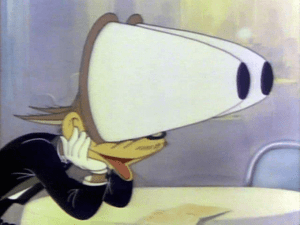

Tex Avery and the Liberal Animation Revolution

advertisement