Krugman's Chapter 26 PPT

advertisement

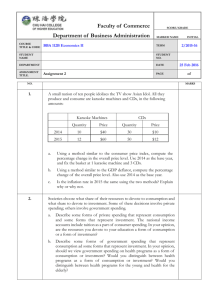

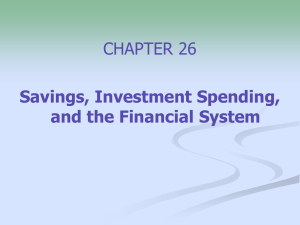

chapter: 26 >> Savings, Investment Spending, and the Financial System Krugman/Wells ©2009 Worth Publishers 1 of 58 WHAT YOU WILL LEARN IN THIS CHAPTER The relationship between savings and investment spending Aspects of the loanable funds market, which shows how savers are matched with borrowers The purpose of the five principal types of assets: stocks, bonds, loans, real estate and bank deposits How financial intermediaries help investors achieve diversification Some competing views of what determines stock prices and why stock market fluctuations can be a source of macroeconomic instability 2 of 58 Matching Up Savings and Investment Spending According to the savings–investment spending identity, savings and investment spending are always equal for the economy as a whole. The budget surplus is the difference between tax revenue and government spending when tax revenue exceeds government spending. The budget deficit is the difference between tax revenue and government spending when government spending exceeds tax revenue. 3 of 58 Matching Up Savings and Investment Spending The budget balance is the difference between tax revenue and government spending. National savings, the sum of private savings plus the budget balance, is the total amount of savings generated within the economy. Capital inflow is the net inflow of funds into a country. 4 of 58 The Savings–Investment Spending Identity In a simplified economy: Meanwhile, spending consists of either consumption spending or investment spending: (3) Total spending = Consumption spending + Investment spending Putting these together, we get: (1) Total Income = Total Spending (2) Total income = Consumption spending + Savings (4) Consumption spending + Savings = Consumption spending + Investment spending Subtract consumption spending from both sides, and we get: (5) Savings = Investment spending 5 of 58 The Savings–Investment Spending Identity In a simplified economy: GDP = C + I + G SPrivate = GDP + TR − T − C SGovernment = T − TR − G NS = SPrivate + SGovernment = (GDP + TR − T − C) + (T − TR − G) = GDP − C − G Hence, I = NS Investment spending = National savings in a closed economy 6 of 58 PITFALLS Investment versus investment spending When macroeconomists use the term investment spending, they almost always mean “spending on new physical capital.” This can be confusing, because in ordinary life we often say that someone who buys stocks or purchases an existing building is “investing.” The important point to keep in mind is that only spending that adds to the economy’s stock of physical capital is “investment spending.” In contrast, the act of purchasing an asset such as a share of stock, a bond, or existing real estate is “making an investment.” 7 of 58 The Savings–Investment Spending Identity (a) United States (b) Japan Share of GDP 25% Share of GDP 25% 20 15 10 5 0 Investmen –5 t spending –10 –15 Budget deficit Capital inflows 20 Private savings 10 15 Private savings 5 0 Savings Investmen Capital –5 t spending outflows –10 –15 Budget deficit Savings 8 of 58 The Savings–Investment Spending Identity Investment spending = National savings + Capital inflow in an open economy I = SPrivate + SGovernment + (IM − X) = NS + KI 9 of 58 PITFALLS The different kinds of capital It’s important to understand clearly the three different kinds of capital: physical capital, human capital, and financial capital. Physical capital consists of manufactured resources such as buildings and machines. Human capital is the improvement in the labor force generated by education and knowledge. Financial capital is funds from savings that are available for investment spending. So a country that has a positive capital inflow is experiencing a flow of funds into the country from abroad that can be used for investment spending. 10 of 58 FOR INQUIRING MINDS Who Enforces the Accounting? The savings–investment spending identity is a fact of accounting. By definition, savings equals investment spending for the economy as a whole. But who enforces the arithmetic? The short answer is that actual and desired investment spending aren’t always equal. Suppose that households suddenly decide to save more by spending less. The immediate effect will be that unsold goods pile up. And this increase in inventory counts as investment spending, albeit unintended. So the savings–investment spending identity still holds. Similarly, if households suddenly decide to save less and spend more, inventories will drop—and this will be counted as negative investment spending. 11 of 58 The Market for Loanable Funds The loanable funds market is a hypothetical market that examines the market outcome of the demand for funds generated by borrowers and the supply of funds provided by lenders. The interest rate is the price, calculated as a percentage of the amount borrowed, charged by the lender to a borrower for the use of their savings for one year. 12 of 58 The Market for Loanable Funds The rate of return on a project is the profit earned on the project expressed as a percentage of its cost. 13 of 58 The Demand for Loanable Funds Interest rate 12% 4 Demand for loanable funds, D 0 $150 450 Quantity of loanable funds (billions of dollars) 14 of 58 The Supply for Loanable Funds Interest rate Supply of loanable funds, S 12% 4 0 $150 450 Quantity of loanable funds (billions of dollars) 15 of 58 Equilibrium in the Loanable Funds Market Interest rate Projects with rate of return 8% or greater are funded. 12% Offers not accepted from lenders who demand interest rate of more than 8%. r* 8 Projects with rate of return less than 8% are not funded. 4 Offers accepted from lenders willing to lend at interest rate of 8% or less. 0 $300 Q* Quantity of loanable funds (billions of dollars) 16 of 58 Shifts of the Demand for Loanable Funds Factors that can cause the demand curve for loanable funds to shift include: Changes in perceived business opportunities Changes in the government’s borrowing Crowding out occurs when a government deficit drives up the interest rate and leads to reduced investment spending. 17 of 58 An Increase in the Demand for Loanable Funds Interest rate . . . leads to a rise in the equilibrium interest rate. r2 r1 An increase in the demand for loanable funds . . . Quantity of loanable funds (billions of dollars) 18 of 58 Shifts of the Supply for Loanable Funds Factors that can cause the supply of loanable funds to shift include: Changes in private savings behavior: Between 2000 and 2006 rising home prices in the United States made many homeowners feel richer, making them willing to spend more and save less This shifted the supply of loanable funds to the left. Changes in capital inflows: The U.S. has received large capital inflows in recent years, with much of the money coming from China and the Middle East. Those inflows helped fuel a big increase in residential investment spending from 2003 to 2006. As a result of the worldwide slump, those inflows began to trail off in 2008. 19 of 58 An Increase in the Supply of Loanable Funds Interest rate r1 . . . leads to a fall in the equilibrium interest rate. An increase in the supply of loanable funds . . . r2 Quantity of loanable funds (billions of dollars) 20 of 58 Inflation and Interest Rates Anything that shifts either the supply of loanable funds curve or the demand for loanable funds curve changes the interest rate. Historically, major changes in interest rates have been driven by many factors, including: changes in government policy. technological innovations that created new investment opportunities. 21 of 58 Inflation and Interest Rates However, arguably the most important factor affecting interest rates over time is changing expectations about future inflation. This shifts both the supply and the demand for loanable funds. This is the reason, for example, that interest rates today are much lower than they were in the late 1970s and early 1980s. 22 of 58 Inflation and Interest Rates Real interest rate = nominal interest rate - inflation rate In the real world neither borrowers nor lenders know what the future inflation rate will be when they make a deal. Actual loan contracts, therefore, specify a nominal interest rate rather than a real interest rate. 23 of 58 The Fisher Effect According to the Fisher effect, an increase in expected future inflation drives up the nominal interest rate, leaving the expected real interest rate unchanged. 24 of 58 The Fisher Effect Nominal interest rate S10 14% E10 D10 S0 4 E0 D0 0 Q* Quantity of loanable funds 25 of 58 ►ECONOMICS IN ACTION Changes in the U.S. Interest Rates Over Time (a) Changes in Expected Inflation and Interest Rates (b) Changes in Expected Rate of Return on Investment Spending and Interest Rates 10-Year Treasury constant maturity rate, inflation rate 10-Year Treasury constant maturity rate 7% 16% 14 6 12 10 5 8 4 6 4 3 2 1958 2008 1970 1980 1990 2000 Year 1998 2008 2000 2002 2004 2006 Year 26 of 58 The Financial System A household’s wealth is the value of its accumulated savings. A financial asset is a paper claim that entitles the buyer to future income from the seller. A physical asset is a claim on a tangible object that gives the owner the right to dispose of the object as he or she wishes. 27 of 58 The Financial System A liability is a requirement to pay income in the future. Transaction costs are the expenses of negotiating and executing a deal. Financial risk is uncertainty about future outcomes that involve financial losses and gains. 28 of 58 The Financial System (a) Typical Individual Change in individual welfare Wealth gain from gaining $1,000 (b) Wealthy Individual Change in individual welfare $1,000 $1,000 0 0 –2,000 Wealth loss from losing $1,000 Wealth gain from gaining $1,000 –1,200 Wealth loss from losing $1,000 29 of 58 Three Tasks of a Financial System Reducing transaction costs ─ the cost of making a deal. Reducing financial risk ─ uncertainty about future outcomes that involves financial gains and losses. Providing liquid assets ─ assets that can be quickly converted into cash (in contrast to illiquid assets, which can’t). 30 of 58 Three Tasks of a Financial System An individual can engage in diversification by investing in several different things so that the possible losses are independent events. An asset is liquid if it can be quickly converted into cash. An asset is illiquid if it cannot be quickly converted into cash. 31 of 58 Types of Financial Assets There are four main types of financial assets: loans bonds stocks bank deposits In addition, financial innovation has allowed the creation of a wide range of loan-backed securities. 32 of 58 Types of Financial Assets A loan is a lending agreement between a particular lender and a particular borrower. A default occurs when a borrower fails to make payments as specified by the loan or bond contract. A loan-backed security is an asset created by pooling individual loans and selling shares in that pool. 33 of 58 Financial Intermediaries A financial intermediary is an institution that transforms the funds it gathers from many individuals into financial assets. A mutual fund is a financial intermediary that creates a stock portfolio and then resells shares of this portfolio to individual investors. A pension fund is a type of mutual fund that holds assets in order to provide retirement income to its members. 34 of 58 Financial Intermediaries A life insurance company sells policies that guarantee a payment to a policyholder’s beneficiaries when the policyholder dies. A bank deposit is a claim on a bank that obliges the bank to give the depositor his or her cash when demanded. A bank is a financial intermediary that provides liquid assets in the form of bank deposits to lenders and uses those funds to finance the illiquid investments or investment spending needs of borrowers. 35 of 58 An Example of a Diversified Mutual Fund Fidelity Spartan S&P 500 Index Fund, Top Holdings (as of September 2008) Company Exxon Mobil Percent of mutual fund assets invested in a company 3.96% General Electric 2.49 Procter & Gamble 2.08 Microsoft 2.06 Johnson & Johnson 1.90 JPMorgan Chase 1.69 Chevron 1.66 AT&T 1.62 Bank of America 1.57 IBM 1.56 36 of 58 ►ECONOMICS IN ACTION Banks and the South Korean Miracle In the early 1960s, South Korea’s interest rates on deposits were very low at a time when the country was experiencing high inflation. So savers didn’t want to save by putting money in a bank, fearing that much of their purchasing power would be eroded by rising prices. Instead, they engaged in current consumption by spending their money on goods and services or on physical assets such as real estate and gold. In 1965 the South Korean government reformed the country’s banks and increased interest rates. Over the next five years the value of bank deposits increased 600% and the national savings rate more than doubled. The rejuvenated banking system made it possible for South Korean businesses to launch a great investment boom, a key element in the country’s growth surge. 37 of 58 Financial Fluctuations Financial market fluctuations can be a source of macroeconomic instability. Stock prices are determined by supply and demand as well as the desirability of competing assets, like bonds: when the interest rate rises, stock prices generally fall and vice versa. 38 of 58 Financial Fluctuations The value of a financial asset today depends on investors’ beliefs about the future value or price of the asset. If investors believe that it will be worth more in the future, they will demand more of the asset today at any given price. Consequently, today’s equilibrium price of the asset will rise. 39 of 58 Financial Fluctuations If investors believe the asset will be worth less in the future, they will demand less today at any given price. Consequently, today’s equilibrium price of the asset will fall. Today’s stock prices will change according to changes in investors’ expectations about future stock prices. 40 of 58 FOR INQUIRING MINDS How Now, Dow Jones? Financial news reports often lead with the day’s stock market action, as measured by changes in the Dow Jones Industrial Average, the S&P 500, and the NASDAQ. All three are stock market indices. Like the consumer price index, they are numbers constructed as a summary of average prices. The Dow, created by the financial analysis company Dow Jones, is an index of the prices of stock in 30 leading companies, The S&P 500 is an index of 500 companies, created by Standard and Poor’s. The NASDAQ is compiled by the National Association of Securities Dealers. The movement in an index gives investors a quick, snapshot view of how stocks from certain sectors of the economy are doing. 41 of 58 Financial Fluctuations Financial market fluctuations can be a source of macroeconomic instability. There are two principal competing views about how asset price expectations are determined. One view, which comes from traditional economic analysis, emphasizes the rational reasons why expectations should change. The other, widely held by market participants and also supported by some economists, emphasizes the irrationality of market participants. 42 of 58 Financial Fluctuations One view of how expectations are formed is the efficient markets hypothesis, which holds that the prices of financial assets embody all publicly available information. It implies that fluctuations are inherently unpredictable—they follow a random walk. 43 of 58 Irrational Markets? Many market participants and economists believe that, based on actual evidence, financial markets are not as rational as the efficient markets hypothesis claims. Such evidence includes the fact that stock price fluctuations are too great to be driven by fundamentals alone. 44 of 58 Asset Prices and Macroeconomics How do macroeconomists and policy makers deal with the fact that asset prices fluctuate a lot and that these fluctuations can have important economic effects? Should policy makers try to pop asset bubbles before they get too big? This debate covered in chapter 17. 45 of 58 ►ECONOMICS IN ACTION The Great American Housing Bubble Between 2000 and 2006, there was a huge increase in the price of houses in America. A number of economists argued that this price increase was excessive—that it was a “bubble”. Yet there were also a number of economists who argued that the rise in housing prices was completely justified. They pointed, in particular, to the fact that interest rates were unusually low in the years of rapid price increases. They argued that low interest rates combined with other factors, such as growing population, explained the surge in prices. 47 of 58 ►ECONOMICS IN ACTION The Great American Housing Bubble Alan Greenspan, the chairman of the Federal Reserve, conceded in 2005 that there might be some “froth” in the markets but denied that there was any national bubble. Unfortunately, it turned out that the skeptics were right. Greenspan himself would later concede that there had, in fact, been a huge national bubble. In 2006, as home prices began to level off, it became apparent that many buyers had held unrealistic expectations about future prices. Home prices began falling, and the demand for housing fell drastically. 48 of 58 ►ECONOMICS IN ACTION The Great American Housing Bubble New single-family houses sold (thousands) Index (2000 = 100) 220 200 1,400 180 1,200 160 140 1,000 120 800 100 600 80 2000 2008 2002 2004 2006 Year 2000 2008 2002 2004 2006 Year 49 of 58 SUMMARY 1. Investment in physical capital is necessary for long-run economic growth. So in order for an economy to grow, it must channel savings into investment spending. 2. According to the savings–investment spending identity, savings and investment spending are always equal for the economy as a whole. The government is a source of savings when it runs a positive budget balance or budget surplus; it is a source of dissavings when it runs a negative budget balance or budget deficit. In a closed economy, savings is equal to national savings, the sum of private savings plus the budget balance. In an open economy, savings is equal to national savings plus capital inflow of foreign savings. When a capital outflow, or negative capital inflow, occurs, some portion of national savings is funding investment spending in other countries. 50 of 58 SUMMARY 3. The hypothetical loanable funds market shows how loans from savers are allocated among borrowers with investment spending projects. In equilibrium, only those projects with a rate of return greater than or equal to the equilibrium interest rate will be funded. By showing how gains from trade between lenders and borrowers are maximized, the loanable funds market shows why a well functioning financial system leads to greater long-run economic growth. Government budget deficits can raise the interest rate and can lead to crowding out of investment spending. Changes in perceived business opportunities and in government borrowing shift the demand curve for loanable funds; changes in private savings and capital inflows shift the supply curve. 51 of 58 SUMMARY 4. Because neither borrowers nor lenders can know the future inflation rate, loans specify a nominal interest rate rather than a real interest rate. For a given expected future inflation rate, shifts of the demand and supply curves of loanable funds result in changes in the underlying real interest rate, leading to changes in the nominal interest rate. According to the Fisher effect, an increase in expected future inflation raises the nominal interest rate one-to-one so that the expected real interest rate remains unchanged. 52 of 58 SUMMARY 5. Households invest their current savings or wealth by purchasing assets. Assets come in the form of either a financial asset or a physical asset. A financial asset is also a liability from the point of view of its seller. There are four main types of financial assets: loans, bonds, stocks, and bank deposits. Each of them serves a different purpose in addressing the three fundamental tasks of a financial system: reducing transaction costs—the cost of making a deal; reducing financial risk—uncertainty about future outcomes that involves financial gains and losses; and providing liquid assets— assets that can be quickly converted into cash without much loss of value (in contrast to illiquid assets, which are not easily converted). 53 of 58 SUMMARY 6. Although many small and moderate-size borrowers use bank loans to fund investment spending, larger companies typically issue bonds. Bonds with a higher risk of default must typically pay a higher interest rate. Business owners reduce their risk by selling stock. Although stocks usually generate a higher return than bonds, investors typically wish to reduce their risk by engaging in diversification, owning a wide range of assets whose returns are based on unrelated, or independent, events. Most people are risk-averse. Loanbacked securities, a recent innovation, are assets created by pooling individual loans and selling shares of that pool to investors. Because they are more diversified and more liquid than individual loans, trading on financial markets like bonds, they are preferred by investors. It can be difficult, however, to assess their quality. 54 of 58 SUMMARY 7. Financial intermediaries—institutions such as mutual funds, pension funds, life insurance companies, and banks—are critical components of the financial system. Mutual funds and pension funds allow small investors to diversify, and life insurance companies reduce risk. 8. A bank allows individuals to hold liquid bank deposits that are then used to finance illiquid loans. Banks can perform this mismatch because on average only a small fraction of depositors withdraw their savings at any one time. Banks are a key ingredient of long-run economic growth. 55 of 58 SUMMARY 9. Asset market fluctuations can be a source of short-run macroeconomic instability. Asset prices are determined by supply and demand as well as by the desirability of competing assets, like bonds: when the interest rate rises, prices of stocks and physical assets such as real estate generally fall, and vice versa. Expectations drive the supply of and demand for assets: expectations of higher future prices push today’s asset prices higher, and expectations of lower future prices drive them lower. One view of how expectations are formed is the efficient markets hypothesis, which holds that the prices of assets embody all publicly available information. It implies that fluctuations are inherently unpredictable—they follow a random walk. 56 of 58 SUMMARY 10.Many market participants and economists believe that, based on actual evidence, financial markets are not as rational as the efficient markets hypothesis claims. Such evidence includes the fact that stock price fluctuations are too great to be driven by fundamentals alone. Policy makers assume neither that markets always behave rationally nor that they can outsmart them. 57 of 58 The End of Chapter 26 coming attraction: Chapter 27: Income and Expenditure 58 of 58