Organizational_Alingment

advertisement

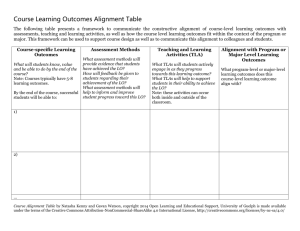

Organizational Alignment Donald Tosti INTRODUCTION The business press and academic literature are full of models for analyzing organizations and improving their performance. (Sis Sigma, Business Process Management, Culture Change, and Internal Branding are just a few examples) It is probably fair to say that all of these models can be useful for some purposes and that none of them is comprehensive. The difficulty that organizational theorists face is that an organization is a dynamic system, with multiple factors influencing performance and complex interactions between the organization and its environment as well as among components within the organization. This difficulty is analogous in some ways to the one faced by health care theorists and diagnosticians in dealing with the health of individuals. A single framework is inadequate to the task of description, diagnosis and prescription, and medical professionals use a series of models in their work. This paper takes a similar approach to organizational description, looking first at the organization as a whole and then examining it as a system with components. The result is an approach to organizational management that is comprehensive and that recognizes the need for alignment of components, both internally and with the environment. The Organization as a Whole The over-riding purpose of any organization Ð whether private or public, commercial or charitable, profit or non-profit Ð is to create value for the people who are its stakeholders. And one key to the long-term success of an organization is recognizing that its stakeholders are typically many and varied Ð e.g., owners, customers, members, employees, the community, and society at large. The first and fundamental step in organizational planning, then, is to determine what outcomes its stakeholders will value and translate these into a statement of mission and intended results that is within the organization’s scope. MISSION RESULTS ©2003-Tosti&Amarant 1 In this paper we will examine a model that improves understanding of the complexity of an organization. It is an integrated model of organizational performance that incorporates the following principles: Focuses on results and contributions to value Takes a full organizational view Provides a guiding structure to determine where improvement is need and what kinds of interventions may be most . Many people in the field of Organizational Performance use a systems model. It can be used to analyze strategy and process. It can also be used as a base for analyzing for overall organizational performance. We do this by looking at three major organizational sub systems: Organizationa l / The Management and Administration Operational / The Work People / The Job A MODEL TO LINK THE LEVELS In many ways a business organization is an ideal environment for developing a technology of performance. It is relatively self-contained; it has relatively easily measured outcomes ; it is complex enough to support the application and d evelopment of a sophisticated performance technology; and it is self -sustaining. Performance professionals quickly learned that their models which focused solely on individual performance were insufficient to permit them to improve organizational performance. An organization is a complex system. It is at its most basic level a human performance system but one which operates somewhat differently at different levels. Alignment logic allows us to analyze the relationships of components across levels. Alignment is critical to optimum performance of any complex system – an organization, the human body, or an automobile. If system components are not aligned, they cannot work together to produce optimum results. A primary management function, then, is to ensure ali gnment across levels. The Strategy Factor; aligning processes Managers often see their job as making sure that the three levels of organizational complexity are vertically aligned in the execution of a process. They do so by aligning goals and objectives with the organization’s mission statement, aligning processes with those goals in order to produce the required services/products, and finally by aligning the tasks that people perform with the pro cesses to produce results. This form of alignment is common and typically represented by the figure below. ©2003-Tosti&Amarant 2 Level Alignment Mission Organizational Goals Operational Processes Job Tasks Result Clearly then one way to improve performance is to work on any of these factors. Much progress has been made in improving processes using techniques like six sigma and BPE but those approaches still do not even come close to addressing the whole organization. When we are looking at how to strengthen performance, or solve performance problems, it is critical to consider all three levels. A large part of our analysis and intervention, however, occurs at the operational level –just as physicians focus much of their effort on the body’s functions and systems, rather than at the cell level of the body or the person as a whole. The Culture Factor: aligning practices When we look more closely at performance at the operational level, it becomes clear that results depend not just on what we do (the processes people follow) but also on how we behave as we do things (the practices people demonstrate). Even with well-designed processes, the behavioral practices of groups and individuals can make the difference between merely adequate results and outstanding results. In the worst case, poor practices can destroy good processes. Thus, what people do can sometimes be less important than how they do it, especially over the long term? Products, services and technology – even unique, first-class ones – often give organizations a short-lived edge over their competition. Sustained success depends on how an organization’s people deliver those products and services. When reengineering was first introduced as a performance intervention, many organizations spent a lot of time and money only to achieve little in the way of improved results. Follow-up studies found that in almost every case, the reason was a failure to recognize that the change in process required a re-alignment of practices for the new process to be effective. Despite this, it is only in relatively recent years that managers and performance consultants have given serious attention to practices. There appear to be at least two reasons for this: ©2003-Tosti&Amarant 3 Practices are often company -wide. In performing their jobs, most people in the organization exhibit behavior patterns that make up the “company practices.” There are prevailing norms, expectations and rewards that support these practices Ð and people whose behavior does not fit those norms and expectations may find themselves quite uncomfortable. This makes it difficult for people to change their practices unless the behavior of others around them changes at the same time and/or the environment changes in a way that clearly supports new behavior. The relationship to results may not be obvious. People usually know how their task/process behavior affects the results of their work. A good deal of effort often goes into designing processes and tasks. Practices typically develop over time, without the same kind of planning that went into process development, and may become virtually unnoticed habits. People may not see how the practices that define their approach to the work or their treatment of their co-workers affect results. For example, in some organizations a high degree of competitiveness develops that affects the way people work with other departments, as well as the w ay they view external competitors. In almost every case, the resulting working relationships are far less effective than those guided by practices that foster cooperation or partnering. But that connection is not always visible to people in the organization who are simply behaving “the same way everyone else does.” Thus if someone is asked to change task-related behaviors Ð e.g., organize information in a business case differently, or assemble equipment in a new sequence Ð the change will not usually fly in the face of prevailing norms. If someone is asked to work differently with others Ð e.g., consult widely in preparing a business case, or share equipment assembly tasks Ð it may violate expectations about how things have “always been done.” Practices can be viewed in the context of an alignment framework similar to that for processes: Level Alignment Mission Organizational Values Operational Practices Job Behaviors Results ©2003-Tosti&Amarant 4 Putting those two alignment frameworks together allows us to create a balanced model LEVEL ALIGNMENT STRATEGY/MISSION ORGANIZATIONAL GOALS VALUES OPERATIONAL PROCESSES PRACTICES JOB TASKS BEHAVIORS RESULTS ©2003-Tosti&Amarant 5 Determining Desired Strategic Processes and Cultural Practices If we are going to create a desired process we would first examine our strategy and mission to determine what results we want. Then working back from results we would define the processes that would best produce that result. The various processes would be linked to form the operations. A similar methodology would be used in determining the desired cultural practices We first examine and get agreement on desired results. Then working backs from results we would define a set of practices which would support the production of that result. These practices could then be grouped together under value labels. Let’s see how that would work Suppose we defined a desired result as “increasing customer loyalty” Then we would gather data from company employees and perhaps customers on how we should behave to deliver this result. This could be done in many ways; Surveys, card sorts, interviews, focus groups, observations etc. Now it is quite likely this research effort would indicate some practices like the following ..Always be honest: never pass on inaccurate information ..Always met your commitments ..Make sure you advice is based on fact not just your personal agenda These practices could easily be grouped under a value of “trustworthy” and then be positioned as an operational value This method is often referred to as a “criterion referenced” approach since it begins with a specific criterion; that is the desired business result and uses that as a reference point to determine what actions we should take The Power of Cultural Alignment Operational values are not just nice to have their absolutely critical if we are to deliver the desired results. This fact can also provide a strong motivation for change. The one thing we know from research on culture change is that it is most likely to occur when people in the culture see a clear advantage for that change; the most powerful advantage being to survive and/ or to thrive as a community. Since the practices are directly linked to the results of the business operational values can more easily be described as those things we must demonstrate as a company in order to survive and thrive. What's more operational values as they are derived from data from a ©2003-Tosti&Amarant 6 cross-section of employees at all levels are easier to buy into them those generated by managers at some retreat The other advantage is that operational values are derived from clustering of practices. The practices “audit in turn were derived from what was necessary to deliver results. Thus a clear trail” exists from results to practices to values. Another important factor in culture change is the ability to measure it. Since in the process of creating operational values we defined the practices; these can provide opportunities to measure present level of demonstration by the culture. Therefore the extent to which the culture is aligned with the strategy can be objectively assessed: and the “cultural gap” determined. This is a powerful tool for culture change it allows us to justifiably claim that our value alignment is not being driven by dictates of management but by dictates of the business. There are many cultural assessments instruments available in the marketplace. But virtually all of these are “norm referenced” rather than “criterion referenced”. A criterion referenced assessment is derived from an analysis of the business requirements consistent with the company’s own strategy. A norm referenced assessment is derived from a statistical analysis of some cultural dimensional theory across a wide variety of organizations with widely different strategies. Furthermore the dimensions derived from norm referenced instruments are seldom congruent with the operational values of the organization making it even harder for people to make the linkages. THE MANAGEMENT/LEADERSHIP FACTOR: Aligning Power Creating and maintaining a balanced and aligned organization requires decisions about organizational direction and intent – what the organization is in business to do, and what is important about the way it conducts its business. In addition the organization has only so much in the way of resources and those resources ideally should be allocated to maximize the success of the organization so both the leadership and the governance of the organization must be aligned to the results This is the power dimension i.e. the capacity to achieve desired results How the managers lead and govern the organization constitute another critical set of factors that must be considered in efforts to achieve results are also necessary to consider. In fact many people believe that leadership and management are the most critical influence on performance, because they have the widest impact on the organization. They represent the primary source of power in organizations. In an organizational context power can be defined as “the capacity to accomplish desired results.” Power is a positive concept when it is aligned and linked to the organizations results. Power is negative where the accomplishment only benefits a small group of people and\or is detrimental to the “health” of the organization. Although the terms of ©2003-Tosti&Amarant 7 management and leadership are far broader and richer than the definitions we have given here; in alignment we are primarily with concern with only their power aspects In alignment terms Management/ Governance Power is clearly a set of processes While Leadership Power is based on a set of practices Integration of the leadership/management function in the organizational alignment model allows us to create a comprehensive picture of organizational alignment as shown on as follows. Understanding that every organization is whole Performance System is critical for the success of virtually any attempt to improve or maintain performance. It is as important for every manager and every consultant to management to grasp this reality as it is for a medical doctor to recognize that the human body is at its basic level a biological system. Too many so called “solutions” have either failed or are short lived precisely because they have focused on process and failed to adequately address the “people and power” issues with this understanding. Using the Organizational Alignment Approach, we can develop a full systems view that allows us to identify the inter-dependency between levels of organization. It also allows us to integrate our analytical methods with our interventions This model has the potential to serve as a base that will provide a foundation for all forms of organizational consulting. The future is unlimited. REFERENCES ©2003-Tosti&Amarant 8 Brethower, D. (1972) Behavior Analysis in Business and Industry: A Total Performance System. Kalamazoo, MI: Behaviordelia Press. Gilbert, Thomas F. (1996). Human Competence, Engineering Worthy Performance. Washington, D. C.: Tribute Edition, ISPI & HRD Press. Mager, R. F. and Pipe, P. (1970). Analyzing Performance Problems. Belmont, CA: Fearon. Miller, James Grier (1978). Living Systems, New York: McGraw-Hill Rummler, Geary A. (2004). Serious Performance Consulting, According to Rummler, Silver Spring, MD: ISPI & ASTD. Tosti, D. T. and Jackson, S. F. (1994). OrganizationalAlignment: How it Works and Why it Matters. Training Magazine, April, 5 8-64. Tosti, D.T. (2009) Governance Power: Vanguard Working Paper 22 ©2003-Tosti&Amarant 9