File - E

advertisement

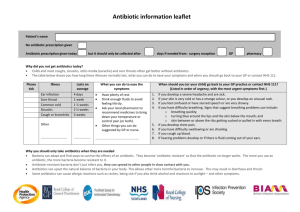

Marc Siler Antibiotic Resistance: The Microscopic Issue that is not so Microscopic Unknown to most, the issue of antibiotic resistance is one that is very serious and very dangerous. When antibiotics were first discovered, they were considered miracles and wonder drugs that helped save thousands of lives and increased the human lifespan. However, as soon as antibiotics were introduced, antibiotic resistance was already occurring and becoming an issue. Several decades later, and antibitotic resistance has been labled a ‘ticking time bomb’ and deemed one of the three biggest dangers to human health. Each year, thousands of people die, and millions more are affected due to infections from antibiotic resistance. There are people and organizations that understand that it is crucial to fight antibiotic resistance and that it is not only necessary but also vital to our society; not only health and medical organizations, but political figures as well have looked to become involved. Within the past few years, senators and representatives have lobbied congress to become more involved in the fight against antibiotic resistance, and have even proposed bills to help provide solutions for the issue. Senator Sherrod Brown proposed the Strategies to Address Antimicrobial Resistance Act on April 10, 2014. Also known as the STAAR Act (S.2236), it proposes to increase the efforts to fight antibiotic resistance through a variety of methods, which include an Antimicrobial Resistance Office, Task Force, and Advisory Board in order increase surveillance on antibiotic resistance and use. The STAAR Act is a policy that is suited to combat antibiotic resistance by focusing on certain aspects that have lacked in the current fight. The act emphasizes surveillance and understanding of the issue through an office and task force rather than solely research and development. This policy can help provide a brighter future not only within the medical field, but society as a whole. Antibiotic resistance is a complex issue, which can be attributed to multiple causes, mainly a lack of new antibiotics, misuse of drugs, and simply evolution. The years between 1950 and 1970 were labeled as a golden era of antibiotics, with multiple new drug classes and antibiotics being discovered and produced. Yet since then, there has been a severe decrease in the development of new antibiotics. This can be attributed to pharmaceutical companies severely cutting back funding on their research and development programs or just stopping completely. For these companies, the costs of looking for new antibiotics outweigh the benefits, and do not provide a great return on their investment. Drug misuse only compounds that issue. Common forms of drug misuse are using antibiotics for sicknesses they cannot treat, or not taking the drugs as prescribed. If an antibiotic is used to treat a viral infection, there is no benefit and the drugs lose effectiveness against bacteria. Likewise, if a person were to take antibiotics for a shorter period than prescribed, all the bacteria may not be gone, and the surviving will develop resistance and spread to infect others. Also, bacteria have existed since arguable the existence of Earth, and antibiotics haven’t even been discovered for over a century. Bacteria have figured ways to survive and thrive in various conditions, becoming resistant to antibiotics is part of that. Antibiotic resistance is not something that can be completely stopped, but it can be slowed and infections can be prevented. The decline in developing new antibiotics due to the decrease in research and funding from pharmaceutical companies is a factor that has been pointed out by many involved within the issue of antibiotic resistance. So why not increase research and development programs from pharmaceutical companies and hopefully produce new antibiotics? The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) looks to accomplish just that, with their implement of the 10 x ’20 (ten by twenty) Initiative. According to the IDSA, their goal is to have 10 new antibiotics produced by the year 2020. However, this is easier said than done. It would be difficult to persuade various companies to commit to re-funding their research and development programs. Addressing only one aspect of the issue is not the most effective approach, but rather a policy that acknowledges all contributing factors of antibiotic resistance. As noted earlier, the main causes of antibiotic resistance are: the lack of development of new antibiotics, overprescription of drugs, drug misuse, and limited understanding of the issue. We must understand the complexity and the depth of the issue at hand. Without it, all efforts will be unsuccessful. This is what the STAAR Act looks to accomplish. The goals of the STAAR Act are to promote prevention, track resistant bacteria, improve the use of antibiotics, and enhance leadership and coordination in addition to supporting research. The STAAR act looks to accomplish this by increasing surveillance on the use of antibiotics and the infections caused by antibiotic resistance, establishing and Antibiotic office, task force, and advisory board, and creating a more strategic research plan. The main purpose of this policy is the establishment of the Antimicrobial resistance office, antimicrobial resistance task force, and the Public Health Antimicrobial Advisory Board. The task force is to be composed of the Antimicrobial resistance office and representatives from 15 organizations and departments, including the Department of Defense, the Centers for Disease Control and Preventions, and the Department of Homeland Security, amongst others. Collectively, all three groups will have a variety of responsibilities: 1. Intensify and expand their efforts to collect antimicrobial resistance data and assess the ongoing, observed patterns of emergence of antimicrobial resistance i. Monitor the changes in the patterns of antimicrobial resistant pathogens ii. Recommend how best to strengthen antimicrobial resistance-related surveillance and prevention iii. Collect surveillance data regarding emerging antimicrobial resistance from reliable sources including the CDC 2. Collect data on the amount of antimicrobial products used in humans from reliable sources, including data from the CDC i. Provide ways to encourage the availability of an adequate supply of safe and effective antimicrobial products, 3. Facilitate research to better understand resistance mechanisms and how to prevent, control, and treat resistant organism 4. Establish a list that prioritizes diseases based on the greatest need for the development new drugs, especially those that are particularly serious and life-threatening and have few treatment options 5. Provide reports of federally supported antimicrobial resistance research and antimicrobial drug development for antimicrobial resistant infections (S.2236) Senator Brown understands the need to develop a fuller understanding of this issue, and ensures that focus within the policy. This is because the Center for Disease Control and Prevention released a report in 2013, and stated that there is a inadequate knowledge in the understanding of antibiotic resistance because of the “limited national, state, and federal capacity to detect…urgent and emerging antibiotic resistant threats”, “no systematic surveillance of antibiotic resistance threats”, and “data on antibiotic use in human healthcare…are not systematically collected” (CDC). That will hopefully change if the STAAR Act were to pass. In fact, the terms ‘surveillance’ and ‘data’ are used approximately 50 times total. That just goes to show how committed this policy is in looking to fight antibiotic resistance in ways other than only research and development programs. The STAAR Act proposes the use of an Antibiotic office, task force, and board that would incorporate surveillance and collect data, but this does not come without costs. The proposal asks for “$100,000,000 annually for each of fiscal years 2015 through 2021 to carry out this [policy]” (S.2236). If implemented, the policy would cost approximately $600 million if they stay within budget. At first glance, $600 million appears to be an extreme amount of money, however, relative to the financial burden that antibiotic resistance is currently costing, it is less than one-eighth of what it being spent to treat infections caused by antibiotic resistant bacteria. People that are infected by a resistant pathogen require longer hospital stays and more expensive drugs, leading to increased costs in health care. And with over 2 million people affected by resistant bacteria, the costs definitely adds up. In fact, it adds up to over $5 billion, annually (Bad Bugs, No Drugs). In order to perspective of how prevalent of an issue antibiotic resistance is, just two decades ago, $1.3 billion was spent to treat those infected by resistant bacteria (Aminov). That is a 284% increase, and it will continue to increase if nothing new is done to slow antibiotic resistance. It was stated earlier that new research and development programs would cost anywhere from $800 million to $1.7 billion (Bad Bugs, No Drugs). The STAAR Act is likely cheaper and likely more effective. While the financial costs of the policy are explicitly stated, the other costs are not. The introduction of the new Antibiotic Task Force and Office is something new. It is unknown if they will be successful or effective in helping to combat antibiotic resistance. If they are not, then the policy would cost us five or six years of time. It is also unknown how much worse the issue of antibiotic resistance can become. In five or six years, there will be more ‘superbugs’ and more deaths. If the policy fails, it could also discourage further federal involvement within this issue. The social, medical, and political costs have the risk to be substantial. Yet what the STAAR Act looks to accomplish has the potential to be enormous, finally gaining an understanding of antibiotic resistance, hopefully decreasing the rate of infections, decreasing drug misuse, and ultimately, saving lives. If the act is successful and effective, the potential benefits outweigh the risks of the costs. Although the STAAR Act looks to accomplish many things all at the same time and appears to be a task that is a bit too ambitious, implementation of the policy is one that is feasible. There are already numerous organizations working to combat antibiotic resistance, but with the STAAR Act, many organizations can work together with leadership and develop a direction to create a more organized and effective fight. Employing the policy will not go without bumps in the road. A large part of the act relies on submission and collection of data, but initially that could be an issue. This requires that hospitals and doctors comply in reporting their data to the appointed task office. In an interview by Innovations Exchange Team of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (U.S Department of Health & Human Services), Dr. Edward J. Septimus states that the main “challenge is getting doctors to commit to spending the time that’s required. The IDSA confirms that statement because they recognize that “reporting data…is an extra, ‘onerous’ activity for hospitals,” (IDSA) and that it may be necessary to incorporate a plan that presents incentives ensuring participation and commitment from the hospitals to make that time and effort in reporting antibiotic consumption and resistance data. Yet this issue has not been overlook by Brown, and included in the policy that “incentives (are) necessary to establish uniform mechanisms and date sets for…reporting of resistance” (S.2236). Incentives may be the only way to persuade these hospitals and doctors report data. In Atul Gawande’s Better, it’s told that a decade or so ago, that it was an issue with doctors taking the time to wash their hands, which is a basic, yet crucial exercise. If doctors are unable to spend time washing their hands, how can we rely on them to report data? Doctors should understand that antibiotic-resistance infections have typically been hospital-acquired. Therefore, the issue in implementing this policy will not be ignorance, but it will be compliance. In order for the policy to be successful, it will require a collective group effort from everyone, not just the office or the task force or the advisory board. If that can happen, the policy is definitely feasible and possible. It’s unknown how catastrophic the consequences of ineffective antibiotics can be, but we are not far away from finding out. Our society is dangerously close to having to survive without being able to rely on antibiotics. If no action is taken, it is likely that we enter a post-antibiotic era. That means that some of the most common infections or smallest of cuts can kill. That’s a scary thought. Imagine a child, being a son/daughter or little bother/sister, falling and scraping a knee, becoming infected and there being no options for treatment. It’s sad and unfortunate, but it’s a scenario that’s likely in the near future. Congress needs to understand the urgency of this issue and the need to implement the STAAR act. Many people do not know what its like to live with out antibiotics, and I’m sure many do not want to know what that life is like. The need for the STAAR Act is real. The time is now. Reflection What was most difficult about writing this draft? Collecting all my thoughts into one paper. There was so much research conducted this quarter that I was able to understand how I wanted to organize this paper and what I wanted to include. Yet, it was being able to actually type everything that I wanted to include and being able to construct a paper that still flowed and fulfilled the purpose. What did you work hardest on? I feel like I worked hardest on trying to establish the urgency of the issue. Antibiotic resistance isn’t a well-known issue or as commercialized as things like cancer and diabetes, yet it poses a far greater risk. I wanted to establish that urgency without losing focus on the prompt. What do you think still needs the most work? The alternative policy needs the most work. It’s hard to discuss the strengths of a policy when your focus of the paper is to advocate for a different policy. I’m able to refute the alternative without much trouble, but I need to focus on why that alternative policy is somewhat plausible. What would you like me to focus on when commenting? Challenge my ideas. Act as a devil’s advocate in a sense, because I want people to be able to understand how important of an issue this is and why my policy works. If certain things do not make sense, or can be refuted, point it out so I can challenge it or find an alternative way to present certain ideas. Bibliography Antibiotic Resistance Threats. Rep. Center for Disease Control and Prevention, n.d. Web. <http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/threat-report-2013/pdf/ar-threats-2013508.pdf>. Bad Bugs, No Drugs. Rep. N.p.: n.p., n.d. Infectious Diseases Society of America, July 2004. Web. 13 Apr. 2014. <http://www.idsociety.org/uploadedfiles/idsa/policy_and_advocacy/current_topic s_and_issues/antimicrobial_resistance/10x20/images/bad%20bugs%20no%20dru gs.pdf>. Boucher, H. W., G. H. Talbot, D. K. Benjamin, J. Bradley, R. J. Guidos, R. N. Jones, B. E. Murray, R. A. Bonomo, and D. Gilbert. "10 X '20 Progress--Development of New Drugs Active Against Gram-Negative Bacilli: An Update From the Infectious Diseases Society of America."Clinical Infectious Diseases 56.12 (2013): 1685-694. Oxford Journals. Web. 14 May 2014. "Combating Antimicrobial Resistance: Policy Recommendations to Save Lives." Clinical Infectious Diseases 52.Supplement 5 (2011): S397-428.Clinical Infectious Diseases. Oxford Journals. Web. 8 May 2014. Fernandes, Prabhavathi, and Mariagrazia Pizza. "Addressing the Frustrations of Finding New Effective Antibacterials to Combat Drug Resistant Bacteria." Current Opinion in Microbiology 11.5 (2008): 385-86.PubMed. Web. 15 May 2014. Outterson, Kevin, John H. Powers, Ian M. Gould, and Aaron S. Kesselheim. "Questions about the 10 × ‘20 Initiative." Clinical Infectious Diseases51.6 (2010): 751-52. PubMed. Web. 13 May 2014. Septimus, Edward J. "Antimicrobial Resistance Still Poses a Public Health Threat." Interview by AHRQ Innovations Exchange Team. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. United States Department of Health and Human Services, n.d. Web. 10 May 2014. Strategies to Address Antimicrobial Resistance, S. 2236, 113th Cong. (2014). Print. "The 10 × ‘20 Initiative: Pursuing a Global Commitment to Develop 10 New Antibacterial Drugs by 2020." Clinical Infectious Diseases 50.8 (2010): 1081-083. Clinical Infectious Diseases. Oxford Journals, 19 Feb. 2010. Web. 7 May 2014. Tillotson, Glenn S. "Development of New Antibacterials: A Laudable Aim, But What Is the Value?" Clinical Infectious Diseases 51.6 (2010): 752-53. Oxford Journals. Web. 14 May 2014. Wattal, Chand. "Development of Antibiotic Resistance and Its Audit in Our Country: How to Develop an Antibiotic Policy." Indian Journal of Medical Microbiology 30.4 (2012): 381. Academic Search Complete. Web. 16 May 2014.