Monetary Fund, Global Financial Stability Report, 2009. 12 The U.S Department of the Treasury initiated several programs whose purpose was to “bail-out” the shadow banks. Outright purchases of secured commercial paper and GSE obligations, the acceptance of securitized paper as collateral, the provision of liquidity facilities, capital and financing to private entities to purchase CMBS and private RMBS as well as non-mortgage MBS via the PPIP, TALF and TARP programs were some of the steps taken during the Fall of 2008 and Spring of 2009. The thinking behind these bailouts is that the Federal Reserve was better able to hold these assets either until maturity or until some point where the housing market recovered. The GSE’s are still requesting supplemental funds and thus far proposals for financial reform do not address their situation. This socialization of debt with all its welfare implications continues to this day with the recent events surrounding the PIIGS countries in Europe. One common theme underlying this shadow banking system was the lack of transparency from and regulation of several of these pools of capital. Infrequent and limited disclosure is a common feature in the practices of hedge funds, private equity funds and in the over-the-counter credit derivatives markets where much of structured credit finance operated. The opacity is often justified because of the illiquid nature of many of the holdings of these assets, but deterioration in their values in extreme situations is very hard to track down. To address complexity and transparency, the Treasury Office of Domestic Finance floated two proposals. The first was the MLEC Super SIV where the illiquid holdings of banks would be pooled together and held until a better time to liquidate them rather than to dispose them at the panic-induced fire-sale prices in the market at that time (Swagel, 2009). However, in the mindset of deregulation, the innovative activities of these entities were generally regarded as providing liquidity and efficiency to financial markets. The hope was that the reputational capital of the participating institutions would constitute an effective deterrent to excessive and abusive practices. With hindsight, it is easy to recognize that one implication of the diversification benefits that securitization provides to the senior and super-senior tranches is that it makes them effectively short correlation. Additionally, mortgage products are well known to exhibit negative convexity or concavity. Negative convexity essentially implies that they lose value when interest rates fall, partly because the rush of borrowers to refinance reduces the duration of the bonds. With correlated defaults, this effect becomes even more severe. At times of financial crisis, all 13 correlations tend towards to unity, and it should not be surprising that these tranches that were rated as “safe” were adversely impaired.21 4. Reforming Securitization. Reinhard and Rogoff (2009) find that systemic banking crises are typically preceded by credit booms and asset price bubbles, with significant drops in housing prices, equity prices and output and significant increases in unemployment and central government debt. In a comforting note, they state that these major episodes are sufficiently far apart in calendar time for policymakers and investors to believe that “this time is different.” Indeed, in recent crises like the S&L case, the same issues of moral hazard, asymmetric information and systemic risk were discussed. This section examines the implications of the banking crises from the perspective of securitization and addressing its intersection with accounting practices, bankruptcy law, ratings agencies, banking regulation and credit markets. 4.1 Securitization and Accounting Principles. Several guidelines from the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) have sequentially had direct relevance for asset securitizations. A brief history of the Boards standards in this regard reveal clearly the rearguard action that the Board performs in attempting to thwart transgression. The first, titled Accounting for Transfers and Servicing of Financial Assets and Extinguishments of Liabilities, was issued as FAS 125 in 1996 and has now been completed superseded. In its 1996 incarnation, FAS 125 articulated that a transfer of assets constituted a sale if :a) the assets were insulated from sponsor bankruptcy; b) the transferee or a qualified special purpose entity (QSPE) can pledge or exchange those assets and c) the transferor does not maintain effective control over those assets. In April 2001, FAS 125 was modified as FAS 140 and clarified the implications of asset transfers during securitization by unequivocally spelling out that the assets and liabilities of a QSPE do not get consolidated with the financial statements of the transferor. It also suggested newer disclosure rules for transactions and advocated stress tests. 21 The assumptions regarding default and correlation in the models used by rating agencies did not anticipate this outcome resulting in a rash of severe ratings downgrades once the effect was noticed. 14 In 2003, after Enron’s abuse of FAS 125/140, FASB Interpretation No. 46(R), Consolidation of Variable Interest Entities was issued to further clarify when consolidation rules applied. Prior to this rule, the consolidation of SPE financial statements with those of the sponsor was required when the sponsor had a controlling financial interest, which in turn was broadly measured by majority voting rights. FASB 46® expanded the definition of the sponsor and of controlling interest. The financials of entities classified as Variable Interest Entities (VIE) must be consolidated with those of the primary beneficiary. The primary beneficiary is defined as the organization that absorbs the majority of the VIE’s expected losses. Sponsors who typically offer liquidity and default guarantees are deemed primary beneficiaries. Controlling interest of equity investors in the SPE is measured by their right to residual returns and their obligation to absorb losses in addition to majority voting rights.22 The latest incarnation of FAS 125/140 now known as FAS 166 was released in June 2009 in response to the recent financial crisis. It requires more information about transfers of financial assets, including securitization transactions, and where companies have continuing exposure to the risks related to those transfers. Specifically, it requires that the transferor of assets consider whether the transferee would be consolidated by the transferor, It eliminates the concept of a “qualifying special-purpose entity,” first recognized in FAS 140 which permitted nonconsolidation of financial statements in certain situations. It changes the requirements for derecognizing financial assets, and requires additional disclosures to aid transparency about transfers of financial assets and a sponsor’s continuing involvement in them. Statement 167 is a revision to FASB Interpretation No. 46(R), Consolidation of Variable Interest Entities. FAS 167 strengthens the guidelines in FAS -46R by making consolidation more directly linked to the entity’s purpose and design and a sponsor’s ability to direct the activities of the entity that most significantly impact the entity’s economic performance. Taken together, 22 Bens and Monihan (2007) report some reduction in ABCP issuance pursuant to application of the consolidation rules applying to VIEs. To avoid this consolidation, financial institutions came up with a restructuring called an expected loss note. Third party investors in this note take an equity position in the conduit and agree to absorb a majority of the first loss portion. One can think of this note as a “consolidation” derivative and the reason for its creation appears to have been to get around FASB regulations requiring consolidation. 15 these standards are another attempt to clarify the extent of originator liability in these transactions. These efforts by FASB bring US GAAP accounting more in line with international (IFRS) standards. However, these stricter rules have caused ratings agencies to express the view that senior tranches of asset securitizations are “unlikely” to receive AAA ratings. The Treasury and the Obama administration have lent their support to originator risk retention arguing that originators should have some “skin in the game.23 The idea of 5% risk retention by originators appears in various versions of Congressional reform proposals. The concern is that, if implemented, this rule could limit off-balance sheet securitizations. 4.2 Securitization and Bankruptcy. What is also not commonly understood is the extent to which securitization has stood in tension with the bankruptcy code. In a straightforward lending arrangement, secured creditors have an incentive to monitor the firm and to conduct due diligence on an ongoing basis, in order to prevent liquidation. In contrast, with a securitization, the assets are turned over to the SPV in a “true-sale.” True-sale implies that the sponsor sells the assets to the securitizer as an off-balance sheet transaction, is free from monitoring the assets for performance and no longer carries them on the books. If met, the true-sale standard implies that cash flows from the underlying assets cannot be attached in any originator bankruptcy proceeding since they have been “sold.” In this sense, the securitized assets are said to be bankruptcy-remote and this distance from the originator is central in marketing the securitized assets to investors.24 23 Indeed shortly after the financial crisis started, several banks made public proclamations of their intentions to take several of the offending off-balance sheet entities back on their balance sheets. 24 In 2001, the LTV Steel Company, Inc. challenged its pre-bankruptcy securitization facilities, arguing that the transfers to the SPVs were not true sales and, therefore, that LTV should be able to use the collections of receivables as "cash collateral” by giving adequate protection under bankruptcy law. LTV’s rationale was that, without such use, it might have to cease its operations, thereby jeopardizing employee jobs and retiree benefits and adversely affecting the local economy. The bankruptcy court permitted LTV to use these collections pending resolution of the true sale issue. However, no legal precedent was established as the parties reached a settlement. 16 This true-sale is supported by a legal opinion that is not always clear and unambiguous, but very carefully reasoned and buttressed as available by citations from both common-law and case-law. Issues regarding the type of bankruptcy that the originator may become subject to as well as any relationships between the two parties are usually spelled out. Many early securitizations before 2000 used two sets of special purpose entities to accomplish bankruptcy-remoteness. This opinion frequently runs 40-50 pages and essentially passes the buck to a rating agency which makes a judgment that the opinion is strong enough to consider the transfer of securitized assets to an SPV as a true-sale so that the resulting tranche structures are deemed worthy of a high credit rating. In 2000, the FDIC clarified the “securitization rule” codified as 12 C.F.R. 360.6 which essentially was a statement that the FDIC would not use its statutory authority to repudiate “truesale” contracts entered into during a securitization as long as GAAP principles were met. This clarification lent further support to the bankruptcy-remote character of securitized assets in the event of sponsor bankruptcy. In 2005, the Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act explicitly amended Section 541 of the Bankruptcy code to exclude assets transferred in an asset-backed securitization from the debtor’s estate, thus providing a “safe harbor” for securitization activities.25 While this represented a victory for securitization advocates, the financial crisis of 2007-09 has created a cloud of uncertainty. GAAP modifications in 2009 subsequent to the current financial crisis make securitizations via a truesale less likely. In March 2010, the FDIC introduced an extension to the 2000 securitization rule until September 2010 essentially grandfathering securitizations that commenced before these new GAAP standards were defined. 4.3 Securitization and the Basel Accords. In the bankruptcy code, the eligible asset-backed securities are referred to as those where “at least one class or tranche of which was rated investment grade by one or more nationally recognized rating organizations when the securities were initially issued by an issuer.” Once again the rating agencies have been granted significant powers. 25 17 The evolution of minimum capital standards for banks, proposed in the various Basel accords were an attempt to globally regulate risk taking in the banking industry. 26 Basel I had overly broad risk categories and did not tie regulatory capital charges to economic risk. Under Basel II, banks with deposits of over $250 billion had more stringent requirements which were optional for the smaller banks. According to Hancock et al. (2005), Basel II capital requirements for GSE securitized mortgages was actually lower than for loans originated by banks. The differential regulatory criteria for different banks created an incentive for regulatory capital arbitrage whereby such banks have “an incentive to sell the credit risk on loans whose regulatory capital exceeds their economic capital to institutions not bound by the same capital regulations, and also to hold the credit risk on loans whose regulatory capital is below their economic capital.” Furthermore, the regulatory capital requirements gave considerable importance to the role of credit ratings. Capital charges were set at 8% and risk-weighted based on long-term credit ratings with weights ranging from 20% for AAA ratings to 350% for BB ratings. This implied that a $100 million loan would require $1.6 million in capital if it was rated AAA and $28 million in capital if the loan was rated BB. However, with the purchase of a CDS, a BB rated security could be transformed into a AAA rated one.27 Furthermore, capital requirements carry a zero-risk weight for CP funding. Bake et al. (2010) document recent modifications to the Basel II capital requirements regime in response to the financial crisis. These include a treatment of resecuritization exposures designed to treat CDO structures, better stress testing, a value-at-risk framework and other operating constraints. 4.4 Securitization and the role of ratings agencies. The centrality of rating agencies in the Basel II protocols, in the bankruptcy code and in the western public consciousness is undisputable. In its final report in July 2009, two of the five recommendations of the US Dept of the Treasury on reforming asset securitizations pertain to 26 Ironically, Basel I was initiated by the US Federal Reserve and the Bank of England, prompted in part by complaints from domestic banks about undercapitalized foreign banks operating on their turf. 27 The poster child for this activity was AIG and a quote from their 2007 10-K report states clearly that they sold CDS protection to European banks, “…. for the purpose of providing them with regulatory capital relief rather than risk mitigation in exchange for a minimum guaranteed fee”. 18 strengthening the performance of credit rating agencies and reducing over-reliance on these ratings. This section provides a discussion of their role and critically examines various proposals that have been put forward. Rating agencies are closely involved in structured credit finance at many levels. First, they evaluate the credit risk of the assets being pooled and offered as collateral. Second, they review the structure, examining the tranches and credit enhancements. The fees levied for these structured finance ratings accounted for over 40% of the revenues for Moody’s and Fitch and grew at about 30% annually. The feedback loop between the originators of the deal and its raters has again raised questions about conflict of interest28. Moreover, these pre-rating criteria are not shared with investors. Third, they investigate the legal status of the SPE operating the securitization. Fourth, they evaluate all parties to the transaction—the originators, servicers and the quality, skill and experience of the asset managers. Two defenses are commonly offered in support of rating activities. The first is that ratings are long–term opinions which are intended to reflect expected asset performance over a business cycle, and not intended to capture shorter-term market volatility. Recent agency downgrades of credit products belie that assertion. These downgrades have been across all rating classes and extremely severe with existing ratings being taken down multiple levels. Understandably, these have been responses to the public outcry to which the raters have been subjected. Nevertheless, the transition to a short-horizon rating undermines an already beleaguered process. The second is that the complexity of the structures and transactions being rated requires caution in interpretation. In that case, one would expect to see ratings that are better distributed around the mean and also ratings that differ across the agencies29. What one observes is an upward bias, suggesting flaws in their incentive structure. 28 The role played by rating agencies has two close precedents from recent financial history. These are the questions of auditor independence following the Enron and WorldCom accounting scandals and the role of financial analyst recommendations during the technology bubble of the late 1990s. The former resulted in Sarbanes-Oxley. 29 Drucker and Puri (2006) find that covenants are more restrictive when the views of rating agencies differ. 19 Despite these criticisms, it is important to recognize that there will always be consumers for opinions that rating agencies currently provide. New products will develop in financial markets and will be more complex. Some subset of market participants will call for and benefit from certifications for asset quality, credit worthiness and credit risk in evaluating the suitability of an investment. Regulators can either work with the rating agencies or become a rater themselves. Accordingly, several solutions to maintain the arms-length nature of raters have been proposed. The first is to remove barriers to entry in the ratings market- a step taken in the enactment of the Credit Rating Agency Reform of Act of 2006. Prior to this, it was not uncommon for prospective entrants to engage in risky business practices30. A second is to make potential purchasers of the rated product pay for ratings rather than its sellers. However, the buy side is equally likely to influence the ratings process as the sell side. It is not hard to imagine a large institutional holder exerting pressure for favorable ratings on the securities they hold. Making investors pay is also likely to cause free-rider problems that reduce the incentive for research that generates quality ratings in the first place31. A third is “to leave it to the market.” Models that use market prices to extract default probabilities are very appealing but that presumes the existence of liquid secondary markets for the underlying asset or some proxy of it that permits price discovery. Credit derivative products are not close substitutes and the market price of a CDO tranche, when it trades, may not shed much light on the likelihood of default of another. Nevertheless, stale prices may be better than no prices at all. A fourth is to hold the agencies legally liable and/or accountable for their ratings. A fifth argues that more disclosure of the processes used by the rating agencies would enable investors to better evaluate their purchases. Raters should describe the products that are being rated, the criteria used for rating and acknowledge the shortcomings in their models32. A sixth proposal that is gaining some traction is an amalgam of the issuer pays model that addresses some of the problems with conflict of interest and competition. An issuer 30 Dominion Bank Rating Services (DBRS), a Canadian rating agency took 13 years to break into the US ratings market. As part of this process, they rated ABCP trusts in Canada and elsewhere, a rating that the big three, S&P, Moody’s and Fitch declined to provide. 31 Raters do appear to be aware of this possibility and address it by providing free access to some information. 32 See the October 2007 issue of the Financial Stability Report from the Bank of England. 20 desirous of a rating would pay the fee to a regulator (rather than directly to the rating agency) and the regulator would then assign one of several rating agencies to make the determination of credit quality. The choice of rating agency could be random or depend upon the complexity of the transaction and the rater’s ability to deal with that complexity. Regardless of the eventual outcome of these considerations, it is important to recognize that concerns about rating agency involvement were also raised during past financial disruptions. Conflicts of interest among financial intermediaries are a necessary consequence of business and will continue to pose challenges for the management of resultant financial and reputational risks. These should be considered carefully in creating an environment for due diligence by investors. 4.5. Securitization and the regulation of derivative contracts. The reluctance to regulate is visible most clearly in the history of derivatives regulation. Whether to permit off-exchange activity and how to regulate on-exchange activity has been a pressing concern throughout this history. Since credit securitizations are so closely linked with derivatives, this section first provides a brief post-Depression overview. 4.5.1 Regulation prior to 2000. Regulation of exchange-traded futures contracts on agricultural commodities was the purview of the Commodity Exchange Act (CEA) of 1936.33 Under the Commodity and Futures Trading Commission Act of 1974, the CFTC became the new regulator whose role was expanded to include all exchange-traded futures contracts including financial futures. Off-exchange futurestype transactions could be deemed illegal. The adoption of a proposal from the U.S Treasury, called the Treasury Amendment, resulted in the exclusion of forward contracts such as those in foreign currency markets from regulatory supervision by the CFTC. 34 33 The primary motivation purpose behind this regulation was to dampen price volatility by monitoring speculator ability to manipulate prices. 34 The thinking, summarized nicely in a speech by Federal Reserve Chairman Greenspan in 1997, was that foreign currency markets were different from agricultural markets in that they were deep and difficult to manipulate. Therefore regulating them was “unnecessary and potentially harmful.” 21 The subsequent rapid growth of interest rate swaps in the 1980’s gave rise to renewed concerns about the CFTC’s ability to ban over-the-counter activity in these instruments. This issue of legal certainty persisted despite several soothing statutory interpretations from the CFTC. A provision in the Futures Practices Act of 1992 eventually granted the CFTC the right to exempt offexchange transactions between “appropriate persons” from the exchange-trading requirement of the CEA. This right was almost immediately exercised in the context of interest-rate swaps. Concerns about the interest-rate swap market still continued amidst turf battles in 1997-98 between the SEC and CFTC on how to regulate the broker-dealer firms in this market. A Presidential Working Group was formed comprising the Chairman of the Federal Reserve, the Chairpersons of the CFTC and the SEC and the Treasury Secretary. At this time, events pertaining to Long Term Capital Management (LTCM) and their leverage in the OTC derivatives markets came to light. After multiple hearings and a bailout of LTCM orchestrated by the Federal Reserve, the Commodity Futures Modernization Act of 2000 was signed into law.35 4.5.2 The Commodity Futures Modernization Act (CFMA) of 2000. It is well known that under the CFMA, over-the-counter derivative transactions between “sophisticated parties” would not be regulated as “futures” under the Commodity Exchange Act (CEA) of 1934 or as “securities” under the federal securities laws. This fragmented regulation implied instead that banks and securities firms who are the major dealers in these products would instead be supervised under the “safety and soundness” standards of banking law. A new Section 2(h) of the CEA created the so-called Enron “loophole” that excluded oil and other energy derivatives from CEA requirements of exchange trading. In addition, Title 1 of the CFMA specifically excluded financial derivatives on any index tied to a credit risk measure. The Act provided even further impetus for credit derivatives markets to engage in risk transfer activities pursuant to securitization. A 2009 documentary on Frontline titled “The Warning” describes the 1997-98 conflicts between Brooksley Born, the Chairwoman of the CFTC and the other members of the Presidents Working Group. The former was in strongly in favor of regulating OTC derivatives but the other members, who were opposed to any regulation, prevailed. 35 22 In August 2009, after the financial crisis and the collapse of securitization, regulation took a 180degree turn when the US Treasury proposed legislation that essentially repeals many of the CEA exemptions above and argues for an exchange-traded credit derivatives market. 4.5.3 Fostering an exchange-traded credit derivatives market. The complexity and opacity of over-the-counter credit derivatives markets and their purported role in several scandals in the headlines makes them obvious candidates for financial reform agendas. One possible solution with multiple adherents that is currently making its way through Congress borrows from the Commodity Exchange Act of 1936 which required that futures and options trade on organized exchanges. The goal is to encourage the development of exchangetraded derivatives markets for credit. Exchanges have already created templates for and are making markets in trading credit products. Credit futures commenced activity in March 2007 with a Eurex credit futures contract. Plans are under way for NYSE-Euronext to created standardized CDS contracts to facilitate exchange trading. In June 2007, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) launched its Credit Index Event contract which is a fixed recovery CDS product36. Since 2009, the CME offers clearing-only services for over-the-counter CDS products along with several founding members.37 The obvious motivations for the exchanges are to profit from the volume of activity in these markets. Currency derivatives markets also started over-the-counter and now trade in parallel on an exchange platform and also provide some support for this recommendation. Making credit derivatives exchange-traded has several advantages. First, by interposing itself between the buyer and the seller, the clearing-house reduces counterparty risk. As an independent entity, the clearing-house is also separate from the counterparties, unlike over-thecounter settings, where presently, investment and commercial banks make a market as well as 36 Since the CDX and iTraxx products described in 3.3.5 above are branded, the CME has created its own index of underlying reference entities. 37 See CME Group Launches Credit Default Swap Initiative; Begins Clearing Trades, Chicago-PRNewswire-First Call, Dec 15, 2009. 23 take on credit risk exposure. Second, clearing-houses are generally well capitalized and their credit-worthiness is less likely to be called into question. Third, exchange trading makes it possible to view market prices clearly. If the underlying securities are complex and hard to value, then market activity may be light and prices may be stale, but that may be still be preferable to having no prices at all. Fourth, exchanges impose a settlement or a mark-to-market reconciliation of the exposures of the two parties on a daily basis. In contrast, mark-to-market practices in OTC derivatives are less frequent and likely to be more contaminated. For instance, hedge funds often carry leveraged positions at cost. Some OTC desks keep the books on an “accrual” basis 38. A disposition effect comes into play and losses are “accrued” while gains are marked-to-market immediately. Fifth, the contracts can be standardized, along the lines of the ISDA, but incorporating default events that may be unique to the legal environment in the local market. Finally, such an exchange-traded credit derivative market is more likely to preserve the benefits of securitization along with a much-needed increase in transparency and an observation of market prices. Indeed it is the last feature that appears to be the sticking point as traders are reluctant to forego past practices. It should also be noted that crises can and have happened in exchange traded markets as well. 5. Towards more effective regulation. Recurring concerns about asymmetric information and systemic risk have always caused society to fret about banking regulation. Its effectiveness is even more critical in this new world of mass-produced structured finance technology, credit risk transfer, ratings dependence and hedge funds. As documented above, this complexity is also reflected in the accounting and regulatory standards required for effective oversight with rules for determining controlling financial interest, and Basel II guidelines for determining capital requirements becoming extremely detailed. Events of the past few years provide the most comprehensive evidence to date that many of these rules were a day late and several dollars short. 5.1 The Covered Bond Alternative 38 Anecdotal evidence suggests that, at times, mark-to-market practices are postponed if the transactions will not be unwound until expiration. 24 In Europe, structures similar to securitizations have increasingly been conducted using “covered” bonds, from thePfandbrief in Germany, the Obligations Foncieres in France and the Cédulas Hipotecaria in Spain. Simply stated, holders of covered bonds have a preferential claim on the collateral assets in the event of default of the originator. The claim is supported by a legal regime created specifically for this purpose. Assets are maintained in separate, easily identifiable pools and remain on the balance sheet of the issuer. Exposure to credit risk is retained with the issuer, thereby aligning the incentives of the issuer and the investor. While in principle, the covered bond alternative holds some promise, the escalating situation of government debt in the PIIGS countries does not provide any solace for this alternative. 5.2. Principles-Based Regulation. In general, rules enable a checklist mentality towards monitoring compliance and enforcement, with frequent revisions to existing guidelines and interpretations of current guidelines creating a vicious cycle. Market participants detect loopholes in existing laws and devise innovative methods to exploit them39. Regulators step in to remove these loopholes and in the process, inadvertently create new ones. Indeed it is the very nature of regulation that regulators have to play catch-up to those they seek to regulate. As Caprio et al. (2007) point out, the profitmaximization incentive of regulatees will create rapid and creative responses to earlier regulatory proclamations. In recognition of these dynamics, regulatory agencies in both the UK and Canada have begun to move towards principles-based or “light-touch” regulation. In this approach, broad principles of governance are articulated, rather than an attempt at micromanagement. The common example that is used to illustrate the difference in these two approaches is with reference to how driving conduct is regulated. A rules-based approach would state a speed limit of 65 mph and a traffic officer would issue speeding tickets if a driver was in 39 In 2002, J.P.Morgan won three awards for innovation from Risk Magazine-Derivative House of the Year, Interest Rate Derivatives House of the Year and Credit Derivatives House of the Year. The contributions cited include a description of a “FASB-busting” solution to hedge anticipated changes to foreign currency income. 25 violation of that rule. A principles-based approach would merely state that a driver would drive in a manner that was reasonable and prudent under the circumstances. In the latter context, factors such as time-of-day, road, traffic and weather conditions, as well as the experience of the driver would go towards determining prudent conduct. At a legislative level, the goal is one of promoting prudent driving practices while a lower level works out the details of how those practices would be implemented.40 In a sense, this is a form of enforced self-regulation. Most descriptions of principle-based regulation make it appear as if it is the polar opposite of rules-based regulation. While this may be the correct view if one takes Sarbanes-Oxley as the epitome of rule making, there is no reason why the two cannot exist at the same time. In the US, practices that adhere to the Prudent Man Rule and the Business Judgment rule are largely principles-based. Even in the area of securities regulation, the SEC’s approach relies more on rules while the CFTC leans towards principles. Furthermore, principles may be more appropriate for certain types of business but not other types. However, regulator behavior in a principles-based setting can also become arbitrary and create a tendency to go after entities with deep pockets. Nevertheless, the promise of a principle-based framework is that it may be less likely to cause mis-directed innovative activity and let it proceed relatively unhampered.41 5.3 Welfare implications. Activities of the welfare state are usually taken to imply government spending that supports education, health, pensions, unemployment and providing social safety nets for citizens of advanced economies. As the paper documents, securitization activities in the US have been driven by social policies that include broadening homeownership and easing the credit available to citizens. In addition, some have argued that the ability of banks to securitize a large portion of their loans has resulted in lowering their cost of funds. Securitization’s ability to repackage cash flows and make them appear less risky is, at one level, a market imperfection and the attendant 40 In 2001, the Financial Services Authority (FSA) in the UK developed a set of 11 high level Principles of Business that it uses extensively. 41 The SIFMA, the CME group and Treasury Secretary Paulson were all early supporters of some form of principlebased regulation to deal with the financial crisis. 26 gains to arbitrage from exploiting them is one of the costs. A larger cost is the government guarantee to the GSE’s that resulted in their conservatorship in 2008 and the eventual bailout of the shadow banks. Moral hazard arguments would suggest that these implicit guarantees actually increased risk taking behavior. Even if we grant that some of these costs are/were acceptable in normal times, the inescapable fact is that the “abnormal” collapse of securitization and the subsequent bailout of the many associated financial institutions resulted in the socialization of these costs with the potential for their transfer to future generations.42 Simply stated, the issue is really whether the government should be so closely involved in programs designed to broaden homeownership and access to credit for its citizens. However, the complexity of the transactions in a securitization has effectively meant that a broader social conversation of the tradeoffs from securitization can hardly take place in the public sphere. The inexorable growth of innovation implies that a return to a simpler regime is highly unlikely. In any event, such a regime will always find opposition from those quarters that generate wealth from opaqueness. Efforts to reduce complexity and bring transparency into the “shadow” banking system are laudable first steps. The role of regulation in enabling these social goals is a little more complicated. One of the main arguments supporting self-regulation has been that reputational considerations would cause large institutions to behave themselves. The collapse of Lehman, Bear Stearns, and the recent scandals with Goldman Sachs suggests that such reliance was misguided. It is equally obvious that the efforts of rules-based regulation to rein in the excesses of securitization have failed as well. It could be argued that this failure was unavoidable in an era where the prevailing philosophy has been one of deregulation. In such an environment, political expediency and the power of the banking lobby may have resulted in compromises that render these regulations somewhat toothless. Perhaps in belated recognition of these circumstances, one of the current proposals being debated in Congress is a clearer specification of the level of risk retention by originators in securitizations. For such rules to be effective however, they should not be pronounced in isolation, but rather as part of broad principles with harsher penalties in the event of their 42 Of course this depends on the extent to which the hold-to-maturity approach of the Federal Reserve is successful. 27 violation. At present, with the rather tenuous state of global financial markets, the focus appears to be more on firefighting rather than a concerted effort at addressing this big picture. 6. Conclusions. The paper describes the process of asset securitization and its attempts to manage interest rate and credit risk as it operates within (and tries to circumvent) the prescriptions of accounting, legal and banking regulations. The role of securitization to the banking business is viewed from its location on a lender risk continuum. Securitization was viewed as a middle ground between an extreme banking entity that held all the loans it originated and another extreme entity that distributed all originated loans. The exact amount of risk retention by securitization sponsors has been masked in the bankruptcy remote character of true-sale accounting, off-balance sheet transactions, circumventions around the consolidation of financial statements, and the magic of ratings. The paper then identifies the different aspects of rules-based regulation that attempted to rein in the excesses of complex securitizations. It is clear that securitization activities have greatly benefited by the hubris of the prevailing political philosophy of deregulation. The concern in those quarters is that the “gains” to marketbased solutions will be reversed due to shifting investor sentiment and their reaction to the frequency with which vested interests appear able to profit from the system. Whether “this time is different” or not, the inescapable fact is the significant amount of debt on government balance sheets and that private debt has been socialized. Any cost-benefit analysis of securitization should compare the societal benefits of home-ownership and the ease of access to credit with the cost of this never-ending bailout. Such an analysis will aid in determining the optimal location of securitization in the conceptual risk continuum described in the paper. The paper urges that a focus on the political economy of securitization is what is necessary to continue the ongoing experiment we call capitalism. 28 References Bake, M., K. Hawken, C. Hitselberger, R. Hugi and J. Kravitt, 2010, “Basel II Modified in Response to Financial Crisis,” Journal of Structured Finance, 15(4), 19-28. Black, J., 2008, “Forms and Paradoxes of Principles-Based Regulation,” Working Paper, Law, Economics and Society, London School of Economics. Caprio, G. A. Demirguc-Kunt, and E.J. Kane, 2009, “ The 2007 meltdown in structured securitization: Searching for lessons not scapegoats,” The Paolo Baffi Center for Central Banking and Regulation, Working Paper-2009-49. Calomiris, C.W. and J.R. Mason, 2004, “Credit Card Securitization and Regulatory Arbitrage,” Journal of Financial Services Research, 26(1), 5-27. Covitz, D., N. Liang, and G. Suarez, 2009, The Evolution of a Financial Crisis: Panic in the Asset-Backed Commercial Paper Market, Finance and Economics Discussion Series, Divisions of Research & Statistics and Monetary Affairs, Federal Reserve Board, Washington, D.C. Date, R. and M. Konczal, 2010,” Out of the Shadows: Creating a 21st century Glass-Steagall,” in Make Markets, Be Markets, The Roosevelt Institute Project on Global Finance. Donohue, C., 2009,” Testimony at the joint CFTC-SEC Harmonization Meeting, “ September. Duffie, 2007, “Innovations in Credit Risk Transfer: Implications for Financial Stability,” Working Paper, Stanford University. Fender I. and S. Mitchell, 2009, “The Future of Securitization: How to align the incentives,” Bank of International Settlements, September. Financial Services Authority, U.K., 2007,” Principles-based regulation: Focusing on outcomes that matter,” 1-25. Goetzmann, W.N. and F. Newman, 2009, “Securitization in the 1920’s,” Working Paper, Yale University, http://ssrn.com/abstract=1546102. Gorton, G. and A. Souleles, 2005,”Special Purpose Vehicles and Securitization,” National Bureau of Economic Research. Gorton, G., 2009a, “Slapped in the Face by the Invisible Hand: Banking and the Panic of 2007,” Remarks at the Financial Innovation and Crisis Conference, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta. Gorton, Gary and Andrew Metrick 2009b, “Securitized Banking and the Run on Repo,” http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1440752. 29 Gorton, 2010, Questions and Answers about the Financial Crisis: Prepared for the U.S. Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, 1-17. Hancock, D., A. Lehnert, W. Passmore and S.M. Sherlund, 2005, “An Analysis of the Potential Competitive Impacts of Basel II Capital Standards on US Mortgage Rates and Mortgage Securitizations, Federal Reserve Board. Hansel, D.N and J. Krahnen, 2007, “Does credit securitization reduce bank risk?Evidence from the European CDO market,” Working Paper, Goethe University, Frankfurt, Germany. Kacperczyk M. and P. Schnabl, 2009, “When Safe Proved Risky: Commercial Paper During the Financial Crisis of 2007-2009,” Working Paper, NYU Stern School of Business and NBER. Kane, E.J., 2009, “Financial Economists Roundtable Statement on Reforming the Role of the Rating 'Agencies' in the Securitization Process, Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 21(1), 2833. Kettering, K. , 2008, “Securitization and its discontents: The dynamics of financial product development,” Cardozo Law Review 29(4), 1554-1727. Levitin, A.J., A.D. Pavlov and S. Wachter, 2009, “Securitization: Cause or remedy of the financial crisis?” University of Pennsylvania Law School Research Paper No. 09-31. Loutskina, E, 2005,”Does securitization affect bank lending?Evidence from bank responses to funding shocks,” Carroll School of Management, Boston College. Jiangli, W. and M. Pritzker, 2008,” The impacts of securitization on US bank holding companies,” http://ssrn.com/abstract=1102284. Reinhart, C.M. and K.S. Rogoff, 2009, “The Aftermath of Financial Crises,”American Economic Review 99, 466‐72. Reinhart, C.M. and K.S. Rogoff, 2010, “From Financial Crash to Debt Crisis,“ Working Paper # 15795, National Bureau of Economic Research. Robinson, K.J, 2009, “TALF: Jump-Starting the Securitization Markets,” Economic Letters, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas 4(6), 1-7. Sabry, F. and C. Okongwu, 2009, “Study of the Impact of Securitization on Consumers, Investors, Financial Institutions and the Capital Markets,” NERA Economic Consulting for the American Securitization Forum, 1-241. Swagel, P., 2009, “The Financial Crisis: An Inside View,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. 30 Unregulated Financial Markets and Products, Final Report of the Technical Committee of the International Organization of Securities Commissions, September 2009. U.S. Department of the Treasury, 2009, Financial Regulatory Reform: A New Foundation: Rebuilding Financial Supervision and Regulation. Final Report, 1-88. 31 Figure 1 Securitization rates as a proportion of MBS issuance 32 Figure 2 The structure of securitization Guarantor Asset Manager ManaMana Trades Assets ger Loans Mortgages Originator (sponsor, pools assets) Insures Tranches Senior SPECIAL PURPOSE VEHICLE Assets | Liabilities True-sale assets Funds funds from Bond sales payments from pool Bonds Mezzanine Equity Collects CF from pool Oversight INVESTORS Servicer Trustee Source: Adapted from Fender and Mitchell (2009) 33