sepawa m 14 warren 01

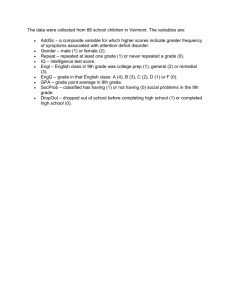

JUDICIAL REVIEW UNDER NEPA

Colleen G. Warren

Law Seminars International

NEPA/SEPA CLE

January 25, 2006

OUTLINE OF PRESENTATION

2

I.

II.

III.

IV.

V.

STANDING

STANDARD OF REVIEW

SCOPE OF REVIEW

INJUNCTIONS

STATUTE OF LIMITATIONS

3

I.

STANDING

“ Where the party does not rely on any specific statute authorizing invocation of the judicial process, the question of standing depends upon whether the party has alleged such a ‘personal stake in the outcome of the controversy’ as to ensure that ‘the dispute sought to be adjudicated will be presented in an adversary context and in a form historically viewed as capable of judicial resolution . . .”

Sierra Club v. Morton , 405 U.S. 727 (1972)

4

A.

Constitutional Standing

Requirements -- Article III

To satisfy Article III standing requirements under the

U.S. Constitution, a plaintiff must show that: (1) it has suffered an “injury in fact” that is (a) concrete and particularized and (b) actual or imminent, not conjectural or hypothetical; (2) the injury is fairly traceable to the challenged action of the defendant; and (3) it is likely, as opposed to merely speculative, that the injury will be redressed by a favorable decision.” Cantrell v. City of Long Beach, 241 F.3d

674, 679 (9 th Cir. 2001)

5

1. Injury in Fact a. Concrete & Particularized ii. General Interest

“[T]he ‘injury in fact’ test requires more than an injury to a cognizable interest. It requires that the party seeking review be himself among the injured.” Sierra

Club v. Morton , 405 U.S. 727 (1972)(alleged injury directly felt only by those who use Mineral King and

Sequoia National Park for recreation or aesthetic values; Sierra Club failed to allege that it or its members would be affected in any of their activities or pastimes by the Disney Development)

1. Injury in Fact a. Concrete & Particularized ii. Aesthetic/Recreational Interest

6

Injury in Fact standing requirement shown if plaintiff shows an “aesthetic or recreational interest in a particular place, or animal or plant species and that interest is impaired by a defendant’s conduct.”

Ecological Rights Foundation v. Pacific Lumber Co.,

230 F.3d 1141 (9 th Cir. 2000)

Plaintiff need not live nearby to establish a concrete injury. “Repeated recreational use itself, accompanied by a credible allegation of desired future use, can be sufficient even if relatively infrequent, to demonstrate that environmental degradation of the area is injurious to that person. Id .

7

1. Injury in Fact b. Actual or Imminent

While the personal injury requirement will be met only if the alleged harm is “distinct and palpable . . . and not abstract or conjectural or hypothetical” Allen v. Wright, 468 U.S.

737 (984), failure to follow procedures designed to ensure that the environmental consequences of a project are adequately evaluated is a sufficient injury. Friends of the

Earth v. U.S. Navy, 841 F.2d 927, 931 (9 th

Cir. 1988)

8

2

. Causation

To establish causation, the injury must be

"fairly traceable to the challenged action of the defendant[,]" Friends of the Earth v.

Laidlaw Environmental Services, 528 U.S.

167, 180, and cannot be the result of the

"independent action of some third party not before the court." Sierra Club v. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 235 F.Supp.2d 1109,

1122 (D.Or. 2002)

9

2

. Redressability

The injury must be "fairly" traceable to the challenged action, and relief from the injury must be

"likely" to follow from a favorable decision. Allen V.

Wright, 468 U.S. 737, 751 (1984). However, a plaintiff asserting inadequacy of government agency’s environmental studies need not show that further analysis would result in a different conclusion.

It suffices that agency’s decision could be influenced by environmental considerations that NEPA requires an agency to study. Ocean Advocates v. U.S. Army

Corps of Engr’s, 402 F.3d 846 880 (9 th Cir. 2005)

10

B. APA Standing Requirements

(5 U.S.C. § 702)

A NEPA challenge must also meet the standing requirements for review under the APA which require a plaintiff to:

(1) Identify some agency action that adversely affects the plaintiff, and

(2) establish that he/she has suffered legal wrong because of the challenged agency action or is adversely affected or aggrieved by that action within the meaning of a relevant statute.

11

1. Final Agency Action

When judicial review of agency action is sought, not pursuant to specific authorization in substantive statute, but only under general review provisions of the APA, the “agency action” must be final agency action. 5 U.S.C.

§ 704; Lujan v. National Wildlife Fed., 497

U.S. 871 (1990)(organization failed to identify any particular agency action that was the source of the alleged injury to its members)

12

2. Adversely Affected or Aggrieved

To be adversely affected or aggrieved for purposes of obtaining judicial review of agency action under the APA, a plaintiff must establish that the injury complained of (the aggrievement, or the adverse effect) falls within the “ zone of interests ” sought to be protected by the statutory provision whose violation forms the legal basis for his complaint. Lujan v. National Wildlife

Federation , 497 U.S. 871 (1990).

2. Adversely Affected or Aggrieved

(cont’d)

13

The “zone of interests” test helps to ensure that only those suits that would further the statutory objectives are allowed, and those that would frustrate it are halted. Clarke v.

Securities Indus. Ass’n, 479 U.S. 388, 397 n.

12 (1987)

This test is not meant to be especially demanding. Plaintiff need only show that its interests share a “plausible relationship” to the policies underlying each statute. Ocean

Advocates v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers ,

402 F.3d 846 (9 th Cir. 2005)

14

2. Adversely Affected or Aggrieved

(cont’d)

Purpose of NEPA is to protect the environment, not economic interests. Therefore, a plaintiff who asserts purely economic injuries does not have standing to challenge an agency action under NEPA.

Nevada Land Assoc. v. U.S. Forest Service, 8 F.3d

713, 716 (9 TH Cir.1993). See also, Kanoa, Inc. v.

Clinton , 1 F.Supp.2d 1088 (1988) (plaintiff did not assert environmental injury, but alleged only economic injury resulting from disruption of its business and thus did not establish standing under the APA)

15

C.

Associational Standing

A membership organization can sue in its representative capacity when: (1) its members would otherwise have standing to sue in their own right; (2) the interests the organization seeks to protect are germane to the organization’s purpose; and (3) neither the claim asserted nor the relief requested requires the participation of individual members in the lawsuit. Presidio Golf Club v. Nat’l

Park Serv., 155 F.3d 1153 (9 th Cir. 1998)

16

II.

STANDARD OF REVIEW

“The National Environmental Policy Act of 1969

(“NEPA”) is a procedural statute designed to ensure that federal agencies taking major actions affecting the quality of the human environment ‘will not act on incomplete information, only to regret its decision after it is too late.’”

Sierra Club v. Bosworth , 2005 WL 3096149 (N.D.

Cal. 2005), quoting Marsh v. Oregon Natural

Resources Council, 490 U.S. 360, 371 (1989).

17

A.

Rule of Reason Standard

The Ninth Circuit reviews NEPA documents under the “rule of reason” standard.

Court inquires as to: (1) whether a document contains a reasonably thorough discussion of the significant aspects of the probable environmental consequences; and (2) whether the document’s form, content and preparation foster both informed decision-making and informed public participation.

See Klamath-Siskiyou Wildlands Ctr. V. Bureau of

Land Mgmt.

, 387 F.3d 989 (9 th Cir.2004)

18

B.

Arbitrary and Capricious

Standard

A review of factual disputes requires the application of the arbitrary and capricious standard. Greenpeace Action v.

Franklin, 14 F.3d 1324, 1331 (9 th Cir.1992)

The court reviews the decision to determine whether the agency “considered the relevant factors and articulated a rational connection between the facts found and the choice made.” Pacific Coast Fed’n of Fisherman Ass’ns v. NMFS , 265

F.3d 1028, 1034 (9 th Cir.2001)

Ultimately, “the standard of review is a narrow one. The court is not empowered to substitute its judgment for that of the agency.” Arizona Cattle Growers’ Ass’n v. U.S. Fish & Wildlife

Serv.

, 273 F.3d 1229, 1236 (9 th Cir.2001)

C.

Two Tests Not Materially Different

19

Several circuits, including the Ninth Circuit, have held that “the rule of reason review” is not materially different from the "arbitrary and capricious" standard in cases involving NEPA. The Lands Council v.

Powell , 379 F.3d 738,743 n. 5 (9th Cir.2004); League of Wilderness Defenders-Blue Mountains

Biodiversity Project v. U.S. Forest Service , 2004 WL

2642705 (D.Or. 2004)

Under either standard, the goal is to ensure that the agency has taken a "hard look" at the potential environmental consequences of the proposed action.

Churchill County v. Norton , 276 F.3d 1060,1072 (9 th

Cir. 2001)

20

III. SCOPE OF REVIEW

“[T]he focal point for judicial review should be the administrative record already in existence, not some new record made initially in the reviewing court.”

Florida Power & Light Co. v. Lorion , 470 U.S.

729 (1985).

21

A.

Limited to Administrative Record

Generally, judicial review of agency action is limited to review of the administrative record.

Friends of the Earth v. Hintz, 800 F.2d 822

(9 th Cir.1986)

Standard applicable to review of agency action under NEPA. Id.

at 829.

22

B.

Exceptions

1.

Where necessary to explain the agency’s action;

2.

To determine whether the agency has considered all relevant factors or has explained its course of conduct or grounds of decision

3.

When agency relied on documents not in record;

4.

When necessary to explain technical terms or complex subject matter; and

5.

When showing of agency bad faith

See Animal Defense Council v. Hodel, 840 F.2d

1432 (9 th Cir.1988)

23

C.

Broader Scope of Review For

Agency Inaction

While judicial review of agency action is generally limited to review of the administrative record, where the issue is alleged agency inaction the scope of review “is broader, particularly where the issue is whether an agency’s activities have triggered NEPA procedures. A broader scope of review is necessary because there will generally be little, if any, record to review.” Northcoast Environmental Center v.

Glickman , 136 F.3d 660 (9 th Cir.1998)

24

D.

New Evidence in Challenge to EIS

“[T]he district court may extend its review beyond the administrative record and permit the introduction of new evidence in NEPA cases where the plaintiff alleges ‘that an EIS has neglected to mention a serious environmental consequence, failed adequately to discuss some reasonable alternative, or otherwise swept ‘stubborn problems or serious criticism . . . under the rug.’” (See Animal Defense

Council v. Hodel, 840 F.2d 1432 (9 th Cir. 1988)

(quoting County of Suffolk v. Secretary of the Interior,

562 F.2d 1368 (2d Cir.1977)

25

E.

Cases Allowing Supplementation of Agency Record

GreenPeace v. Evans , 688 F.Supp. 579 (W.D. Wash. 1987)

( allowing zoologist’s declaration on the basis that it “assists the court in concluding that NMFS did not adequately consider the risks of long term adverse impacts on the killer whale population of Puget Sound.” )

Citizens for Environmental Quality v. U.S., 731 F.Supp. 970

(D.Col. 1989)(affidavits of experts on the use of computer models and forest planning relating to decision to issue a comprehensive land resource forest management plan were admissible where affidavits were helpful to the court's understanding of complex issues presented by the case, illuminated information contained in the administrative record, and served as points of reference therein)

26

F.

Cases Limiting Judicial Review to the Agency Record

Friends of the Earth v. Hintz , 800 F.2d 822

(9 th Cir. 1986) (district court’s decision quashing plaintiffs deposition notices upheld on appeal)

Havasupai Tribe v. Robertson , 943 F.2d 32

(9th Cir. 1991) (denying tribes request for discovery because it’s claim that agency considered evidence beyond the administrative record is purely speculative)

27

IV. INJUNCTIVE RELIEF

The standard for granting a preliminary injunction balances the plaintiff’s likelihood of success against the relative hardship to the parties.

Clear Channel Outdoor, Inc. v. City of Los

Angeles, 340 F.3d 810 (9 th Cir.2003)

28

A.

Standards for Injunctive Relief

The Ninth Circuit has recognized two different sets of criteria for injunctive relief:

(1) the traditional criteria; and

(2) the alternative criteria

Save Our Sonoran, Inc. v. Flowers , 408 F.3d 1113

(9 th Cir. 2005)

29

B.

Traditional Criteria

Plaintiff must show:

(1) a strong likelihood of success on the merits

(2) the possibility of irreparable injury to plaintiff if preliminary relief is not granted

(3) a balance of hardships favoring plaintiff

(4) advancement of the public interest (in certain cases)

30

C.

Alternative Criteria

Plaintiff must show either:

(1) either a combination of probable success on the merits and the possibility of irreparable injury; or

(2) that serious questions are raised and the balance of hardships tips sharply in there favor

31

D.

Injunctive Relief under These

Criteria are not Separate Tests

“These two formulations [the traditional and alternative criteria] represent two points on a sliding scale in which the required degree of irreparable harm increases as the probability of success deceases. They are not separate tests but rather outer reaches of a single continuum.”

Save Our Sonoran, Inc. v. Flowers, 408 F.3d

1113, 1120 (9 th Cir.2005)

32

E.

Appellate Court Review Limited

A district court’s order with respect to preliminary injunctive relief is subject to limited review and will be reversed only if the district court “ abused its discretion or based its decision on an erroneous legal standard or on clearly erroneous findings of fact .” U.S. v. Peninsula Communications, Inc.

, 287 F.3d

832, 839 (9 th Cir.2002)

33

F.

Standard of Review for

Injunctions on Appeal

The appellate court’s review may be de novo under circumstances in which the district court’s ruling rests solely on a premise of law and the facts are either established or undisputed. A & M Records, Inc. V.

Napster, Inc.

, 284 F.3d 1091, 1096 (9 th Cir.2002)

However, de novo review not appropriate when district court’s order was grounded in its factual findings. See Save Our Sonoran, Inc. v. Flowers, et al. 408 F.3d 1113, 1121 (9 th Cir.2005)

34

G.

Preliminary Injunction Bond

“The district court has discretion to dispense with the security requirement, or to request mere nominal security, where requiring security would effectively deny access to judicial review.” Cal ex rel. Van De

Kamp v. Tahoe Reg’l Planning Agency, 766 F.2d

1319, 1325 (9 th Cir.1985)(finding proper the district court’s exercise of discretion in allowing environmental group to proceed without posting a bond), amended on other grounds , 775 F.2d 998.

35

H.

Preliminary Injunction Bond

(cont’d)

So long as a district court does not set such a high bond that it serves to thwart citizen actions, it does not abuse its discretion. See, e.g., Friends of the Earth, Inc. v. Brinegar ,

518 F.2d 322, 323 (9 th cir.1975)(reversing the district court’s unreasonable high bond of

$4,500,000)

V.

STATUTE OF LIMITATIONS

36

NEPA does not contain a statute of limitations. Nor does the Administrative Procedure Act (Act), 5

U.S.C. §§ 701-706, which provides for judicial review of agency actions taken under NEPA.

However, 28 U.S.C. § 2401(a) has been held to apply to actions brought under the APA. Sierra Club v. Penfold, 857 F.2d 1307, 1315 (9th Cir.1988). See also, Montana Wilderness Assoc. v. Fry , 310 F.Supp

29 (D.Montana 2004)(applying 6 year statute of limitations to a NEPA challenge)

This limitation period may be modified by other statutes.