Erikson's Stages (cont'd)

advertisement

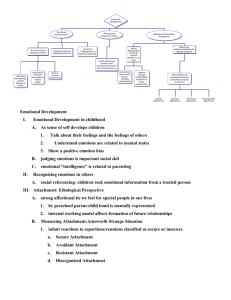

Chapter Five Entering the Social World: Socioemotional Development in Infancy and Early Childhood 5.1 Trust & Attachment: Learning Objectives • What are Erikson’s first three stages of psychosocial development? • How do infants form emotional attachments to mother, father, and other significant people in their lives? • What are the different varieties of attachment relationships, how do they arise, and what are their consequences? • Is attachment jeopardized when parents of infants and young children are employed outside of the home? Erikson’s Stages of Early Psychosocial Development • Each of 8 stages involves a unique challenge – Successful resolution results in a particular strength of psychosocial development – Failure may stunt development, the relevant strength, and impede resolution of future challenges • Three of his stages and strengths are relevant to infancy and the preschool years Erikson’s Stages (cont’d) • Basic trust vs. mistrust (infancy) – Infants depend on caregivers to meet their needs and provide comfort – If needs are not met, the child develops wariness and a lack of comfort – When caregivers responsively and consistently meet these needs, the child develops a basic sense of trust and openness – Hope: the strength involving openness to new experience, tempered by wariness that discomfort or danger may arise; acquired with a proper balance of trust and mistrust Erikson’s Stages (cont’d) • Autonomy vs. doubt (1-3 years) – Children realize they can have control over their own actions and act independently – If autonomy is not achieved, children can feel ashamed of their capabilities and start to doubt them – Will: a strength involving children’s knowledge that they can act on their world intentionally but within limits; arises from a blend of autonomy, shame, and doubt Erikson’s Stages (cont’d) • Initiative vs. guilt (3-5 years) – Guilt can arise when taking initiative places children in conflict with others or when they pursue their own ambitions without cooperating with others – Initiative may develop when children successfully play with different roles (e.g., as a parent) and explore possibilities for themselves – Purpose: a strength involving balance between individual initiative and a willingness to cooperate with others The Growth of Attachment • Attachment to caregivers is a critical aspect of Erikson’s first stage (basic trust vs. mistrust) • Evolutionary psychology: many human behaviors are successful adaptations to the environment – Humans are social beings who also form parent-child attachments – These are adaptations promoting survival to the reproductive years, thereby sustaining the species’ existence The Growth of Attachment (cont’d) • Attachment: an enduring socioemotional relationship with an adult – Ensures survival – Likeliest when the caregiver is responsive and caring – Often formed with mothers, because they usually are primary caregivers – Can occur with any responsive and caring person • Bowlby proposed four stages of attachment Steps Toward Attachment • Preattachment stage (birth to 6-8 weeks) – Infants rapidly learn to recognize their mothers – Infants display many behaviors that elicit adult caregiving (e.g., crying, smiling) • Attachment in the making (6-8 weeks to 6-8 months) – Infants behave differently toward familiar versus unfamiliar adults – Infants are more easily consoled by familiar adults and act happier in their presence Steps Toward Attachment (cont’d) • True attachment (6-8 months to 18 months) – Infants have singled out a “special” adult as their secure and stable socioemotional base • Reciprocal relationships (18 months on) – Toddlers act as true partners in the relationship, taking initiatives in interaction – Can anticipate that parents will return after a separation, which benefits coping – Toddlers begin to understands parents’ feelings and goals • May use these to guide their own behavior (e.g., social referencing) Father-Infant Relationships • Attachment to fathers tends to follow that with mothers • Fathers tend to spend more time playing with children than taking care of them • Fathers play with children differently than mothers (more rough and tumble) – Mothers more often read to children and talk with them • Children tend to seek out the father for a playmate; mothers are preferred for comfort Forms of Attachment • Ainsworth’s Strange Situation paradigm – Three phases (~3 minutes each) • Child and mother first occupy an unfamiliar room filled with toys • Mother leaves room momentarily • Mother then returns to room – Observe child’s reactions during each – Classified four types of attachment • Three were insecure types (least frequent) • One is secure (frequent) Four Types of Attachment Relationships • Secure attachment (60-65%): baby may or may not cry upon separation; wants to be with mom upon her return and stops crying • Avoidant attachment (20%): baby not upset by separation; ignores or looks away when mom returns • Resistant attachment (10-15%): separation upsets baby; remains upset after mom’s return and is difficult to console • Disorganized attachment (5-10%): separation and return confuse the baby; reacts in contradictory ways (e.g., seeking proximity to the returned mom, but not looking at her) Strange Situation Paradigm Criticisms • Cultures may vary in what they consider appropriate responses to separation and reunion; ergo, we cannot rely on these alone • Attachment Q-set: observers watch moms and children interact at home, then rate numerous attachment-related behaviors to form a total score – Scores from Strange Situation and Q-set correlate highly and both predict later quality of relationship (e.g., insecurely attached infants later report anger with parents and low intimacy with them) Consequences of Attachment • Environmental instability and stress may cause changes in the quality of attachment (from secure to insecure) – Early attachment may not well predict later outcomes partly due to these factors • Early secure attachment predicts – successful and confident peer relationships – fewer conflicts with friends – more stable and higher-quality romantic relationships Consequences of Attachment (cont’d) • Early disorganized attachments predicts problems with anxiety, anger, and aggression • Two mutually nonexclusive explanations of why early attachment is a strong predictor 1. Early relationships teach children to trust and confide in others, leading to skilled social relationships 2. Parents who establish early secure attachments remain warm and supportive throughout childhood What Determines Quality of Attachment? • Secure attachment results from predictable, sensitive, and responsive parenting: Why? – Internal working model: a child’s set of expectations about parents’ availability and responsiveness, in general and during stress • Positive model: this person is dependable, caring, plus concerned about my needs and willing to meet them • Negative model: this person is uncaring, undependable, unresponsive, and even annoyed by my needs What Determines Quality of Attachment? (cont’d) • Temperament also contributes to attachment – Fussy and difficult-to-console babies are somewhat less likely to form secure attachments • Particularly for rigid and traditional mothers than accepting and flexible ones • Parental training helps parents interact more affectionately, responsively, and sensitively – Promotes secure attachments and positive internal working models Attachment, Work, & Alternate Caregiving • Quality of mother-child attachment for 15- and 36month-olds is unrelated to – – – – daycare’s quality or length of stays number of changes in daycare age when this care began type of childcare (e.g., childcare center vs. in the home with a nonrelative) – child forming attachments to nonparental caregivers • Insecure attachments are likelier given low-quality or frequent childcare combined with moms who already are unresponsive and insensitive Features of High-Quality Daycare • Low ratio of children to caregivers • Well-trained, experienced staff • Low staff turnover • Ample opportunities for educational and social stimulation • Good communication between parents and daycare workers about the program’s goals and routines • Sensitive and responsive caregiving is key 5.2 Emerging Emotions: Learning Objectives • At what ages do children begin to express basic emotions? • What are complex emotions, and when do they develop? • When do children begin to understand other people’s emotions? How do they use this information to guide their own behavior? Experiencing and Expressing Emotions • Emotions have functional (adaptive) value (e.g., guiding behavior and facilitating relationships) • Theorists distinguish complex from basic emotions – Basic emotions consist of • a subjective feeling • a physiological change • an overt behavior – They consist of joy, sadness, anger, fear, distress, disgust, interest, and surprise – All have emerged by 8 to 9 months • Studying infants’ facial expressions and overt behaviors reveals their probable trajectory Development of Basic Emotions • Newborns: pleasure and distress • 2 to 3 months: sadness • 2 to 3 months: social smiles – occur upon seeing a human face – sometimes accompanied by cooing – express pleasure at seeing another 4 to 6 months: anger - reflects an increasing understanding of goals and their frustration Development of Basic Emotions (cont’d) • 6 months: stranger wariness - child looks away and begins to fuss - occurs once children start to locomote - adaptive as a natural restraint against wandering away from familiar others - occurs less with strangers in a familiar environment - wanes once children can recognize friendly faces • 6 months: disgust adaptive in signaling toxins (e.g., feces) or potential illness (e.g., vomit) Emergence of Complex Emotions • Complex emotions include guilt, embarrassment, and pride • To be experienced, child first must understand the self and behavior in relation to whether they have met standards or expectations • This self-understanding emerges around 1518 months • Complex emotions emerge at 18-24 months Later Developments • With increasing cognitive development, children experience basic and complex emotions in more and different situations – Ex.: fear of the dark or imaginary creatures declines during elementary school • understand appearance vs. reality – Ex.: elementary school but not preschool children would experience • shame for not defending a peer • normative fear about school, health, and personal harm Cultural Differences in Emotional Expression • Many basic and complex emotions are expressed similarly around the world • Expressing emotions differs across cultures – Asian children are encouraged to show emotional restraint – European-American 11-month-olds cried and smiled more than Chinese infants of same age Cultural Differences (cont’d) • Cultures differ in which events trigger emotions • Asian children are proud of class-wide achievement • American children are proud of public personal achievement, whereas Asians are embarrassed • American children express anger at others for ruining their property or hurting them • Asian-Buddhist children would inhibit anger and feel shame instead for their possible role in the event Recognizing & Using Others’ Emotions • Adults are more skilled at recognizing subtleties in emotion and detecting when others are faking an emotion • 4-6 months: differentiate among faces expressing happiness, sadness, and fear • Like adults, infants attend more to facial expressions of negative emotions than happy or neutral ones (adaptive value) • Infants understand a facially displayed emotion as shown by them matching their emotions to other people’s Recognizing Others’ Emotions (cont’d) • Social referencing: 12-month-old infants use adults’ (e.g., parents’) facial and vocal emotion displays to direct their own behavior – A child will • avoid an object if parent expresses fear or disgust • approach the object if parent shows happiness • 14-month-olds remember earlier observed emotional reactions of parents to particular objects • 18-month-olds use the reactions of one adult to another adult’s behavior to guide their own behavior Recognizing Others’ Emotions (cont’d) • Factors contributing to children’s emotion understanding – parents and children frequently discussing past emotions (especially negative ones, such as fear and anger) – parents explaining how feelings differ and feelings’ situational elicitors – a positive and rewarding relationship with parents and siblings – possibly contributes due to more frequent discussions about a full range of emotions Regulating Emotions • Emotion regulation: controlling in some way what one feels and how to communicate the feeling • Dependent on cognitive processes - Attention (e.g., reducing anger by diverting attention to less provocative stimuli, thoughts, or feelings) - Reappraisal (e.g., lessening an emotion’s intensity by differently interpreting the significance or meaning of an event or feeling) • Across age, some children more poorly regulate their emotions compared to others, which can create adjustment problems (e.g., peer conflicts) Regulating Emotions (cont’d) • 4-6 months: use simple strategies to regulate emotions (e.g., turning away from a scary image) • 24 months: because it better gets an adult’s attention and help, express sadness rather than fear or anger • Older children and adolescents – become better able to control their own emotions rather than relying on others – use mental strategies to regulate emotions – tailor their strategy to the particular situation (e.g., whether its avoidable or not) 5.3 Interacting with Others: Learning Objectives • When do youngsters first begin to play with each other? How does play change during infancy and the preschool years? • What determines whether children help one another? The Joys of Play • Even two 6-month-olds look, smile, and point at each other • 12 months: parallel play, in which children play alone but are keenly interested in what others are doing • 15-18 months: simple social play, in which children do similar activities and talk or smile at each other • 24 months: cooperative play, theme-based play where children take special roles (e.g., hide-andseek) Make-Believe • Values and traditions are expressed through make-believe or imaginary characters • Entertaining, while promoting cognitive development • Helps children explore frightening topics • Imaginary playmates promote imagination, sociability, and adjustment • Pretend play is a regular part of preschooler’s play 16-18 months understand difference between pretending vs. reality Solitary Play • Usually not an indicator of problems • Can reflect uneasiness with others for which professional help should be sought if child – wanders aimlessly among others – hovers over others who are playing Gender Differences in Play • 24-36 months: children spontaneously prefer playing with same-sex peers – Not restricted to gender-typed games – Resist adult encouragement to play with the opposite sex – Increases through to pre-adolescence • Why? Gender-typed play styles, such as • boys prefer rough and tumble, competition, and dominance • girls are more cooperative, prosocial, and conversation-oriented Gender Differences in Play (cont’d) Why the same-sex play preference? (cont’d) • Girls are more enabling – Their acts and remarks support others and sustain interactions • Boys are more constricting – try to be the victor by exaggerating, and threatening or contradicting the other • Evolutionarily adaptive? – Males strive to establish a high rank to gain access to more mates – Females have affiliation goals, because they traditionally left their community to join another Parental Influence Parental involvement in child’s play can lead to later improved peer relations when parents serve as • playmate, scaffolding the child’s play and rendering it more sophisticated • social director, arranging play dates and official play activities (e.g., swimming) • coach, helping children learn how to initiate interactions, make joint decisions, and resolve conflicts (when done appropriately) Parental Influence (cont’d) • Parents also serve as mediators to help children resolve disputes, share, and identify mutually acceptable activities • Parent-child attachment relationships indirectly influence children’s play • When of high quality & emotionally satisfying – children generalize this positive internal working model to peer relationships – children are more confident about exploring their environment, yielding more opportunities to form new relationships Helping Others • Prosocial behavior: one that benefits another – Ex.: cooperating, being polite • Altruism: prosocial behaviors not directly benefiting the self, but driven by feelings of responsibility toward others – Ex.: sharing one’s lunch with a friend who forgot his; helping a lost child • Adaptive? Increases person’s chances of receiving help, thereby promoting survival, later sexual reproduction, and passing along these genes Helping Others (cont’d) • 18 months: recognize others’ distress signals and will try to comfort them; will help someone in need (e.g., helping a teacher pick up markers she/he dropped) • By 3 years: are gradually starting to understand others’ needs and learning appropriate altruistic responses – Still somewhat limited because of egocentrism in distinguishing others’ needs or desires from their own Skills Underlying Altruistic Behavior • Perspective-taking: accurate perception of another’s physical, social, or emotional viewpoint as distinct from one’s own – Empathy is one manifestation: the actual experience of another’s feelings – The state and trait of empathy promote helping Situational Influences Why do even kind children sometimes act cruelly? Help is likelier when children – feel responsible for the person in need, which reminders of friendship’s or affiliation’s importance can promote – believe they have the skills to be helpful – are in a good rather than a bad mood – incur fewer costs or sacrifices for helping The Contributions of Heredity • Prosocial behavior is more similar in identical twins than fraternal ones • Genes influence aspects of temperament related to prosocial behavior • Certain children are aware of another’s need, but – feel so distressed that they cannot figure out how to help due to poor emotion regulation skills – their inhibition (shyness) prevents them from helping, despite knowing how Socialization of Altruism Children are more prosocial and/or empathic when parents • model warmth and concern for others • model being cooperative, helpful, and responsive • discipline warmly and supportively, set guidelines, and give feedback • use reason while disciplining, stating how children’s actions affect others • provide children opportunities to behave prosocially in and outside the home 5.4 Gender Roles & Gender Identity: Learning Objectives • What are our stereotypes about males and females? How well do they correspond to actual differences between boys and girls? • How do young children learn gender roles? • How are gender roles changing? What further changes might the future hold? Images of Men & Women: Facts & Fantasy • Social role: cultural guidelines as to how we should behave, especially with others – Gender roles are one of the first learned • Learning gender stereotypes – Our world is not gender neutral – 18 months: girls and boys look longer at gender-stereotyped pictures of toys – 4-year-olds: extensive knowledge of genderstereotyped activities and some behaviors or traits Images of Men & Women: Facts & Fantasy (cont’d) • Preschool: believe boys are physically, but girls verbally, aggressive • Post-preschool: continuously growing beliefs about gender-stereotyped traits and occupations – Males will have more prestigious jobs (earn more money, have greater power) – Boys are strong and dominant, whereas girls are emotional and gentle – Recognize gender stereotypes as behavioral guidelines that are not necessarily binding Gender-Related Differences How do boys and girls actually differ? • Verbal ability: girl toddlers have larger vocabularies; thereafter read, write, and spell better, and have fewer language problems • Mathematics: in cultures not limiting females to traditional stereotypes, this gender gap has diminished in the past 25 years • Spatial ability: from infancy onwards, boys more accurately and rapidly solve visualspatial problems Gender-Related Differences (cont’d) • Social influence: girls comply more with adult directions and more readily accept others’ influence attempts, possibly because they value group harmony • Aggression: starting at 17 mos., boys are more physically aggressive (across cultures) • Girls are likelier to engage in relational aggression – Hurt others by damaging their peer relationships (e.g., gossip, ignore, spread rumors) Gender-Related Differences (cont’d) • Emotional sensitivity: girls are more empathic; can better express and interpret others’ emotions • Caveats about gender differences - They depend on experience - Historical changes affect them - Most differences are small, reflecting only the average difference between groups of boys and girls • Ex.: some girls may outperform boys on spatial tasks, while some boys may be more emotionally sensitive than girls Gender Typing • Parents are equally warm and encouraging to boys and girls • However, results show parents to model and differentially reinforce “appropriate” gendertyped behaviors, with – girls playing with dolls, dressing up – boys engaging in rough-and-tumble play, playing with blocks, mild aggression • Results support social learning theory Gender Typing (cont’d) • Differential reinforcement of gender-typed traits and behaviors is likelier in – parents with traditional views of each gender’s rights and roles – fathers, who punish their sons more for gender-atypical behavior, and are more accepting of dependence in girls • Mothers rarely contradict or question children’s gender-stereotyped statements Gender Typing (cont’d) • Peers influence gender roles in two ways – Children learn more about their role from like-sex than opposite-sex peers by engaging so often in same-sex play • sharpens one’s sense of gender group membership • heightens the contrast between each gender’s roles and behaviors – Peers treat boys even more harshly than girls for “feminine” activities and interests Gender Identity Gender identity: sense of self as male or female • When is this formed? Kohlberg’s three stages – Gender labeling: understanding that one is a girl or boy and labeling the self as such (2-3 years) – Gender stability: understanding that one will forever be a boy or girl (preschool) – Gender constancy: understanding that one’s maleness or femaleness does not transform across situations, or with personal wishes and superficial changes (4 to 7 years) Gender Identity (cont’d) • Kohlberg: only after obtaining gender constancy (Stage 3) do children start learning gender roles – Some results show this learning to occur earlier, after mastering gender stability (Stage 2) – Gender constancy does help children think more flexibly about gender roles (e.g., ok for girls to play with trucks or boys with dolls) – This theory addresses when but not how children learn about gender or genderappropriate behaviors Gender Identity (cont’d) • Gender-schema theory: addresses “how” children learn about gender and gender roles – Children decide if objects, activities, or behaviors are “male” or “female” and then decide whether they should learn more about these • Once children understand or refer to themselves by gender, they play more often with genderstereotyped toys (17-21 mos.) and watch gendertyped TV shows and evaluate toys more positively if a child of their sex likes the toy Biological Influences • Evolutionary theory: men and women evolved different traits and behaviors adaptive to their unique investments (e.g., childrearing for women and resource provision for men) • Identical twins are even more similar than fraternal twins in preference for sex-typical toys and activities • In utero testosterone exposure predicts preference for masculine-typed activities Biological Influences Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH): genetic disorder of the adrenals secreting large amounts of androgen; affects girls, such that – their enlarged clitoris can resemble a penis – they prefer masculine activities and male friends – hormone therapy and sex operations do not undo these preferences – greater prenatal androgen exposure exacerbates these preferences – it seems to affect brain regions critical for gender-role behavior VIDEO: Child with Gender Identity Disorder Evolving Gender Roles • Family lifestyles, culture, and history influence children’s gender roles • Family Lifestyles Project: studied 1960-70s counterculture members who socialized their children without traditional gender beliefs – Children did not stereotype occupations or object use (e.g., girls can use a hammer or boys an iron) – Children did prefer same-sex friends or activities • Evolutionary history partly continues to influence certain roles (e.g., women being nurturing or men being protectors and providers)