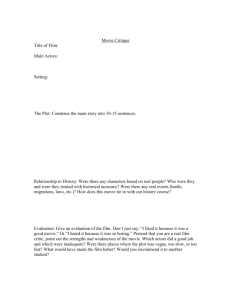

Movie Review Guidelines

advertisement

Page |1 Movie Review Guidelines When writing a movie review you should follow certain expected conventions associated with the discussion of film. Step 1 If you have not been asked to review a specific movie choose a movie that is appropriate for the assignment. A movie review assignment may allow you leeway to review a movie that is not considered appropriate for publication. Inquire with your teacher as to your choice of movie, but keep in mind that the bulk of the student body will be too young to attend a movie rated above PG-13 without parental supervision and so you may be reviewing a movie that most students have not seen or will not see as a result of your review. Step 2 Introduce the movie by title and mention any stars or the name of the director if famous. Insert into the opening paragraph a thesis or overriding topic of your review. Instead of telling your readers that the movie is really great or simply awful, highlight one of the best or worst aspects of the film. Choose a highlight like innovative special effects, an actor's performance that dominates the movie, a lack of logic in the plotline or some other aspect that sticks out. Step 3 Avoid relating the entire plot of the movie in your review. Do not turn the review into a synopsis of the film. Insert a SPOILER ALERT above a paragraph that reveals a surprise plot turn if you cannot adequately relate the essence of the movie's plot without the revelation. Try to find ways to avoid any spoilers while still getting the point of your review across. Document1 Page |2 Step 4 Address the film in the context of its genre. Become aware of what audiences generally tend to expect from a science fiction epic, a romantic comedy or a tearjerker drama. Inform yourself about the conventions and clichés associated with specific movie genres so that you can recognize and relate to your readers such examples as how the science fiction movie breaks new ground in special effects or how the romantic comedy is little more than a collection of the most obvious clichés associated with that genre. Step 5 Analyze all the components that make up a good or bad movie and provide insight into how these components are addressed in the movie you are reviewing. For example, state that the acting is very good, but the storyline presents nothing new or interesting; use examples to show how the direction of the movie is creative, but not enough to fill in gaping plot holes. Step 6 Conclude with your recommendation to see the movie or not, giving specific reasons as to whether it is worth the price of admission. Elements of film review: David Bordwell suggests in his book Making Meaning, that there are four key components present in film reviews. These components consist of a condensed plot synopsis, background information, a set of abbreviated arguments about the film, and an evaluation. Condensed Plot Synopsis A condensed plot synopsis means exactly that. This is a brief description of the film's plot that probably emphasizes the most important moments of the film without revealing the films ending. Nothing is worse than revealing too much about the movie and thus ruining it for the viewer. Document1 Page |3 Background Information Background information about the film consists of information about the stars, the director, and the production staff of the film. It can also include interesting tidbits about the making of the film. It may incorporate information about the film's source material as well as mentioning the type of genre the film fits into. If the reviewer is so inclined, it may also include comments from other reviewers and industry insiders that are designed to indicate to the reader what the film's reception is likely to be (can you say hype?). Abbreviated Arguments About The Film The abbreviated arguments about the film are generally the main focus of the review. This is the section in which the reviewer analyzes and critiques the film. The focus of this segment is to point out what does and does not work in the movie and why. Most reviewers attempt to combine this information with a little background information. For example, if the lighting and composition of the film are particularly dreadful the reviewer will generally take the time to note who the film's cinematographer was - since it's the cinematographer's responsibility to prevent that from happening. Evaluation The reviewer's evaluation of the film generally includes a recommendation to either see or avoid seeing the film. This evaluation is always based on the reviewer's arguments about the film and is frequently backed up with his/her comments regarding the film's background. Your instructor would argue that the entire tone of the review should be influenced by the reviewer's evaluation of the film. To be honest, the reader should have a fairly clear idea of the reviewer's opinion after they have read the review's opening sentence. This does NOT mean that you should start a review with statements like, "This was a good movie," or "you should go see this film right now!" It does mean that the reader should have a general idea about where the reviewer stands on the film from the first paragraph on - just don't bludgeon us to death with it. Generally speaking, when a reviewer is evaluating a film he/she tends to be assessing some, or all, of the following: the motivation for what happens in the film, the film's entertainment value, the film's social relevance and social value, and the film's aesthetic value. Hey, if it were easy everyone would be a film critic. It is a great job, most of the time. Unless of course, you are watching a genuinely bad film, the sort that once caused a notable film critic to comment, "That is 90 minutes of my life I can never get back." Film critics frequently find fault with the film's motivation. That is not to say that they did not like the film's central theme but rather to say that they are looking for the relevance of a particular narrative event, or a justification for a specific action or section of dialogue. Bordwell classifies motivation into four categories: compositional, realistic, intertextual, and artistic. Compositional motivation probes the film's cause-effect logic - that is, does the movie flow logically from one scene to the next. Realistic motivation examines whether the actions that occur within the film are believable within the realms of the film's fiction. Intertextual motivation examines the relationship between the film and its genre and source material (a novel, a play, etc.) - for example, what would make sense in a musical would not make sense in a western and vice versa. Artistic motivation examines the way a film is made, its use of mise-en-shot and mise-en-scene to achieve a particular artistic look and feel. It is important to note that what is artistically motivated to one reviewer may be distracting to another. Once again, it all comes down to individual taste. Document1 Page |4 Most reviewers are at the very least conscious of the film's entertainment value. They are aware that the principle objective of most films is to entertain. They are also aware that if the film does not create a sense of willing suspense of disbelief on the part of a viewer it simply is not entertaining. Another way of looking at it is to say that the audience should be actively engaged in the movie, it should hold their attention and arouse their emotions. At today's ticket prices it had darn well better do that. So how does a movie do that? If I had all the answers I would be in Hollywood consulting for a major studio and this web site could take care of itself! That is not totally true, I do have some theories about this, as do most film critics. For starters, it is my fundamental belief that a film that does not have a strong set of characters with which the audience can identify it will not engage the audience. It should be noted, however, that some films (most notably summer blockbusters), can be successful if they provide the audience with an emotional roller-coaster ride that is comprised of enough action sequences, stunts, loud explosions, special effects, and booming surround sound. This reviewer is particularly fond of fireballs and explosions. Any of these approaches can potentially prove entertaining for the viewer. Social value or relevance can also play an important role in a critic's perspective of the film. If the film makes an important social statement a reviewer may choose to overlook some, if not all of the flaws in the film. Films such as "Citizen Kane" (Orson Welles' masterpiece about the life of Charles Foster Kane which was actually a scathing indictment of the American Dream features many inconsistencies), or "JFK" (Oliver Stone's examination of the assassination of John F. Kenedy which includes many questionable facts) can be forgiven the occasional lapse because of their social and artistic importance. That is to say, a film can sometimes be redeemed by its message to such an extent that a reviewer will overlook technical mistakes, unless they are so monumental that they totally distract the viewer. So, what order does this go in, and how much of each of these things should be included in any review? Actually, that depends on the film and on the reviewer. Generally speaking, the information appears in the aforementioned order, but there is no hard and fast rule that says that it has to be that way. Bordwell seems to suggest that you open with a mini evaluation (one or two sentences that set the tone for the review), provide a mini plot synopsis, insert some condensed arguments (focusing on the acting - or lack therein, story logic, production values, special effects, etc.), toss in some background information throughout these sections, and then finish with a final assessment of the film's relative merit. Just how much the reviewer includes in each of these sections depends both on the film and the reviewer's assessment of his/her readers. Translated: what is there about the film that is worth praising or deriding and just how much information do my readers need and want in order to determine whether they would enjoy seeing this film? Document1