Week1

advertisement

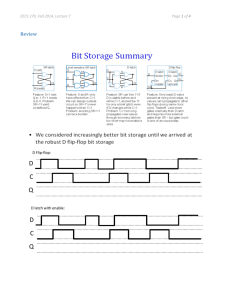

EECS 170C Lecture Week 1 Spring 2014 EECS 170C Prof. M. Green / U.C. Irvine 1 Lowpass Filter Example C2 =1 pF Vin ideal op-amp Vout From standard circuit analysis: R2 Av = =1 R1 f 3dB Spring 2014 EECS 170C 1 = = 159 MHz 2p × C2 R2 Prof. M. Green / U.C. Irvine 2 Lowpass Filter Design R2 Specifications: Av = 2 f3dB = 500 MHz Vin R2 Av = =2 R1 1 f 3dB = = 500 ´10 6 2p ×C 2 R2 Spring 2014 EECS 170C R1 C2 ideal op-amp Vout 2 equations with 3 unknowns not a unique solution! Prof. M. Green / U.C. Irvine 3 Additional constraint #1: R2 Capacitors should be no larger than 1 pF: Vin Set C2 = 1 pF R1 C2 Vout R2 = 318 R1 = 159 Additional constraint #2: For f > f3dB, magnitude should exhibit -40 dB/decade rolloff: H ( jw ) -20 dB/decade The given circuit topology cannot satisfy this constraint. f3dB Spring 2014 EECS 170C f Prof. M. Green / U.C. Irvine 4 2nd-order filter topology (2 capacitors) needed: R2 Vin R1 C2 R3 Vout C1 H ( s) = - R2 1 × R1 + R3 [1+ sC1 ( R1 || R3 )](1+ sC 2 R2 ) Additional constraint #3: Under the condition that R’s and C’s vary randomly within ±10%, f3B should vary no more than ±5% This constraint is impossible to meet for any RC filter! Spring 2014 EECS 170C Prof. M. Green / U.C. Irvine 5 Possible solution #1: Replace resistors with triode-biased MOSFETs with gates controlled by dc voltage VG, realizing electrically controllable resistors. VG Vin Critical frequencies can be controlled by VG. Vout Possible solution #2: Replace resistors with configuration consisting of capacitor and switches, with switches controlled by clock signal with period Tc. Critical frequencies are determined by Tc and capacitor ratios. Vin Vout Critical frequencies can be controlled by Tc. Spring 2014 EECS 170C Prof. M. Green / U.C. Irvine 6 Aspects of Design (Synthesis) • Desired behavior & specifications are given; component values & circuit topology are not. • Solution is usually found iteratively: An initial circuit is proposed and analyzed. If specifications are not met, the circuit is modified and re-analyzed. • There is usually not a unique solution that satisfies the specifications. However, each solution exhibits its own set of tradeoffs (e.g., size, cost, robustness) that must be considered. • It may not be possible to meet all of the specifications simultaneously using a given technique or technology. Spring 2014 EECS 170C Prof. M. Green / U.C. Irvine 7 Analog vs. Digital Signal Representation Precision in specifying and measuring voltage signal is determined by random noise generated by circuit components. Analog representation: Digital representation: Dynamic Range is determined by ratio of maximum amplitude (usually determined by supply voltage) and noise level. 16 possible digits Spring 2014 EECS 170C Dynamic Range in specifying and measuring digital signal is determined by number of bits used in representing the signal. a3 a2 a1 a0 Dynamic Range = 16 Prof. M. Green / U.C. Irvine 8 Continuous vs. Discrete Methods of Timing Voltage signal is defined at any arbitrary instant of time. There is no limit on the highest frequency that can be generated or measured. Continuoustime signaling: Voltage signal is defined only at discrete values of time kT, where k is an integer. The highest frequency that can be observed is 1/2T – the Nyquist frequency. Discrete-time signaling: Spring 2014 EECS 170C Prof. M. Green / U.C. Irvine 9 Passive Components Power dissipation in a resistor: PD = I ×V = I 2 R ³ 0 Components that always dissipate power are said to be passive. VS2 Power supplied by VS: PS = RS + R L 2 æ RL ö 1 Power dissipated in RL: PL = çVS × ÷ × R S + RL ø RL è PL RL = <1 Power gain: PS RS + RL Power amplification is impossible if only passive components are present. Spring 2014 EECS 170C Prof. M. Green / U.C. Irvine 10 Active Components A component that is not passive is said to be active. PL rin2 RL 2 =A × × PS RS + rin R + r L out ( » A2 × ) 2 rin RL (assuming rin >> RS , rout << RL) Power amplification is possible with active devices -- that’s why we need transistors. Spring 2014 EECS 170C Prof. M. Green / U.C. Irvine 11 Discrete Circuit Realized on a Printed Circuit Board (PCB) Spring 2014 EECS 170C Prof. M. Green / U.C. Irvine 12 Integrated Circuit on a Monolithic Substrate Spring 2014 EECS 170C Prof. M. Green / U.C. Irvine 13 Circuit Realization: Discrete vs. Monolithic • Each component takes roughly the same area on the board independent of its value. • The area of a component is directly related to its value. • Passive components can be chosen to a desired accuracy, subject to cost. • Individual component values exhibit large variances; however, like components with identical geometries in close proximity exhibit very close matching (<1%). • Most circuit nodes can be observed for testing and verification. • Access to the circuit is only through pre-determined nodes that are connected to pads which then bonded out to the package. • Dimensions on order of cm. • Dimensions on order of mm, encapsulated in a package. Spring 2014 EECS 170C Prof. M. Green / U.C. Irvine 14 Example of Matching Design an amplifier with an accurate gain of +10: Assume Av can take values between 10,000 and 50,000. V+ = Vin R2 R1 + R2 = Av (V+ - V- ) V- = Vout × Vout Vout 1 = 1 1 Vin + Av 1 + R1 R2 Very small depends only on resistor ratio Let R1 = 9k , R2 = 1k: Av = 10,000 Vout /Vin = 9.990 Av = 50,000 Vout /Vin = 9.998 Spring 2014 EECS 170C independent of individual resistor values Prof. M. Green / U.C. Irvine 15 Manufacturability of ICs 1. Die Size X X X Spring 2014 EECS 170C Prof. M. Green / U.C. Irvine 16 2. Power Dissipation Power dissipated in the IC is converted to heat, raising the temperature of the die & package. Elevated die temperature can degrade circuit performance or even permanently damage the silicon. To accelerate heat removal, a heat sink may need to be used, requiring more space. Passive heat sinks Spring 2014 EECS 170C Active air-cooling heat sink Prof. M. Green / U.C. Irvine 17 3. Robust Design IC must operate properly in the presence of variations in: • Processing in fabrication technology • Individual component values can vary ±15% or more • Voltage supply • Supply voltages can vary ±10% • Temperature • Circuit should operate to spec at 0--70° C ambient temperature Spring 2014 EECS 170C Prof. M. Green / U.C. Irvine “PVT” 18 Use of Approximation KCL at Vout: ( aF IES eVX KCL at VX: VT ( (2 - aF ) eVX Spring 2014 EECS 170C Prof. Prof. M. Green M. Green / U.C. Univ. of California, Irvine Irvine ) æ (V -V ) -1 - IES çe in out è VT ) -1 + ( VT ö -1÷ = 0 ø ) 1 VX -VCC = 0 R 19 My Research 1. High-speed frequency divider: The operation of “real” high-speed clock dividers is more complex … Spring 2014 EECS 170C Prof. M. Green / U.C. Irvine 20 Clock divider based on CML D flip-flop: æW ö ç ÷ è L øD æW ö ç ÷ è L øD æW ö ç ÷ è L øC æW ö ç ÷ è L øL æW ö ç ÷ è L øL æW ö ç ÷ è L øC æW ö ç ÷ è L øD æW ö ç ÷ è L øD æW ö ç ÷ è L øL æW ö ç ÷ è L øC æW ö ç ÷ è L øL æW ö ç ÷ è L øC Divider sensitivity curve: Vmin = minimum input clock amplitude required for correct operation. (function of input frequency) fso = self-oscillation frequency Vmax Spring 2014 EECS 170C Vmax = maximum dc differential voltage that can be applied to the input clock for which the circuit self-oscillates. Prof. M. Green / U.C. Irvine 21 Divider test chip measurements Divider chip photograph Designed at Broadcom using 0.13 µm CMOS process; shunt-peaking was used. Spring 2014 EECS 170C Measured sensitivity curves: a) Conventional (DFF) divider b) Modified regenerative divider c) Ring oscillator divider Prof. M. Green / U.C. Irvine 22 2. Equalization of broadband receivers: • Normally the equalizer and CDR are designed and implemented as separate blocks. • Common elements in each of the two blocks can be identified and combined... Spring 2014 EECS 170C Prof. M. Green / U.C. Irvine 23 Circuit Details • Shunt-peaking CML summer. • 2-stage shunt-peaking CML slicer. • Differentially-tuned LC VCO. • Retimer generates low-ISI retimed data. Spring 2014 EECS 170C Prof. M. Green / U.C. Irvine 24 Measurement Setup Cable Anritsu MP1763B Pattern Generator 1.8V Anritsu 69137B Synthesized Signal Generator INDATA_P DFE & CDR INDATA_N RF Clock OUT_CLK_N OUTDATA_P Trigger Clock OUTDATA_N OUT_CLK_P V_UP V_DOWN Die photo. Implemented in Jazz Semiconductor 0.18µm BiCMOS Process (only CMOS transistors used). HP 83480A Oscilloscope Test setup Test board Spring 2014 EECS 170C Prof. M. Green / U.C. Irvine 25 Equalizer + CDR Operation (2) 2.4 m cable Cable output eye diagram. Recovered clock RJ = 1.83 ps rms Retimer output eye diagram Jitter = 4.14 ps rms Cable output eye diagram. Recovered clock RJ = 2.15 ps rms Retimer output eye diagram Jitter = 4.96 ps rms 3.6 m cable Spring 2014 EECS 170C Prof. M. Green / U.C. Irvine 26 2. Equalization of broadband receivers: 4:1 Multiplexer Tree Structure: Din0 Q D D-FF Din1 D Q D Q A B Select Latch D-FF Q D A B Select D-FF retimer 10 GHz D Din2 Q D 20 GHz 40 GHz A B Select Q D Q D Latch D-FF D-FF Din3 Q D Latch D-FF Q 20 GHz 10 GHz 10 GHz 10 GHz Spring 2014 EECS 170C Prof. M. Green / U.C. Irvine ÷ 2 20 GHz ÷ 2 40 GHz PLL 27 Dout 40GHz Differential Push-Push VCO Resonates at 40 GHz Virtual ground node Resonates at 20 GHz Spring 2014 EECS 170C Prof. M. Green / U.C. Irvine 28 Chip Board and Die Micrograph 20 GHz clock 40 Gb/s output 40 Gb/s output 40Gb/s Distributed buffer 625 MHz Reference clock 20 GHz clock output Push-push differential VCO 40Gb/s MUX and retimer Clock buffers PLL 20Gb/s inputs 20 Gb/s inputs Spring 2014 EECS 170C Prof. M. Green / U.C. Irvine 29 Measured 40 Gb/s Output 40Gb/s MUX output (Differential) with 450 mV differential peak-to-peak vertical eye opening and 1.14 ps rms jitter Spring 2014 EECS 170C Prof. M. Green / U.C. Irvine 30