The Upanishadic Vision of the Human

advertisement

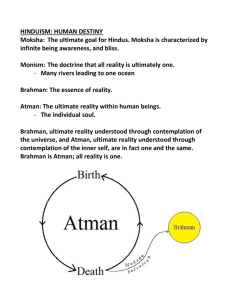

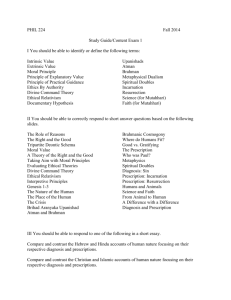

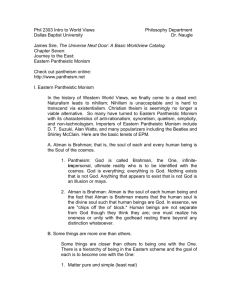

PHIL 224 The Upanishadic Vision of the Human THNs: Some Common Features As we will see, theories of human nature typically include some common elements. Identifying these elements will help us appreciate what specific theories have to offer us. Though not every theory we will consider includes specific consideration of each element, it is helpful to focus on these four. 1. 2. 3. 4. Metaphysics and Ontology: All THNs assume and/or argue for some account of the nature of reality and our specific place in it. It is these basic ‘truths’ that provide the foundation for the other elements of the theory. Crisis: Generally, THNs highlight features of reality and/or our specific nature that are less than ideal, generating problems or challenges that we need to address. Diagnosis: In the recognition of these challenges, THNs will frequently specify those dimensions of out natures that are the source of the difficulties. Prescription: On the basis of the diagnosis, THNs will typically suggest what we can do to address these difficulties. The Upanishads The Upanishads belong to what is called the Brahmanic tradition. The earliest of them date from around 800 BCE. ◦ This is far from the earliest of the textual traditions of Hinduism. Vedic literature significantly predates it. They too are compilations of earlier, mostly oral traditions. As an aside, it is interesting to note that, though the oral tradition upon which these texts is based significantly predates their consolidation in written form, this consolidation occurred within a few hundred years of the first stirrings of philosophy in Greece and China. There must have been something in the air. Brihad Aranyaka Upanishad Representing not a single authorial voice, but a disparate (in both outlook and time) one, this text is the largest (and is thought to be the oldest) of the Upanishadic texts. The text starts with a cosmogony: an account of the nature, origin, and development of the universe. The particular story we get shares quite a bit with other cosmogonies from this period. The name given to the original principle is "Atman" which here is given a material significance by the translation of the term as "body." It is also gendered (male). But this is not mere matter. For, it is immediately selfconscious, the suggestion being that self-consciousness is primary (first and fundamental). ◦ This perhaps explains why the cosmogony we get here is focused on living things rather than non-living. ◦ Notice too the role played by etymology. Atman and Brahman At the end of the creation story we find this surprising statement: "I alone am the creation, for I created all this.” This phrase highlights the ambiguity of the notion of “Atman.” Atman is both a principle of individuation and a principle of universality. ◦ Much of the disagreement between the various sects of Hinduism revolves around how to understand this ambiguity. Immediately following this, we find the introduction of the term “Brahman.” It is often used synonymously with Atman. When they are distinguished, it is usually to connect Atman to the individuated moments of the whole and Brahman with the universal. ◦ In this sense, Brahman is reality at it’s most basic, the fundamental metaphysical category. ◦ The world is at the same time one eternal and unchanging whole and a constantly changing individuated plurality. Where do Humans Fit? As you might expect, the ontology articulated in the Upanishad exhibits this same unity of unity and diversity structure. Human beings are not individuals first and part of a large whole second. The ultimate self (atman) is what it is only as part of the whole (Brahman). What we take to be our self (our ego/JivaI) is just a mask that covers over (even from ourselves) our ultimate nature as atman/brahman. The Katha Upanishad The Katha Upanishad was likely composed a some three hundred years after the Brihad Aranyaka (early 400s BCE). It is one of the most well-known of the Upanishadic texts in the non-Hindu world, perhaps because one of it’s principle themes is death and immortality. While the Brihad Aranyaka Upanishad has a primarily metaphysical and ontological significance. With the Katha Upanishad, the diagnostic and prescriptive elements become our focus. Setting the Stage Naciketas wants to know the significance of death. Going right to the source, he asks the personification of death (Yama), who, though initially reluctant, ultimately agrees to point the way to Naciketas. It’s worth noting that death’s agreement comes after a test: the temptation of worlds goods (cf. 5). ◦ This test and Naciketas’s response anticipate a fundamental distinction which becomes the focus of the second Valli. Good vs. Gratifying This distinction is the key to the Brahmanic diagnosis: the difference between the good and the gratifying. ◦ This is a very common distinction, one that is central to the diagnosis of many of the THNs that we will consider. The distinction between the good and the gratifying is mapped onto a distinction between the wise person and the fool, which in turn is coordinated to a distinction between knowledge and ignorance. In a move whose commonness is worthy of some thought, this last distinction is in turn connected to a distinction between the real self (atman/Brahman) and the ego/mask self (pp. 6-7) and ultimately to the distinction between the world of mere appearance and the 'true' world (Third Valli). The Prescription The end of the third Valli, we are given an statement of Death's lessons for Naciketas (8, 11-15). The lessons are ones that should be already familiar to us: understand that the truth of existence is “unity in diversity, diversity in unity.” The problem is that few recognize this, and are thus led astray. The solution is to come to recognize it, not just intellectually, but with the whole of our being. Failure means a return to the cycle of life for another go around and another opportunity to learn the lesson. Success means freedom from the cycle, achievement of Moksha.