Thornton Briana Thornton English 301 Professor Basu Decoding the

advertisement

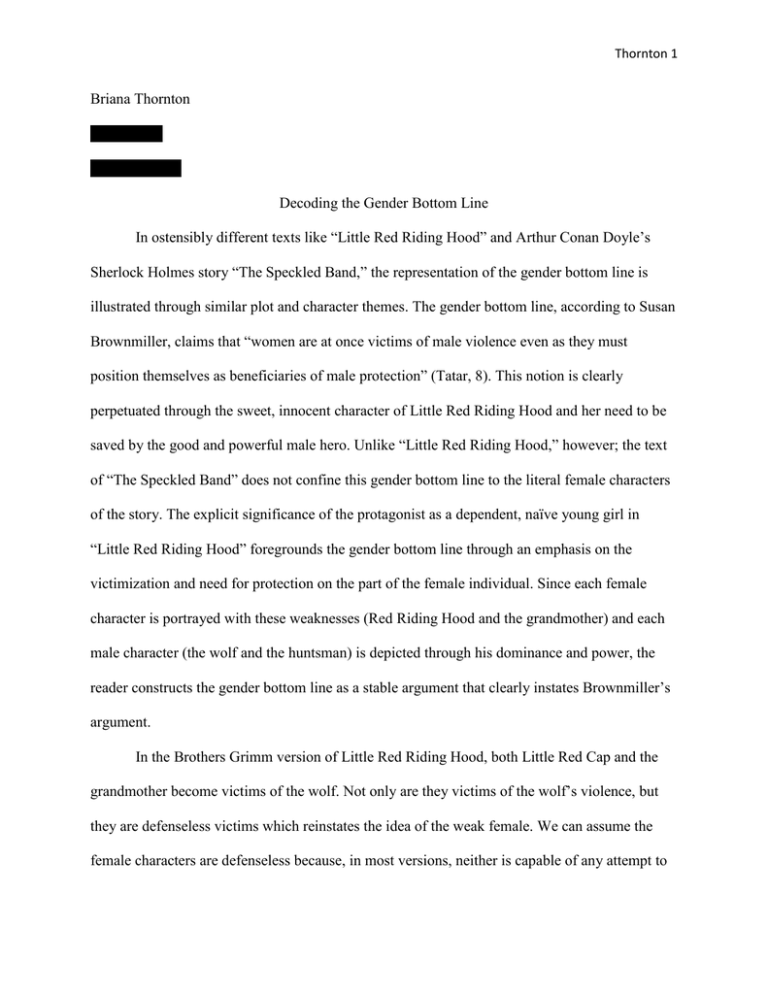

Thornton 1 Briana Thornton English 301 Professor Basu Decoding the Gender Bottom Line In ostensibly different texts like “Little Red Riding Hood” and Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes story “The Speckled Band,” the representation of the gender bottom line is illustrated through similar plot and character themes. The gender bottom line, according to Susan Brownmiller, claims that “women are at once victims of male violence even as they must position themselves as beneficiaries of male protection” (Tatar, 8). This notion is clearly perpetuated through the sweet, innocent character of Little Red Riding Hood and her need to be saved by the good and powerful male hero. Unlike “Little Red Riding Hood,” however; the text of “The Speckled Band” does not confine this gender bottom line to the literal female characters of the story. The explicit significance of the protagonist as a dependent, naïve young girl in “Little Red Riding Hood” foregrounds the gender bottom line through an emphasis on the victimization and need for protection on the part of the female individual. Since each female character is portrayed with these weaknesses (Red Riding Hood and the grandmother) and each male character (the wolf and the huntsman) is depicted through his dominance and power, the reader constructs the gender bottom line as a stable argument that clearly instates Brownmiller’s argument. In the Brothers Grimm version of Little Red Riding Hood, both Little Red Cap and the grandmother become victims of the wolf. Not only are they victims of the wolf’s violence, but they are defenseless victims which reinstates the idea of the weak female. We can assume the female characters are defenseless because, in most versions, neither is capable of any attempt to Thornton 2 escape the wolf, and they are both forced to rely on another male character, the huntsman, to save them from the wolf’s stomach. As soon as the wolf had “satisfied his desires,” the huntsman is immediately introduced as a means to save the female victims (Tatar, 15). The female characters are now directly shifted from the victims to the helpless, dependent damsels in distress, allowing no time or possibility for either of them to be identified as anything else. In this particular version, the masculinity of the wolf and the huntsman exemplifies Brownmiller’s claim regarding the gender bottom line, not only identifying women as victims and dependents, but by identifying men as either protectors or adversaries. In the version of Little Red Riding Hood titled “The Story of Grandmother,” the female protagonist is once again represented as the victim; however, she becomes not only a victim of physical violence, but a victim of sexual violence as well. In this version, the child is instructed by the wolf to take off her clothes and climb into bed with him. Then, “When she asked the wolf where to put all her other things, her bodice, her dress, her skirt, and her stockings, each time he said: ‘Throw them into the fire, my child. You won’t be needing them any longer’” (Tatar, 11). While the act of sex is not explicitly rendered during this scene, it is evident through this text that Red Riding Hood has become victimized by the male character by being sexualized. The actions that take place in this scene are described in a slow, almost leisurely manner which creates the illusion of a strip tease. By obeying the wolf’s commands and falling willingly into this portrayal, the girl becomes subject to his authority and allows her sexuality to eliminate her own agency. Some may argue that because Little Red Riding is willing to fall into a submissive role that she does have agency and, therefore, breaks the gender bottom line. Others can argue as I do, however, that this willingness is not a choice, but rather a need for survival. Red Riding Hood only performs the “strip tease” in order to escape from the villain. This is proven in the end Thornton 3 of the story when Red Riding Hood frees herself from the rope and runs home towards safety (Tatar, 11). Her desire to escape reinstates her position as the victim and diminishes any real free will she potentially could have had. In regards to the context of fairy tales, the gender bottom line is easily exposed in these stories because of their highly common plot, characters, and themes. This is not the only genre, however, that is capable of establishing a gender bottom line within its text. Although slightly more ambiguous, Arthur Conan Doyle’s detective series of Sherlock Holmes establishes a gender bottom line that is commensurate with Brownmiller’s argument regarding the problem in “Little Red Riding Hood.” This can be seen in the Sherlock Holmes story of “The Speckled Band” which contains analogous concepts previously mentioned in the various Red Riding Hood tales. In this story, a young woman named Helen Stoner employs Sherlock Holmes and Watson to investigate the death of her sister, Julia. During this time, Helen lives with her ill-mannered step-father Grimesby Roylott and is to be married soon which will enable her to inherit the money which her deceased mother has left her. Throughout the case, Holmes becomes suspicious of the seemingly villainous step-father and soon finds out that he is, in fact, not only responsible for Julia’s death, but of the attempt on Helen’s life as well. The main female character of the story, Helen, is distinguished by traits similar to those of Red Riding Hood, including her need for protection and her weak femininity which easily falls prey to male violence. A major motif presented throughout the story that demonstrates this claim is the idea of women as property. According to Rosemary Hennessy and Rajeswari Mohan, “Helen, poised ambiguously between the conditions of property and property owner, cannot be granted her independence, of speech any more than of capitalistic or social status” (Hodgson, 389). This argument recognizes Helen’s identification as property because of her dependence on male Thornton 4 characters, the first of which is her stepfather and the second her soon to be husband. With this type of societal position, Helen is unable to escape the oppression of patriarchal representatives. The claim that Helen’s independence of speech is eradicated because of her social status and objectification is established in the story when she chooses not to disclose the entire truth about Roylott. Holmes reveals to Helen that she is “screening [her] stepfather” and has “been cruelly used” (Hodgson, 159). After observing this scene, it is evident that Helen’s speech and actions, or lack thereof, are greatly influenced and hindered by the patriarchal position of Roylott. Because of her stepfather’s overbearing power, Helen, like Red Riding Hood, becomes victimized by male authority and forced to depend on this same authority to escape further victimization. Also commensurate with Brownmiller’s argument of the gender bottom line, is Helen’s need to be protected by the masculine figure. While Helen becomes victim to Roylott as Red Riding Hood falls victim to the wolf, Helen also depends on Sherlock Holmes to save her as the huntsman saves Red Riding Hood. In this context, although still a patriarchal figure, Holmes is identified as the hero of the story. According to Hennessy and Mohan, “[The story] presents Holmes as woman’s protector, rescuing her from the villainous patriarch’s domination and defending her right to control over her own property and person” (Hodgson, 390). The reader assumes Holmes position as protector because Helen depends on him to solve her sister’s murder and save her from experiencing the same horrid fate. Although Holmes is labeled the protector throughout the story for these reasons, it can be argued that he is merely a manager who successfully contains the possibility of Helen becoming an independent woman. Holmes takes on this managerial position by creating a solution that serves the purpose of expediting Helen’s swift transition from daughter to wife (Hodgson, 390). By detaining Helen within these two Thornton 5 spheres, Holmes is removing her from one male patriarch just to place her in the possession of another. In regards to this argument, therefore, Holmes can serve as the woman’s protector, but Helen will not escape being a victim of male patriarchy because Holmes will not allow it. Since Holmes manages Helen’s position throughout the story, he becomes the most influential male figure. Therefore, although slightly deceiving, Holmes does not oppose traditional patriarchal domination, but merely represents a “new” type of patriarchy. In other words, as Hennessy and Mohan state, “this ‘newness’ is more a re-articulation than a transformation of the sexual economy of patriarchy” (Hodgson, 395). To better understand this re-articulation, it is helpful to observe the social relations taking place during this time period. With the rise of the Industrial Revolution also came the rise of a new professionalized middle class. At the same time, the aristocracy is falling which gives way for the emergence of a new patriarchal figure. In “The Speckled Band,” Holmes, as a middle-class restrained gentleman, represents this figure. Roylott, on the other hand, is representative of the failing aristocracy because of the apparent dissipation in his wealth. To add even more to these social relations, Holmes’ method is closely tied to the workings of the State. Through acts such as the Married Woman’s Property Act which “[gave] women control over their property; but by doing so in term of male protection” and the Criminal Law Amendment Act which “[affected] the status of woman outside the home in raising the age of consent for girls from 13 to 16,” it appears women are given more rights when in actuality, their positions are merely being readjusted by the State. Such as Holmes readjusts the position of Helen from recipient of her step-father’s protection to recipient of the fiancé’s protection, the State serves as the same patriarchal figure towards women. Through this analogy, Brownmiller’s claim on the gender-bottom line holds true and contains any potential threat to it. Thornton 6 Another way that Holmes is presented as the protector in this story is by being juxtaposed with the reverse character of Roylott through geographical means. In order to construct Holmes as the hero, “the narrative draws upon the codes of otherness such as irrationality, lack of control, and dissipation, set by the discourses of alterity” (Hodgson, 390). While Holmes is presented as Western, rational, and positioned within the middle/upper class, Roylott is given contracting characteristics in order to highlight him as the “other” within the narrative. This is displayed through the multiple, outlandish traits that Roylott is given throughout the progress of the story. The first instance the reader is exposed to his otherness is when Helen describes to Holmes the terrible change that has come over her stepfather. “Violence of temper approaching to mania has been hereditary in the men of the family, and in my stepfather’s case it had, I believe, been intensified by his long residence in the tropics” (Hodgson, 155). The prominent characteristic revealed in this passage is Roylott’s irrationality which is immediately presented in opposition to the rational being of Sherlock Holmes. His temper serves as a mark of his otherness, as well as his weakness. A more ambiguous trait that is noteworthy in this passage, however, is the recognition of Roylott as being a former resident of the tropics. Whereas Holmes is obviously declared to be of Western origins, the identification of Roylott as an Eastern character immediately places him within the realm of the other. This classification remains with Roylott throughout the entirety of the story as more of his Eastern mannerisms are revealed such as his association with gypsies and his interest in exotic animals. It is precisely this privileging of the Western patriarch over the Eastern man that enables the crisis of the patriarchal alliance to gain its global and colonial scale. Also, as Hennessy and Mohan point out, because of Holmes’s position in the narrative as subject of knowledge, the reader is able to identify with his character, Thornton 7 therefore, dissociating him from any possible connections to imperial domination, patriarchal control, and class privilege (Hodgson, 392). In relation to the aforementioned argument of the gender bottom line, because of his identification as the other, Roylott becomes a victim of the gender bottom line in a manner similar to Helen and Red Riding Hood’s. According to Hennessey and Mohan, “The entangled coding of the feminine and the Oriental as sexualized other in the Holmes story is an instance of the ways the sexualization of woman and Oriental male re-secured patriarchal and imperial interests across a range of class positions” (Hodgson, 400). One claim that this particular section draws upon is Roylott’s social status as part of the declining aristocracy. As previously mentioned, Roylott is thus a ‘failing’ man in relation to members of the professional and middle class such as Holmes, who have greatly developed during this time period. This connection to the global, social crisis places Roylott in a dependent role that female characters such as Helen and Red Riding Hood are constantly found in. Since women, in general, were also identified as a type of “other” in society, it is reasonable to assume that the similarities between Roylott and Helen are developed to set them both apart from Holmes. For instance, both characters are given animalistic characteristics such as Helen’s “restless, frightened eyes, like those of some hunted animal” (Hodgson, 153) and Roylott’s likeness to a “fierce old bird of prey” (Hodgson, 161). They are both sexualized in some way as well since Helen’s female body serves as a symbolic ground for woman’s contradictory position as property and property owner, and Roylott is characterized as a sexual offender by his patriarchal position and his association with phallic objects like the cane and the snake. This type of sexual victimization relates back to the sexual violence in versions of “Little Red Riding Hood” such as “The Story of Grandmother” and how the sexuality of woman forces them into the gender bottom line. This textual evidence can be Thornton 8 used to argue that, although a male character, Roylott is given a type of femininity that allows him to fall victim to the gender bottom line. In tales such as “Little Red Riding Hood,” we only see this concept in regards to the literal female characters of the story; for instance, the little girl and the grandmother, but by expanding this notion onto a male character, “The Speckled Band” reinforces this claim in an unconventional way that gives the gender bottom line an even greater influence.