"Generation Me": Narcissistic and prosocial behaviors of youth with

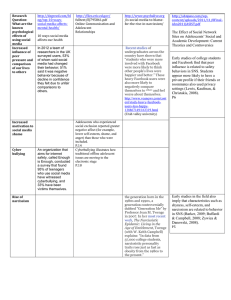

advertisement

a,b a b a Rebecca R. Carter ; Shannon M. Johnson , BA; Julie J. Exline , Ph.D ; Maria E. Pagano , Ph.D a Department of Psychology, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH ; Department of Psychiatry, Case Western Reserve / University Hospitals Case Medical Center, Cleveland, OH BACKGROUND The nation’s most commonly sought out treatment modality for substance abuse problems, Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), claims egocentrism as a root cause of addiction. Synonyms for ego-centrism in AA literature are: narcissistic behaviors, selfcenteredness, extreme self-absorption, and grandiosity. In tandem with AA’s theory, clinicians have often noted narcissistic behaviors among individuals with substance abuse problems. In Freud’s id-ego terminology, substance abuse was characterized as an oral longing and a sign of narcissistic despair (1, 2). Modern theory on narcissistic pathology and ego development describes the narcissism/addiction link as a pattern of yielding to inner urges in a way that proves costly and self-destructive (3). AA’s solution to treat the narcissistic root cause of addiction is to continually get out of self by helping others (4). MEASURES Narcissistic Behaviors The Narcissistic Personality Inventory (14) is a 40-item self-report Prosocial Behaviors. Prosocial behaviors were assessed using the five items from the General measure designed to measure subclinical individual differences in Social Survey: giving food or money to a homeless person, doing volunteer work for a charity, giving money to a charity, looking after a person’s home narcissism. The NPI has 7 subscales: authority, exhibitionism, superiority, entitlement, exploitativeness, self-sufficiency, and vanity (14). The NPI has while they are away, and carrying a stranger’s belongings (18). Items are been used with youth and adult normative populations and adult clinical rated from 1 (more than once a week) to 6 (not at all in the past year) with populations (14, 15, 16). The NPI has demonstrated good psychometric reference to the past year. The GSS has been used with national normative properties, including internal consistency (α = 0.82, 13) and test-retest samples (18). These subscale items of the GSS demonstrates adequate internal reliability (α = 0.61) and construct validity (rs = 0.07 – 0.13, 18). reliability (rs= 0.57 – 0.81, 17). Given that AA originated in 1939 and the epidemic rise of addiction in our nation’s minors, the paucity of empiricism supporting the link between elevated narcissistic behaviors and addiction in youth is surprising. One of the inherent challenges to understand this link lies between the terms ego-centrism and ego development during adolescence (5). Normative developmental processes in adolescence are characterized by heightened sensitivity, self-absorption, and preoccupation with self (6). In contrast, the defining characteristics of narcissism include a grandiose sense of self-importance, a tendency to exaggerate accomplishments and talents, and an expectation to be noticed as “special” even without appropriate achievement (7, 8). Another inherent challenge addiction research scientists face pertains to a 21st century cohort effect observed among today’s youths. This cohort effect is commonly referred to as the “Me Generation” and can be traced back to the self-esteem movement of the 1980s. Some claim that the effort to build self-confidence among adolescents has gone too far, resulting in a generation of youths who lack empathy, react aggressively to criticism and favor self-promotion over helping others (9). Addiction research involving adolescents has largely been preventive; a large body of literature identifies factors that reduce the likelihood of developing substance abuse problems. This study uses a large, representative sample of adolescents who have developed substance dependency disorder (SDD) to test AA’s theory of the link between elevated narcissistic behaviors and addiction. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS Depending on the type of variables (continuous or discrete), analysis of variance (ANOVA) or chi-square analyses were performed to examine the characteristics of the clinical sample. Random effect regression analyses were performed using a nested pair cluster to absorb pair-specific effects. Our dependent variables were two types of other-oriented behaviors: narcissistic behaviors measured with 7 NPI subscales, and prosocial behaviors measured with REFERENCES RESULTS 1. TABLE 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of ND Sample Variable Category Level Gender Male Minority 34 (30%) Ethnicity Hispanic 10 (9%) Single-parent household Yes 53 (46%) Learning disability Yes 12 (10%) Grade Less than 8 years Middle school Partial high school High School 2 (2%) 20 (17%) 88 (77%) 5 (4%) Age M (SD) 16.23 (1.71) Parental History of SDD Yes 60 (52%) History of Legal Problems No. of Arrests* (M, SD). No. of Felonies* (M, SD) History of Assault (Yes) History of Robbery (Yes) History of Burglary (Yes) Ever on Parole/Probation (Yes) Ever Jailed/Incarcerated (Yes) 2.77 (2.73) 0.53 (1.17) 34 (30%) 20 (17%) 19 (17%) 100 (87%) 77 (67%) Sexual (Yes) Physical (Yes) 30 (26%) 27 (23%) (Yes) (Yes) 28 (24%) 38 (33%) History of Abuse reported by adolescents with SDD in comparison to large scale youth surveys History of Suicide Attempts History of Self Mutilation TABLE 2. Narcissistic Personality Inventory Scores: Comparison Between Youths With and Without Substance Dependency NPI Subscale Score Total (N, %) Youths (Normative) Youths with Substance Dependency 230 (100%) 115 (50%) 115 (50%) Authority (M, SD) 4.34 (2.11) 3.87 (2.22) 4.81 (1.88)** Total (N, %) 115 (100%) 60 (52%) Race The purpose of this study is to explore narcissistic and prosocial behaviors as Entitlement (M, SD) Using a quasi-experimental design, this study compares narcissistic and prosocial behaviors of adolescents with SDD to normative controls, matched by age and 2.17 (1.54) 1.97 (1.61) 2.37 (1.43)* 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Exhibitionism (M, SD) Exploitativeness (M, SD) 2.35 (1.79) 1.85 (1.40) 1.97 (1.61) 1.50 (1.38) 2.37 (1.43)*** 2.20 (1.33)*** 7. 8. 9. Superiority (M, SD) 2.48 (1.40) 2.35 (1.42) 2.61 (1.39) 10. Self-Sufficiency (M, SD) 2.37 (1.37) 2.36 (1.52) 2.39 (1.21) Vanity (M, SD) 1.25 (1.11) 1.02 (1.12) 1.49 (1.07)** 11. 12. NOTES: * p < .05 ** p < .01 *** p < .0001 NOTES: * Assessed over the past two years METHOD To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to examine other-oriented behaviors that distinguish youths with SDD. Remarkably, most other-oriented behaviors were similar between youths with and without SDD. The other-oriented behaviors that distinguished youths with SDD were overt narcissistic behaviors and reduced monetary donations. The matched-pair design of the current study, and same decade in which all youth were interviewed, address the potential confounds of age, gender, and cohort influences to study results. Our results indicate that narcissistic and prosocial behaviors are multi-faceted constructs, certain facets of which appear related to addiction. This study was cross-sectional; therefore the significant differences found are associations rather than causations. Considering the ethical concerns of randomizing youth to develop addiction, a longitudinal within-subjects design whereby each subject serves as his/her own control is warranted to demonstrate causation. Moving out of self towards others may be particularly relevant towards adolescents with substance abuse problems. Results may inform professionals interested in youth development and youth treatment. 5 GSS items. We reported all two-tailed tests with an alpha level of p < 0.05. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1.3. OBJECTIVE collected in the past decade. DISCUSSION MEASURES Two types of other-oriented behaviors were measured: narcissistic and prosocial behaviors. 13. 14. A total of 115 substance dependent youth (14-18 years old) were enrolled in this study. Approximately half were female (48%), came from a single parent home (46%), and had a parent with a substance use disorder (52%). This sample included a considerable minority group (30%). In comparison to adolescent controls, SDD youth scored significantly higher in the areas of entitlement (F=2.37, p<.05), exhibitionism (F=2.37, p<.0001), exploitativeness (F=2.20, p<.0001), and vanity (F=1.49, p<.001). 15. 16. gender. This design was selected over the standard randomized, controlled field 17. experiment design given the ethical issues of assigning adolescents to a disease condition. Comparison groups were matched with identified relevant variables; prosocial behaviors have been known to increase with age while gender differences in prosocial behaviors have also been well documented (10, 11). Thus, each adolescent with SDD was matched to a youth control by age and gender. Inclusion criteria for the clinical sample included: possessing stable contact information, being between the ages of 14 and 18, meeting DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for substance dependency, and being medically detoxified. Exclusion criteria included: being illiterate, having major chronic health problems requiring hospitalization, and being suicidal or homicidal. For youth controls, two survey samples were selected. Detailed information regarding the research designs of the two survey samples selected as normative controls is explicated elsewhere (12, 13). The TABLE 3. General Social Survey Scores: Comparison Between Youths With and Without Substance Dependency General Social Survey (GSS) Item Youths (Normative) N=131 Youths with Substance Dependency (N=115) Gives money to charity (M, SD) 4.66 (1.31) 5.06 (1.15)*** Gives food/money to homeless (M, SD) 4.45 (1.44) 4.80 (1.17)*** Looks after neighbor’s plants/mail/pets (M, SD) 4.88 (1.33) 4.67 (1.36) Volunteers (M, SD) 4.98 (1.34) 4.84 (1.38) Carries belongings for stranger (M, SD) 4.95 (1.23) 4.46 (1.20)* GSS Total Score 23.93 (3.98) 23.82 (4.30) NOTES: *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .0001 GSS items are rated: 1= “more than once a week”, 2= “once a week”, 3= “once a month”; 4= “2-3 times in past year”, 5= “once in past year”; 6= “not at all”. current study was approved by the University Hospitals/Case Medical Center Institutional Review Board. b When GSS items were compared for addicted youth and non-addicted youth, adolescents with SDD were less likely to give money to charity (F=5.06, p<.0001) or give to the homeless (F=4.80, p<.0001) in comparison to adolescent controls. 18. Abraham K. (1908). The Psychological Relations between sexuality and alcoholism. In (1973), Selected Papers on Psychoanalysis. London: Hogarth Press. Freud, Sigmund. (1887-1904). The Complete Letters of Sigmund Freud to Wilhelm Fliess. Translated and edited by Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson (1985). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Baumeister, R. F., & Vohs, K. D. (2001). Narcissism as addiction to esteem. Psychological Inquiry, 12, 206–210. Zemore S.E.,& Pagano M.E. (2007). Kickbacks from helping others: Health and recovery. In: Galanter M, Kaskutas L, editors. Recent developments in alcoholism. Vol. 10. New York: Plenum. Keagan, R. (1982). The Evolving Self: Problem and Process in Human Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Youniss, J., & Smollar, J. (1990). Self through relationship development. In H. Bosma & S. Jackson (Eds.), Coping and self-concept in adolescence (pp.129-148). Berlin: Springer Verlag. Kohut, H. (1971). The Analysis of the Self. New York: Int. Univ. Press. Millon, T. (1990). The disorders of personality. In L.A. Pervin (Ed.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 339-390). New York: Guilford Press. Twenge, J. M. (2006). Generation Me: Why today’s young Americans are more confident, assertive, entitled—and more miserable than ever before. New York: Free Press. Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women's development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. McAdams, D. P., Hart, H. M., & Maruna, S. (1998). The anatomy of generativity. In D. P. McAdams & E. de St. Aubin (Eds.), Generativity and adult development: How and why we care for the next generation (pp. 7–44). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Davis, J A., Tom W. S., and Marsden, P.V. (2003). General social surveys, 1972–2002 (cumulative file, computer file). 2nd ICPSR version. Chicago, IL: National Opinion Research Center (producer); Storrs, CT: Roper Center for Public Opinion Research, University of Connecticut; and Ann Arbor, MI: Interuniversity Consortium for Political and Social Research (distributors). Exline, J. J., Baumeister, R. F., Bushman, B. J., Campbell, W. K., & Finkel, E. J. (2004). Too proud to let go: Narcissistic entitlement as a barrier to forgiveness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87, 894–912. Raskin, R., & Terry, H. (1988). A principal-components analysis of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory and further evidence of its construct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 890-902. Prifitera, A., & Ryan, J. J. (1984). Validity of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI) in a psychiatric sample. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 40, 140-142. Shulman, D. G., McCarthy, E.C., & Ferguson, G.R. (1988). The projective assessment of narcissism: Development, reliability, and validity of the N-P. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 5(3), 285-297. del Rosario, P. M., & White, R. M. (2005). The Narcissistic Personality Inventory: Test-retest stability and internal consistency. Personality and Individual Differences, 39, 1075-1081. Smith, T.W. (2005). Altruism and Empathy in America: Trends and Correlates. Retrieved September, 1, 2009, from http:// http://www.norc.uchicago.edu/NR/rdonlyres/7EFE80C6FD3A46F7-AF22-ACE5C9E34E14/0/ AltruismandEmpathyinAmerica.pdf. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This study was supported in part by a grant award (K01 AA015137) from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) and a grant award (#13591) from the John Templeton Foundation to Dr. Pagano. The authors thank New Directions, an adolescent residential treatment facility in Ohio, for their assistance in the data collection. Analysis and poster preparation were supported by the Department of Psychiatry, Division of Child Psychiatry, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH. The authors and presenters report no other financial support or affiliations to disclose.