A Curious Case of Political Legitimacy

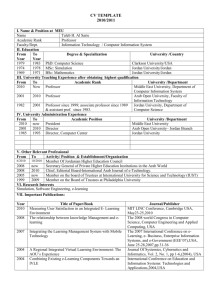

advertisement