Conservatives With No Choice But to Enlighten

advertisement

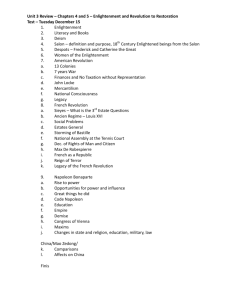

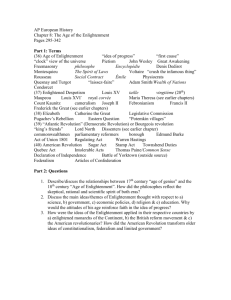

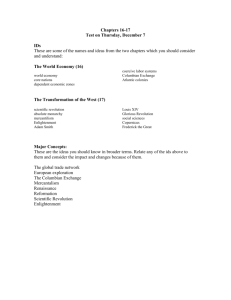

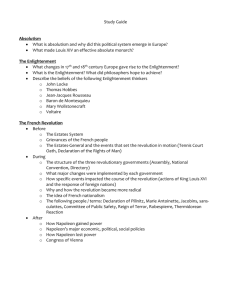

Blake Huneycutt Conservatives With No Choice But to Enlighten In chapter-one of his book Classical Sociological Theory, George Ritzer states, “French sociology has from the beginning been an uncomfortable mix of Enlightenment and counter-Enlightenment ideas.” A statement that is impossible to deny of French sociologist that were born, and therefore theorized in a post-revolutionized France. Both Alexis de Tocqueville and Auguste Comte are seen as historically important sociologists of the Enlightenment Era but are also considered to hold conservative views that were similar to the counter-Enlightenment ideas of that period. George Ritzer describes the Enlightenment as intellectual developments that sought to change philosophical thought and overthrow/replace long-standing ideas by using philosophy and science to comprehend and control the universe by means of reason and empirical research in order create a more rational world. In the chapter-one subsection of “The Conservative Reaction to the Enlightenment”, he considers the counter-Enlightenment as an anti-revolutionary, change-fearing sector of the society that saw rationalism and reason as being inferior to the traditional belief that God created society, therefore is the source of society and that tampering with/disrupting society would cause people to suffer, resulting in social disorder. They found change (industrial, urbanization, bureaucracy) to be a severe threat and emphasized the importance of ritual, ceremony and worship as well as a strong support for social order under the hierarchy. Ritzer uses Louis de Bonald and Joseph de Maistre as direct examples of conservative, counter-revolutionary philosophers, yet both were already in their midforties by the end of the first French Revolution. In contrast, Tocqueville was born in 1805 and Comte was born in 1798, the last year of the first French Revolution. Neither had the opportunity to experience France prior to a revolution, yet instead, according to Comte, lived “at a period of confusion, without any general view of the past, or sound appreciation of the future (119).” Similarly, Tocqueville states, “I came into the world at the end of a long revolution, which, after destroying ancient institutions, created none that could last. When I entered life, aristocracy was dead and democracy was yet unborn. My instinct, therefore, could not lead me blindly either to the one or the other (85).” This confusion, and unstable societal structure, brought both of these theorists into a world that forced them to seek solutions to fix their “chaotic” society. If brought up prior, they may have followed suit with a primary conservative, counterEnlightenment view, but instead, “strived to find a counter balance” between the two. Thus creating the “uncomfortable mix” that Ritzer describes, forced on theorists due to the social chaos that persisted throughout Europe during the early 19th century. Much of Tocqueville’s works fit in the genre of the Enlightenment Era in the sense that he sought reformation of the current political and social systems in France, “detesting absolute systems (82).” Using his extensive research of the United States for his book, Democracy in America, he studied the U.S. model of democracy to “create a system that is democratic but structured differently (90)” to replace the current, faulted, political system in France. He believed that the French Revolution’s “principle and permanent cause was not that it was encourage by various monarch, but, rather the slow, persistent action of our institutions (93/94).” This, opposite to the conservative view, that the disruption of the traditional institutions led to the revolution, but rather the lack of change was the cause of the social disorder that pursued. Blake Huneycutt Though his ideas of reformation consisted of enlightened views, Tocqueville was still a very conservative sociologist. He was born into an aristocratic family and strongly believed that an aristocratic political system was better for the arts, creativity and overall intelligence of a society. With this view, he still praised democracy as being better for the mass populace (88), but critical (almost fearful) of governmental centralization’s perceived threat to freedom through its “both hard and soft controls over people.” He sought to reform centralized governments in order to lessen their threat to freedom (87). Tocqueville believed that “increasing equality would lead to the dangers of the concentration of power (85).” With his conservative-criticisms, he thought that as “conditions get more equal (95),” the threat of individualism would grow, causing equality to be a “cardinal sin (93).” He believed that individualism would lead people to withdraw from society, to become isolated in a materialistic society, an induce “misguided judgments (95).” Materialism was seen as a problem that would lead to a society of “servitude (96).” He even argued that the nobles, prior to the French Revolution, treated the lower class better than they were treated after (94). “Freedom was more endangered after the revolution than before because there was less centralization under the rule of the king than in post revolutionary France. Centralization under the king did not have the same power as it came to in modern governments (103).” Through his fear of modern government’s tendency to foster “equality, centralization, and loss of freedom,” Tocqueville was “firmly convinced that one couldn’t find an aristocracy in this new world, but that associations of plain citizens can compose very rich, influential and powerful, aristocratic bodies (103).” Auguste Comte, though born into a middle class family, also held both Enlightenment influence and conservative ideals about the reformation of the political and societal structure in France. He was greatly influence by the Enlightenment when he created the Law of the Three Stages, with the most important being the Positivist Stage: “people must drop nonscientific ideas, like supernatural beings and mysterious forces; instead looking for the invariable natural laws that govern all phenomena, linking them to general facts by doing empirical research and theorizing (109).” He idealistically envisioned a future that would see the elimination of theological and metaphysical thinking. He felt as though the enlightened works of his day were “incompatible” philosophies, involving all of the three stages of his laws in an incomplete and conflicting fashion, allowing for a wide variety of dangerous, “subversive schemes” to emerge, resulting in intellectual chaos and political disorder (110). He “viewed the crisis of his time as a ‘crisis of ideas’ that could only be resolved by positivism. Conservatively though, he felt that in order to create a better world, individuals must be controlled by society (114). He also felt that religion was most important institution in order to regulate individual lives and foster social relationships among people and therefore enhancing altruism within the society (116). Comte’s most counter-Enlightenment ideal, would be that the government should emphasize the good of the whole, by holding society together through force, but to prevent corruption, the governments force should be regulated by religion (117). George Ritzer statement that a mix of Enlightenment and counter-Enlightenment ideas influenced French sociologists is undeniable amongst post-revolutionary theorists. It could be argued that, if Louis de Bonald and Joseph de Maistre were born in Alexis de Tocqueville and Auguste Comte time period, that they might also be influences by the same uncomfortable mix of idea, in an attempt to amend their distorted world. All four theorists are of the conservative background, but the date of their birth is what dictates their mixture of Enlightened and counter-Enlightened views.